Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Milton Henry

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Milton Henry

Interview: Milton Henry

"Hopefully we can leave a legacy for the young to continue"

Sampler

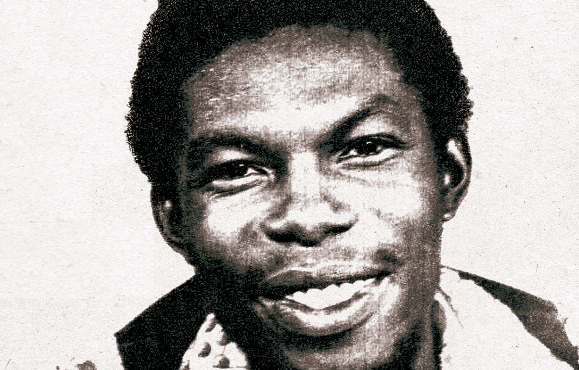

The history of reggae music has many participants whose level of commercial success doesn't always reflect their importance. Take the wide-ranging-voiced singer, guitarist and arranger Milton Henry: who despite moving and grooving with some of the biggest names in Kingston during the 70s did not record a solo album until the early 80s when he had put down roots in New York.

Aston “Milton” Henry was born on January 19th 1950 in Allman Town, central Kingston – the fifth of seven children. His father, a carpenter, and his mother, an office worker, came out of St Ann Parish, birthplace of Bob Marley and Burning Spear.

Milton’s guitar playing attracted the interest of future Freedom Sounds producer Bertram Brown and the singer Carl Dawkins – for whom Henry arranged the 1969 Jamaican hit Satisfaction. He had a role in a string of harmony groups: the Techniques, the Leaders, the Progressions, and the Emotions. At the start of the 70s he recorded for Lee Scratch Perry as King Medious before reverting to his own name and scoring with a 1976 cover of the Impressions Gypsy Woman on Rupie Edwards aptly named Success imprint.

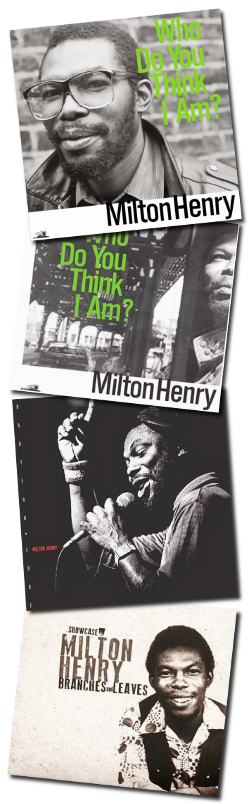

By that year Milton had relocated to New York where he would become a key staff member at Lloyd Barnes’ famed outpost Wackies. There he cut his first LP Who Do You Think I Am (1985) followed by a second, Babylon Loot, (1987) for the Japanese Tachylon label.

Angus Taylor conducted this interview in 2013 when researching the liner notes for Milton's lengthily awaited third album Branches and Leaves. Produced by Spanish studio maestro Roberto Sanchez and released on France's Iroko records, it introduced Henry's velvet voice and sagacious lyrics to a new generation - while letting his long term fans commune with him again.

Your mother sang in church. Would you say that that’s where your gift for singing came from?

Yes, she was a singer. She wasn’t on the choir but she sang in church. It’s her - the singing kind of came from her because I listened to her singing. She had this wonderful voice. I started singing but when she realised that I took it so seriously I noticed that she had kind of stopped – she held back. Even watching me all those years and she always said “Oh man, you ain’t got to the right people yet”. After so many years she thought I would have made it to a certain status but she doesn’t know the politics that’s involved.

You attended the famous Mico Practising School –- along with Horace Andy and several other future reggae artists.

I first attended Allman Town Junior School and then the Mico Practising School that took me in to elementary level up almost to high school level. Horace Andy, Augustus Pablo and Willie Stewart who was the drummer from Third World, all the guys were going there and it became a revolution. Olive Lewin was one of the music teachers there, her plus a few others but she became the most successful.

My mother had this wonderful voice

My mother had this wonderful voice

So that’s where you furthered your musical education?

Yeah, when I was at Mico. Because they train you there, we got up into choral singing and the musical curriculum was strong. There was another teacher by the name of Pinnock, she was very good as a choir master for the school. Olive Lewin was basically from the college, because there’s also a college on the grounds and they have the elementary school attached. It was one compound. This is where they’d train teachers, a teachers college, that’s actually what the whole foundation of that school was based on. But we were lucky guys, we were like the guinea pigs for the students where they’d learn and they’d come and do exercises, like an intern. It was interesting though that school, a lot of successful people got out of there.

Who were some of the other people that came through there?

Tony Gregory came out of there. Did you ever hear about that singer? Oh yeah, he was a little bit before I was but Tony Gregory he’s a badman. He’s serious. If you go and check that man, he’s highly in that field too. I think the Tuckers, Jimmy Tucker was there. These were guys who got to there before me who were singers. Jimmy’s family, the same Tucker family, they came out of Mico too. I’m only speaking for the musical stance. I’m sure a lot of guys have done well and have become leaders in the sports arena, and administration and whatever. It was a pretty good school to move on to higher education as well.

Your father, being a carpenter, wanted you to learn a trade instead of music?

He started me out in electronics because they soon realised that I didn’t like the carpentry thing and cabinetmaking. But it was already in the family too because my older brother was a carpenter and cabinetmaker. I didn’t like seeing my father doing his own business and how people treated him, I didn’t want that because that’s too much, man. You work and you finish your work and you don’t get paid. I tried to rebel and he didn’t really want to help me with the music - it was my mom who helped me with the music. For that reason I had to do home study courses to decide what I wanted, because I was running with a lot of Alpha Boys School fellows too and they knew the music and they would pass along a little information here and there.

I didn't like seeing my father doing his own business and how people treated him

I didn't like seeing my father doing his own business and how people treated him

Who were you running with from Alpha School?

There was one fellow by the name of Hopeton Elliot, he became a bandleader. Wade Williams who plays drums, another cat from Alpha from the earlier days, there was another saxophone player, a few other fellows.

Even though your father wasn’t sympathetic to music your brother gave you your first guitar.

Oh yes! He made guitars, flutes and piccolos and stuff. He made guitars, so I had my guitar. At the age of thirteen I started playing around with it.

How did you enter the business in the second half of the 60s? This was kind of rocksteady time, wasn’t it?

Yeah. Funnily enough as I was playing around with the guitar in the neighbourhood there were a few cats who I actually grew up in Allman Town with. There was Carl Dawkins, I was around with Rudy Mills, another cat by the name of Tony Russell, Patrick Hardy. How I really got started was there were some cats, they heard about me being in Allman Town but they did not come from Allman Town. These were Bertram Brown, a guy named Peter, and Keith Blake which is Prince Alla. They were going to school on the east side so they had to pass through the town where I was and somehow they checked me out and we kind of started a musical collaboration there.

So you started rehearsing with them, around 1966 time, out west in Greenwich Town. How did you first start recording?

It was Carl Dawkins who got me to do one of my first recordings with JJ Records but it was never released. The first official release of me and Prince Alla, we were on Joe Gibbs’ first session, with Errol Dunkley and Roy Shirley, but that was his first session.

This was The Leaders’ Hope Some Day, the B-side to Stranger and Gladdy’s Just Like A River, released on Gibbs’ Amalgamated imprint in 1968?

We got a couple of hits out of the session, we got Be Good from Roy Shirley, Hold Them, and he got You’re Gonna Need Me from Dunkley on that session. But me and Prince Alla were down as The Leaders, that was my first professional recording.

Myself and Prince Alla, we kind of set the tone for all those cats in Greenwich Town

Myself and Prince Alla, we kind of set the tone for all those cats in Greenwich Town

The Leaders, was yourself, Prince Alla and Roy “Soft” Palmer. Tell me about “Soft” Palmer – did he have any connection to the Palmer Brothers?

Yeah, the connection was the other brother, which was the younger brother, I think his name was Frankie. He had made some recordings but I don’t think he had called himself Frankie Palmer. That Palmer group, I think Soft was a part of, they probably started recording after I left that circle because I actually saw the work they were doing. But I know that they were working because, myself and Prince Alla, we kind of set the tone for all those cats in Greenwich Town. There were a few other guys down there in Greenwich Town who were doing good.

At the same time as you were making links in the west you were still hanging with musicians in Allman Town?

I went all the way from the east and central part of Kingston to the west to work with Keith but during the time while I was in Allman Town, me and Carl Dawkins, that’s where the music really started from. I was arranging for him, helping him with his arrangements and doing his rehearsals for him, setting the mechanical makeup of his work. I was doing the same thing with the Techniques too during the time when Junior Menz was in the group and Bruce Ruffin. The time where Pat Kelly really wasn’t in the group. Pat came after. I was kind of quite related to Mr… what do you call this guy’s name, the fat man down there on Bond Street?

Duke Reid?

Mr Reid. I got a little experience being around him too. He did some recording with me which was never released…

Duke Reid did some recording with me which was never released

Duke Reid did some recording with me which was never released

When did you voice those unreleased recordings with Duke Reid?

That was with the Techniques around that time Love Is (Not) A Gamble and all those songs were being done because I was the one who was rehearsing the Techniques at the time. But Carl Dawkins, I helped him to arrange. This was after Baby I Love You where I wasn’t around, he was on his own, he was doing well. But I helped him to arrange his Satisfaction tune because we were actually moving together. It came out to be one of his biggest songs. I made up a chord structure and suchlike for him. He was distraught when I left and moved to the west with those fellows, Prince Alla and whatnot, but I had to try to find my own career. When I came back into the town I had The Progressions working, I was multitasking.

Who was in The Progressions? What was your role?

I was the musician, doing arrangements and vocals with them. It was me, Patrick Hardy, and Tony Russell. There was Audley Rollen, we tried him in but he didn’t make the cut. Rudy Mills was also in and after a while his career kind of took a turn because he was with Derek Harriot and he started getting a few hits. It was the same group that was at Studio One by name of The Jets. We had Derek Bucknor and a few other guys, as Rudy Mills and The Jets.

I was the musician, doing arrangements and vocals with them. It was me, Patrick Hardy, and Tony Russell. There was Audley Rollen, we tried him in but he didn’t make the cut. Rudy Mills was also in and after a while his career kind of took a turn because he was with Derek Harriot and he started getting a few hits. It was the same group that was at Studio One by name of The Jets. We had Derek Bucknor and a few other guys, as Rudy Mills and The Jets.

By the time of The Progressions – 1968 - rocksteady had progressed to reggae.

The album that me and The Progressions did was about ’68, ’69, so that was about three years later reggae was kind of taking over. I did [the 1970 Pama LP] Reggae To UK With Love, we kind of put that together, me and The Progressions. That particular album is all cut up on Trojan, on some of Trojan’s boxsets. By this time myself and The Progressions, we were doing our own recording, we started recording some of the local cats around. So we were recording Freddie McKay, we recorded a couple of other guys who are not so recognisable, and The Emotions, we had recorded them too during that time.

As the 60s became the 70s you started to work with The Emotions – the group whose alumni included Max Romeo and Robbie Shakespeare’s brother, Lloyd.

Yeah but I came later. It was Brenton Joseph, Leroy Turner and Lloyd Shakespeare that were The Emotions because that was right after Max Romeo had left the group.

This was about 1970?

Yeah, we were there. That’s when the Hippy Boys came into prominence. When I went there we came up with the hit which was the Dr No Go thing with Hippy Boys - that was [on the same rhythm as] The Emotions – You Can’t Stop Me. Have you ever heard that You Can’t Stop Me, Dr No Go? The track became the number one song Dr No Go, which was Gay Feet.

I was one of the first members in the Hippy Boys

I was one of the first members in the Hippy Boys

And that was for Mrs Pottinger?

Yeah, and that’s how the Hippy Boys came about. I was one of the first members in the Hippy Boys, so was like Carlton Barrett and his brother and even after that you had a couple of drummers because they moved onto other things. The guy who started Hippy Boys was a cabinetmaker who was a musician by the name of Webby. Did you ever see that guitar that Peter Tosh had that was shaped like a gun? I think it might have been Webby who made that. (laughs) These guys, these cabinetmakers were skilled at making their own instruments.

So you were working with The Progressions, The Emotions, the Hippy Boys – were you always doing lots of projects at the same time? Did you always have more than one thing on the go?

Yeah generally. Because of how demand was so I actually wound up doing more than one project at a time.

How did you decide to come and work with Lee Scratch Perry in 1969?

You know what happened? Something terrible had happened in The Emotions and that was suggested to make some extra funds so that we could support the group. Lloyd Shakespeare had run into trouble with the law and he had been taken from the group, so that’s when we brought Audley Rollen into The Emotions, while Lloyd was away. We moved The Emotions from Pottinger to Lloyd Matador, we did a series of songs there with Audley Rollen. And so I stepped off and did this audition and got to do this recording with Scratch and he liked what I was doing. That’s how I wind up at Scratch.

No Bread and Butter was Tubbys' favourite song... U-Roy was hitting it so hard, man!

No Bread and Butter was Tubbys' favourite song... U-Roy was hitting it so hard, man!

This is when you recorded your first single for Scratch as Milton Morris.

The first single which was written by Tony Russell, named No Bread And Butter, that was for Scratch – the first recording was a hit. Released it and it went over during those years. It wasn’t a big national hit but it was one of the good vibes in the dancehall. It was Tubbys’ favourite song. I remember when my boys used to come back and tell me that U-Roy was hitting it so hard, man! My boys around me, they were kind of proud of me, knowing that I was in their clique and doing such great things.

Why did you record as Milton Morris?

It’s supposed to be Milton Henry but Scratch used to make that mistake, and that’s what he put out on the record. He had to correct it. It came out as Milton Morris and it was not. These guys, they weren’t so clean about how they do business, in the sense of the information back then didn’t mean much to them, as much as getting the record on the turntable. It didn’t mean much to them when it comes to information and then after years now they’re realising that the industry is taking off and they’re going to start taking caution about how they do things. While some people were not as reckless, they weren’t always meticulous about how they represented their work, you know? Or presented, in that sense. When I did a second song for Scratch I realised that Scratch wasn’t so forthcoming. Because during that time I had to go up into the hills, man, right when I did This World.

And This World was a hit, right?

Yeah, This World was a hit. That was a big hit, and yet they tried to ban it. They didn’t want to open it up much but then I came to realise that that was a song about equality and justice for both man and woman, when it’s showing that man and woman should have equal representation.

This World was a big hit, and yet they tried to ban it

This World was a big hit, and yet they tried to ban it

Why did you record that song under a different name – King Medious?

Because I was in The Emotions at the time and it was just something to make some extra money. That’s why I used that name. The name was revealed to me through a divine study that I was doing, that was just before I went up into the mountains. That divine study led me to that revelation of that name - King Medious, so I used it.

Why did you decide to leave Scratch?

Well, I was there when Bob and the whole bunch of them were there – all of us - and I’m noticing that preferences were going on. I would have wanted to do an album but the support was not coming from Scratch and for that reason I didn’t want to get tied up. I try not to get myself caught up like that. Serious cuthroat business, man. So I backed out, I backed off of Scratch, with all that was going on there.

How were you doing financially at this time?

It felt comfortable growing up in Kingston during those years even though it was a little tough for most. I wasn’t really having too much hard times, yet now I knew I still had to have support to be able to do the music, so I had to go to work. So after a while I went into the postal department to hold me down a day job because I started making family.

I tried to start a little business, me and my sister we started a little business – we opened a record store with my brother-in-law, the three of us. I had it on the west-side in the Three Mile area for a while and then I left it and went off to the postal office. They were mismanaging the money and I was the one who was actually bringing in the goods a lot. You know how when you have an influence in that industry and you can get people to probably trust you or to get consignments easier than others. They used that but my brother-in-law wasn’t actually forthcoming that much. Eventually we did some recording together, me and my brother-in-law during that time. A lot of things happened during that time. The label that we were using to begin with was Kismet, it was a label coming from The Progressions. We were releasing some songs on Kismet. I’m looking for a particular song I’ve forgotten the name of the label but I understand we had a label too, but there’s a song named Politics & Babylon, the singer’s name is Paul Kelly. I’ve not been able to find it.

I was also recording another artist by the name of Michael Anthony. That came about because I had to piggyback with him. We did a song named Sin A Man which was on our own label by the name of The Archer. That had to be early 70s – like ’74 or ’75.

How did you decide to cover the Impressions Gypsy Woman in 1975?

That was the time I was getting a little frustrated with what was going on with Progressions because we were recording a bunch of artists and we realised that all the money got screwed around because Pama wasn’t paying us for the album [Reggae To UK With Love] after that album was being sold. So I went to the post office and I took some of my own money and recorded Gypsy Woman.

You licensed that to Rupie Edwards, is that right?

Yeah I did. I gave him the distribution.

So after Gypsy Woman came out in ’76 you went to the States?

In the same year, ’76. I should have come to London if I’d known the song was taking off over there! (laughs) But I’d just gotten my little vacation from the post office and I went.

So your family had migrated to the States?

Yeah they had migrated there. In the 60s. Like ’69. So I came and then I brought my immediate family.

Did you go back and forth after you went over in ’76? What were you doing for a living? Were you in the record business?

I went back and forth. Yeah, I was in the record business. I started out running a couple of stores up here in New York from the salesman standpoint. I was doing record sales.

So, being a salesman, that’s how you met Lloyd Barnes of Wackies?

Yeah, actually we met when I was putting out a version of Gypsy Woman and we met in the mastering, when we were doing the mastering for the samplers. It took off from there. Before that I was doing sales in Brooklyn at one of the major stores. That’s how I met him throughout that time and he told me what he was doing. I was living in Jersey too. Then I noticed what he was doing and we kind of took it from there. Me and him got into this collaboration and I was helping him run his little business.

You were helping him behind the scenes. How did that relationship change to you actually getting into the voicing booth and recording?

They kind of realised that I was a singer but I never chased, I never ran after it, you know? Because I was always thinking about the big picture - being someone like Mr Dodd and I guess Bullwackie had the same dream, you know? We were looking at later down the road as we established our dreams. That was the pitch, even since I was in Jamaica. You want to do something that’s not just average, none of us wants to be an average Joe.

I was always thinking about the big picture - being someone like Mr Dodd

I was always thinking about the big picture - being someone like Mr Dodd

So I was there operating with them until they took on so much. When I got into the studio I only wound up doing two albums, where I could have probably done three or four or five, but I just had to help with the administration because a lot of things were not in order. For it to be in order somebody had to be there who would be able to spend the time to make sure that things were in place. I was working with a great little English man who helped to catapult Wackies to the place where it first really started getting recognition. He was a graphic artist by the name of Edward Brennan. I always consider him to be a very important part in raising the awareness of what was happening with Wackies. I met up with him just when I had to come to London to give Rae the assistance… because Rae was very strong part of Wackies too during those times and helped to really make it what it is.

Rae Cheddie – I know him here in London!

He’s a serious dude. That’s one of my aces. He was the Wackies European link. He got all the stuff to distribute there. He’s the one who introduced me to Ed Brennan but Ed Brennan really played a good part in helping too.

You also voiced a couple of tunes that were released by your own friend Bertram Brown around 1978-79.

You see those recordings? By the time I was able, myself and Chinna had got into a collaboration and Chinna had given me some work to do. So by that time I was in the States at Wackies. But that work with Bertram Brown was the same work, some recordings that Chinna had passed on for me to do vocals and arrangements on. I did the vocals and arrangements here in New York and released it back in Jamaica through Bertram Brown.

How did you come to record your first album Who Do You Think I Am?

The first album took nearly two years to do. That was slowly put together, you know? It was a project that came whenever I got a chance from the business I would go and really probably lay a track down. The reason why I did not jump right in was because the sound that Wackies had in the studio to me didn’t have that vitals we had in Jamaica, so it was in development. He started out with two tracks, man. Then he progressed to a four-track, then he moved to an eight-track and so forth and so on. I watched it grow. Right now we’re in the state of the art digital analogue studios but it was a struggle to get and it’s still a struggle because they have not made any money yet out of the Wackies thing. But we try to keep business going and secure it as much as we can. Hopefully we can leave a legacy for the young to be able to continue.

The first album took nearly two years to do. That was slowly put together, you know? It was a project that came whenever I got a chance from the business I would go and really probably lay a track down. The reason why I did not jump right in was because the sound that Wackies had in the studio to me didn’t have that vitals we had in Jamaica, so it was in development. He started out with two tracks, man. Then he progressed to a four-track, then he moved to an eight-track and so forth and so on. I watched it grow. Right now we’re in the state of the art digital analogue studios but it was a struggle to get and it’s still a struggle because they have not made any money yet out of the Wackies thing. But we try to keep business going and secure it as much as we can. Hopefully we can leave a legacy for the young to be able to continue.

So when did it go from two-track to four-track to eight-track?

Like from the early 70s it was two-track. The reason being they were getting tracks from Jamaica and doing overdubs and stuff, fixing them up and releasing them. Some of the early Wackies releases were also done in Jamaica while some were being done here [in New York]. Wackies had started doing that before I actually met him in ’76, so he probably started about ’73, ’74 doing recordings, he and a fellow named Munchie.

Munchie Jackson.

Munchie Jackson, there you go, yeah. So early years Munchie Jackson and Tony Jackson and Lloyd and a few other guys, a fellow named Morgan, they were also the Trojan brothers from early too. This is what happened. So after I got there things started improving more and more and he moved to the four-track. He had a sound system too, but it was when he was up on White Plains Road he moved to that four-track.

Which year did you start recording the first album and when did you finish?

That was like ’82, ’83 or maybe ‘84. That album took a little while because some of the tracks were coming on in Jamaica. Because we were in collaboration with Sugar Minott as well -helping in the operations and the administration and whatever was going on with Black Roots. Because that’s the strength… we were giving and they were giving us to Sugar Minott who played an integral part in what Wackies was doing too at that time. So it started being made likely about ’82.

Sugar Minott played an integral part in what Wackies was doing

Sugar Minott played an integral part in what Wackies was doing

And what about the second album – Babylon Loot?

The second album, that was done in too much of a hurry. The Japanese had gotten involved by then and I didn’t feel comfortable about the album, the way it was being rushed into and they rushed the mix and everything. That’s why the album is not as potent as the first album. Because then the music started changing and they were using all the electronic devices and all these things into these recordings. So it was really released in Japan because by this time we were going to Japan. Max Romeo and a few other artists, Sugar and all them, they were travelling and stuff. They were hustling… honestly I feel they were hustling the Japanese but the Japanese were smart people, they were learning as much as they could learn from the reggae and after a while they knew what they wanted to do and kept doing their thing after that. The album is ok, but me as a musician and everything, I wasn’t happy, I wasn’t totally happy with it. I said it was premature.

What were you doing in the 1990s, recording-wise and music-wise, leading up to the 2000s when you started collaborating with Roberto Sanchez?

I started doing some work for The Meditations, I started doing a road tour with them. I toured with them for a good while, I did a good stint. That was about ’95 I started out with them.

Somebody played me what Roberto was doing and I said "He's something else, ain't he?"

Somebody played me what Roberto was doing and I said "He's something else, ain't he?"

What did you do between the second album coming out and ’95? How were you surviving?

I wasn’t doing anything besides working with the local thing and after ’95 while I was on tour with The Meditations. I started doing another album for a production, which the album had only reached pre-release and was never released. With a company called Tello Entertainment. The album was completed in 2007 and the market was so bad, the man didn’t want to release it. You know, that’s when the market was shot, around that time. 2006 and 2007, those were some bad years for the industry because of all of the downloads and whatever. The guy got scared and he didn’t want to, so he held me up on that and I was contracted to him. So it held me back and I did not release anything since that time until I started to collaborate with Roberto.

How did you get in contact with Roberto?

Roberto hit me up through the social media MySpace a few years back. I have a San Diego house and I went out there a few years ago and I told them about Roberto Sanchez because it’s a Mexican-American community! Then somebody played some stuff for me that Roberto was doing and I said “Wow! This guy is not easy to describe. He’s something else, ain’t he?” because he was getting the kind of sound that he was getting.

So over the years we talked and we decided to collaborate and the rest is what we have right now. It’s not so much about a whole bunch of money because you know, these are little independent companies, they’re independent like myself. So in my case I support the indies because the big industrials they crush, they crush you, man. And when you get your stuff tied up with them and you can’t get paid, in the way that some of the other producers would take your product. So I have been struggling with independent producers for years. I’m just keeping it real and supporting the independent producers. It’s not so much about the money but about the preservation of the music, for me.

It's not so much about the money but about the preservation of the music

It's not so much about the money but about the preservation of the music

Tell me a bit about how you wrote the songs for the album. Did you have them all ready, did you write them for the project?

A couple of the songs like me and my wife wrote. One or two of them, we have another co-writer. One that I love, Let Go The Ego I just had the title. A friend recommended the title and I just do the rest. I’d go away to a little seaport town so I could write and finish up writing just Hold My Hands and Rastafari Cannot Die, songs like those.

Who’s the co-writer?

He’s the same cat who wrote Satisfaction for Carl Dawkins. His name is Roland Grant. He’s been a long-standing friend of mine, so we still collaborate. He’s here in New York. I co-wrote with him: Rastaman Beware and Crisis, we both collaborated on that lyrically. Most of the rest of it I just come up with, except for the title from my friend Anthony Chimming for Let Go The Ego. The rest me and my wife came up with ideas, so that’s how those lyrics come about. Some of them seem to kind of come on very strong. So I’m just hoping I’ll be able to get some good songwriter’s credit because over the years I have not got any real credit for being a songwriter.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2024 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z