Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

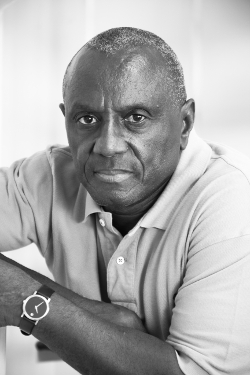

Interview: Augustus ''Gussie'' Clarke

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Augustus ''Gussie'' Clarke

Interview: Augustus ''Gussie'' Clarke

"Put the project first and money will come after"

Sampler

Augustus “Gussie” Clarke is one of Jamaica’s select class of mega-producers who continued making hits from the 70s analogue period through the 80s digital era and beyond. The category includes Lloyd “Jammy” James, Donovan Germain and, were it not for his tragic murder, probably Osbourne “King Tubby” Ruddock too.

Gussie was orphaned at a young age and raised by his adoptive mother on Church Street in downtown Kingston. While other children were running and playing, Gussie was hiring out the use of his bike to buy the constituent parts for a sound system. He could call himself a sound man and fledgling producer by the time he was 18.

He made a name for himself in the deejay wave of the early 70s via sides using U Roy, I Roy and Big Youth on his various Gussie labels. But Clarke also had a fruitful association with singers – notably the Mighty Diamonds and Gregory Isaacs – who he continued working with in the 80s. Voicing these veterans and new toasters like Shabba Ranks, Gussie would create some of the outstanding productions of the digital boom. They emanated from his Music Works studio on Slipe Road, next door to his friend and rival Germain.

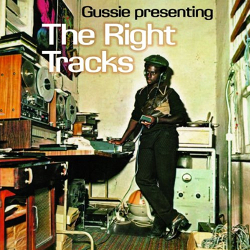

Never one to rest on past successes, he moved from Music Works to Anchor Studio in 1993 which is still a recording hotbed to this day. In 2014 he released what promises to the first of three anthologies for VP Records: the Right Tracks – an extended reissue of a 1976 compilation focusing on his early work.

You might think that a music mogul who grew up downtown around the sound system scene would be a gruff and gritty character. Instead the man who answers the phone is a high voiced, suave sounding individual. His demeanour is remarkably similar to that of Curtis Lynch – the younger English producer who calls Gussie his mentor – and was given unprecedented access to Music Works rhythms for Lynch’s 2013 project Gregory Isaacs Remixed. Angus Taylor got a strict half an hour with Mr Clarke to shoot the breeze on a variety of topics. This is what was said.

Where in Jamaica were you born?

I was born in Clermont, St Mary. I have no knowledge of it because I left pretty early and came to downtown Kingston. 81 and a half Church Street. That’s actually where the picture featured on The Right Tracks is from. Upstairs in our house we had a little home studio there. In those days you bought your TEAC or Tascam multi track machine and all that stuff.

You didn’t know your biological mother. Where do you think you get your entrepreneurial spirit from?

To be quite frank, I can’t say. I’ve always been and still am a person who is always trying to look the next step ahead, never be complacent, try to be different. I live by certain philosophies that anybody can do what you and I can do, but if we do it differently the difference is what will make success or failure. I’m always thinking outside of the box so usually when things change I am never caught sleeping. I am one of the five wise virgins who had oils in their lamp all the while. That’s just how I’m made up.

I’m always thinking outside of the box so when things change I am never caught sleeping

I’m always thinking outside of the box so when things change I am never caught sleeping

What was your first experience of music?

My first experience of music was living downtown and hearing the sound system play. I was captivated by the music. I decided to make a little sound system myself called King Gussie’s Hi Fi.

You attended Kingston College along with several notable future producers. Which subjects did you enjoy?

Maths was never one. I liked literature. I liked language. And I kind of liked French. I was kind of a hands on guy really so I liked woodwork and that’s where I learned to make speaker boxes and all that.

Tell me about making your sound.

It was very small and I made the boxes at woodwork classes at KC, got speakers and put them in and that’s where it started. Prior to that I had saved up lunch money to buy a transistor amplifier. I started the sound and swapped the transistor amplifier for a tube amplifier made by a technician. I swapped the tube amplifier for a rhythm with Errol Dunkley who needed an amp for his record store, cut that rhythm with U Roy who voiced a song and that’s where it all began.

But in between there were other transitional points. For example I used to import foreign records from the States to sell to all the sound systems in Jamaica so I had all those connections. And also at a point when I evolved in the business I would export records to stores like Hawkeye in the UK and Keith in the US so at different times different transitions happened.

You anticipated my next question – there was the sound, the record imports and the dub cutting. In what order did these fall into place for you?

First of all it fell into place with the sound system. During the process of the sound system we started to import records and sell them to the local sound systems of the day. Within that process I bought a dub machine from Duke Reid and started cutting dubs upstairs which is where you see that profile picture on The Right Tracks. Within all of that we had this great connection to everybody so we started to export records to the UK and the US primarily. That was kind of the order of things until we moved on to swapping the tube amplifier for a cut of the rhythm Baby I Love You from Errol Dunkley and voicing U Roy on that rhythm.

Is it true that you grew up around Big Youth?

Yeah we were kind of in the same community. He was playing on Tippertone sound. He was at Princess Street and I was on Beeston Street where the sound system was. So we were in the same proximity.

You were quite young when you entered the sound system business. The sound business has a reputation for being quite rough. Did you have to steel your nerves?

I was kind of on the peripheral of it. I was kind of this little kid that everybody liked. I wasn’t a bad kid. I didn’t give trouble. So I got along with everybody. But I wasn’t actually in the sound thing because the sound I had was a little one that had its limitations in where it could play. We were not really exposed to where the great big Tippertones would be playing, for example, so we had a limited interaction at that level. But the greatest part of the interaction was I was importing records into the island that they wanted to buy, I was cutting dubs that they all wanted and I was creating specials for all of them including the David Rodigans or whoever. I had what they all wanted so everybody came to me and that worked out for me.

So this is presumably how you linked U Roy for your first tune The Higher The Mountain in 1972?

Yes, I was importing the records and creating the specials and cutting the dubs that all of them wanted. I would take one dub and make many different versions of it. I would take a Duke Reid who usually put out music on 8 track cassettes in those days. He would have the rhythm on one track and music on the other. So I found a way to extract the rhythms, the versions as they were called in those days, and create new specials with effects and/or someone voicing them. So I was interacting with the U Roys and the Big Youths and all of these disc jockeys in those days and that’s how the connection actually came. And he was such a gentleman – I told him I wanted to go into recording and I got the rhythm, told him what I would like him to do and he said “Fine, sure, no problem”. The rest was history.

Yes, I was importing the records and creating the specials and cutting the dubs that all of them wanted. I would take one dub and make many different versions of it. I would take a Duke Reid who usually put out music on 8 track cassettes in those days. He would have the rhythm on one track and music on the other. So I found a way to extract the rhythms, the versions as they were called in those days, and create new specials with effects and/or someone voicing them. So I was interacting with the U Roys and the Big Youths and all of these disc jockeys in those days and that’s how the connection actually came. And he was such a gentleman – I told him I wanted to go into recording and I got the rhythm, told him what I would like him to do and he said “Fine, sure, no problem”. The rest was history.

Did you know Jimmy Radway – the one foot producer? He was voicing Big Youth and Dunkley at that time?

One Foot Jimmy? Definitely. I never had a problem with him. He was a good guy. We didn’t interact a lot but whenever we did we were cool. I don’t know where he is now but a couple of years ago I knew of him. He was somewhere in the country but he’s alive to the last time I knew him.

You produced I Roy’s first album Presenting I Roy in 1973. What was he like to work with?

I Roy was like the intellectual deejay. His command and usage of the English language and his subject matter was so interesting. I never had a problem working with him whatsoever. There are very few people I’ve ever had problems working with – very few. But I Roy was totally different – a little bit of a show off – that’s just how he was wired – but was just a great person. I’ve had the privilege of working with great people to date.

The Big Youth album should have gone down in the Guinness Book of Records because we recorded all the tracks in one night

The Big Youth album should have gone down in the Guinness Book of Records because we recorded all the tracks in one night

How did working with him on that album compare with working with Big Youth on the Screaming Target album?

I Roy was a whole lot simpler and easier to work with than Big Youth. Big Youth had little challenges. I Roy was a whole different ball game. As I remember the Big Youth album should have gone down in the Guinness Book of Records because I think we recorded all the tracks basically in one night, mastered it in one night printed copies the next day and took them to the UK. I think that whole project was done in 24 hours. (laughs) The other day that just struck me. But as I said, I Roy was simpler to work with than most people.

What happened to your association with Big Youth after that album – he went off and did his own thing?

Well Big Youth has always wanted to do his own thing and wanted that sense of independence and control. He had his own ideas of how he wanted to do what he wanted to do so he just evolved doing his own thing.

I’ll ask about one more person from that period – how did you handle working with Leroy Smart?

(laughs) Leroy Smart was a little of a problematic one. You know, everyone knows Leroy. Leroy is all about Leroy and full of Leroy and so much of Leroy. But we completed our task. It was not easy but not difficult.

Would you say you’re a good manager of personalities?

I have had a good working relationship with most people. Not managing them – some of them are just not manageable!

The Simplicity People band you used in the 70s – who were they?

Simplicity People weren’t a specific set of people. It was just a name given to the musicians I worked with at different times and it varied. It was just something to standardise and authenticate a sound and brand.

I understand that but were there any core members who you used often?

(pauses) Yes – Family Man was a bass player, Carlton Barrett was a drummer, the percussionist was Sticky Thompson. There were consistent people but as I said they were changed for the project depending on their availability.

This is a question I have been wanting to know the answer to for a long time – who was the violin player on KG’s Halfway Tree?

I knew you were going to ask that question. He was just a drunkard who had a violin and when he drank he played. I was like “Wow! It’s interesting that nobody is recording anything like this so I wonder what it would sound like if I had him do something?” That was it. I don’t even know his correct name.

Could it have been White Rum Raymond who played on The Tide Is High and many songs from the previous decade?

I was told that name and it is highly possible because White Rum would have been his middle name – some way or somehow!

I help nearly everybody who is ambitious – especially if they display a high level of intelligence

I help nearly everybody who is ambitious – especially if they display a high level of intelligence

You helped the man who would become your biggest competitor in the late 80s – Donovan Germain - enter the producing business in the late 70s.

We attended Kingston College – not at the same time exactly – but we met through the music. He was selling records in New York and I was exporting records into New York. So we had that kind of connection and relationship because of the school and because he was selling records in New York in a record store. That was how we met and he kind of liked what I did so we became friends and associates and that’s how we evolved. I don’t remember exactly what I did but I help nearly everybody who is ambitious – especially if they display a high level of intelligence and they are willing to learn and understand. I have helped Donovan Germain, Specialist Dillon and quite a few people.

Can you tell me about recording Pass The Koutchie with the Mighty Diamonds in 1981 which was re-recorded in England a year later by the group Musical Youth? The tune was huge but things got kind of messy there in terms of who had the right to do what.

We were kind of just doing projects. I decided to, as they say in Jamaica, lick over the rhythm and I gave it to the Diamonds to write a song. They wrote the song and I felt it and the rest is history. The song was so phenomenal but I don’t what led Musical Youth to be drawn to record a spin off. Maybe it was the whole weed thing – they couldn’t sing about drugs so they said let’s sing about food – I don’t know what was their motivation. I never interacted with them or anyone having anything to do with them. They were dealing with the Diamonds because basically it was a copyright issue.

Yes, because it was a licked over Studio 1 rhythm it made the copyright very confusing. The Diamonds have said that there were too many cooks involved.

But that was the greatest thing that ever happened to me in the entertainment industry. Because when that happened I sat down and said “Wow, I created all of this from concept. Everybody is going to make some money and I won’t be party to it. It doesn’t feel right. How do I understand going forward this whole matter of copyright?” That was my first lesson.

I said “OK, going forward, anything we are going to do, we are going to ensure we have controlling interests in respect of the copyright."

I said “OK, going forward, anything we are going to do, we are going to ensure we have controlling interests in respect of the copyright."

From that point you gained a reputation for understanding royalties, copyright and publishing.

I never understood how important it was then so I educated myself to find out what it was and said “OK, going forward, anything we are going to do, we are going to ensure we have controlling interests in respect of the copyright. We are going to try not to do any cover versions in terms of infringement and also in terms of maximising any financial benefit”. So we got educated there and we created a part of our recording process where we had a publishing arm that had all the rights to what we were doing assigned to us. We signed writers and we developed the songs our writers created for the artists we were working with.

So this was essentially the formulation of the ethos of Music Works? How did the company actually start?

Music Works actually evolved from Downtown Church Street where you see the picture on the Right Tracks of that home studio. That was a wooden house with a studio upstairs where we could only cut dubs. Then I moved out of my parents’ house into my own house and we still had the equipment so we turned a closet into a voicing room and voiced Jacob Miller and Augustus Pablo there. Then we left there and rented out premises on Slipe Road where we were selling our records. We decided “Wow, we have so much ideas and when you into other peoples’ studios you don’t have privacy and you want to develop your ideas way beyond what time allows so you have to have convenience to work”. That’s when we decided to build a recording studio. Why Music Works? Because it is the works of music and by the works of music was what we saw ourselves doing so the name just sounded right. So that’s how it all began.

What did you think of the digital thing when it came in in ’85?

When it came in I recognised technology was evolving. That everything was not going to remain the same and there had to be differences. I recognised it and embraced it and went forward into it immediately. That’s just how it is.

Gregory Isaacs is the most quick witted human being I have ever met in my life

Gregory Isaacs is the most quick witted human being I have ever met in my life

When you cut Rumours with Gregory Isaacs in 1988 a lot of people look back on that as the beginning of the revival of roots music. Did you see it that way?

I’ve heard it said but I never thought of it that way. I would guess within that era it did impact. What happened was in those days in respect of the equipment everyone had MCI Sony equipment. We felt there must be other equipment out there so we went to the UK and found another company that made great UK equipment and bought different machines so we did bring in different equipment than what was currently being used in Jamaica. So yes it did make a technological difference in the sound of our music.

How important was an engineer like Stephen Stanley in what you were doing?

The best is always important and to this date he has been, was and still is the best. There is no good that is better than the best.

How important were your team of writers like Carlton Hines Hopeton Lindo and Mikey Bennett?

Mikey Bennett was kind of the leader of the pack and then Hopeton Lindo and Carlton Hines. They shared a view and vision and they were writers who were not basically singers. They contributed immensely to what we contributed to the whole recording industry to date. It would not have been the same without them.

What is your enduring memory of Gregory Isaacs?

Gregory Isaacs is the most quick witted human being I have ever met in my life. One of the most naturally interesting characters. He was funny and didn’t even know how funny he was.

How did you start Anchor Recording Company?

Anchor evolved from our Music Works studio at Slipe Road not having adequate space and facility and privacy. Germain had a studio next door and we felt we needed to move to grow so that was what we decided to do. We found a premises, Greensleeves assisted us to a point and Ras Records just came – I’ll never forget it – and just gave us some money saying “Here is something to just do what you’re doing”. And we just grew from strength to strength.

Anchor evolved from our Music Works studio at Slipe Road not having adequate space and facility and privacy. Germain had a studio next door and we felt we needed to move to grow so that was what we decided to do. We found a premises, Greensleeves assisted us to a point and Ras Records just came – I’ll never forget it – and just gave us some money saying “Here is something to just do what you’re doing”. And we just grew from strength to strength.

Recently you opened your vaults to Curtis Lynch to create his Gregory Isaacs Remixed project. It was unusual for you to give out your rhythms like that, no?

Very. Something about Curtis’ approach and his respectability as a young one I liked. I don’t know what it was. His approach made a difference. He didn’t come with any money. It didn’t involve any money whatsoever. But I am someone who is spiritually connected to people at times and I felt “This is a good young man” so I just gave him a run, you know? I never made a penny. I never intended for a penny to be made. It was one of those things where it felt right so we did it.

What do you look for in an artist?

First of all I look for the song – not the artist. The song makes a singer – not the singer makes a song. If you look at the one hit wonders of the world – that tells it all. I’ll identify the song first and then see what singer the song fits and – if they are willing and we can cooperate and collaborate - we go forward.

The song makes a singer – not the singer makes a song

The song makes a singer – not the singer makes a song

Finally, you had a major hit with Telephone Love in the USA. If you read the Jamaican press today the industry is eager to succeed in the US as you did. What’s the secret?

There is no secret and no formula to success. The outcome of a product depends on the time of the day, the mood or feel of the person. But there are certain main ingredients: the artist should usually have talent and the track should be a great track and everybody should be inspired and share a great vision. Don’t put money first. Put the project first and money will come after.

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2025 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z