Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: David Katz on Jimmy Cliff

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: David Katz on Jimmy Cliff

Interview: David Katz on Jimmy Cliff

"He is one of the heavyweights of roots music"

Sampler

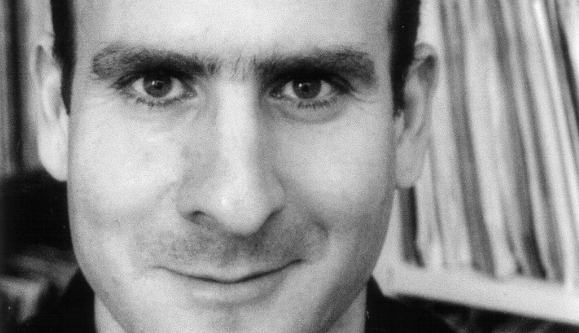

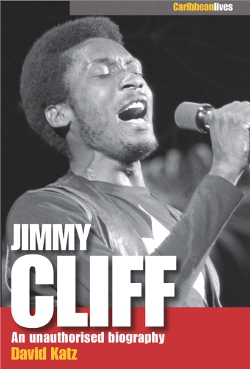

David Katz is the author of the biography 'People Funny Boy: The Genius Of Lee "Scratch" Perry' and the interview-based account 'Solid Foundation: An Oral History Of Reggae'. Originally from San Francisco, Katz relocated to London in the late 80s where he was appointed official biographer to Lee Perry by the man himself. As well as a writer, David is a photographer, radio disc jockey, and chairs the Reggae University at Rototom Sunsplash Festival in Spain. His third book, on another of reggae's greatest figures, 'Jimmy Cliff: An Unauthorised Biography' was published this month as part of the Caribbean Lives series. Angus Taylor met David at a London hostelry to discuss the book, its author and its subject. Below is an excerpt of what was said.

Where did the idea to do a book about Jimmy Cliff come from?

It actually stemmed from the series editor of Caribbean Lives, James Ferguson. We both write for the in-flight magazine of Caribbean Airlines, Caribbean Beat. He got in touch when he was launching the series and wanted to know if I would consider writing a book that would fit. The idea behind the series was short, easily readable biographies of major Caribbean figures, so he asked if I would consider Jimmy Cliff. So really it was his idea!

The subtitle is "An Unauthorised Biography." Was Jimmy approached? Did you have some interview material already?

Jimmy was approached, but he just didn't respond this time round. When you write a book about a music figure, my experience is that very little of it goes according to plan. But I'd met and interviewed him more than once, a number of years ago. That goes back to the time when I was working on my second book Solid Foundation - An Oral History of Reggae. I saw him at a public event and introduced myself, and he gave me his number.

A lot of the other musicians I've interviewed... working with Jimmy was something that they were proud of

A lot of the other musicians I've interviewed... working with Jimmy was something that they were proud of

So you had to use other sources...

A lot of the other musicians I've interviewed have worked with Jimmy, so a lot of them had told me about working with Jimmy just because it was something that they were proud of. It wasn't that I had hunted them down to say "Hey, what about this track you did with Jimmy?" They were like "Hey, I did this track with Jimmy Cliff!" or "I worked on this album". They were all very proud of the work they'd done with him and very struck with his input and the way he approached things. When I was working on this book and when we weren't getting any response from Jimmy I did hunt down a number of other musicians after that, specifically to talk about that, people like Squidly Cole. But a lot of the other material is from interviews that I've conducted over the years.

Who would you say was the most helpful source in the process of writing the book?

People like Tony Chin, from Soul Syndicate, gave me a good feeling for what Jimmy was like as a professional musician and also something of his personality, that he had this kind of strong work ethic and didn't get caught up in the star trip. And Gilberto Gil also told me a lot about this kind of meeting of minds of the two of them, these two very different musical forces that came together for a time, even though they weren't really recording together but they were interacting nonetheless. Gilberto Gil's a very perceptive man so he could kind of hone in on what Jimmy was like, and even though we were talking about things that happened decades ago he can tell you things from the 70s and 80s like it happened yesterday. And then people like Gibby Morrison who told me that Jimmy introduced him to these amazing books like African [Origin of] Civilization - Myth or Reality? [Cheikh Anta Diop], that he had this amazing library that he would bring the musicians there and they would reason and they would read books. Also people like Aura Lewis, who went on tour with him in Africa. Chinna Smith too.

People like Tony Chin, from Soul Syndicate, gave me a good feeling for what Jimmy was like as a professional musician and also something of his personality, that he had this kind of strong work ethic and didn't get caught up in the star trip. And Gilberto Gil also told me a lot about this kind of meeting of minds of the two of them, these two very different musical forces that came together for a time, even though they weren't really recording together but they were interacting nonetheless. Gilberto Gil's a very perceptive man so he could kind of hone in on what Jimmy was like, and even though we were talking about things that happened decades ago he can tell you things from the 70s and 80s like it happened yesterday. And then people like Gibby Morrison who told me that Jimmy introduced him to these amazing books like African [Origin of] Civilization - Myth or Reality? [Cheikh Anta Diop], that he had this amazing library that he would bring the musicians there and they would reason and they would read books. Also people like Aura Lewis, who went on tour with him in Africa. Chinna Smith too.

Even without extensive interviews with Jimmy, one thing that really comes through is how much of his own life he put into The Harder They Come. He is somebody who seems to take experience and feed it back into his own life, his own art.

Definitely. It's often been said that The Harder They Come there was a loose script or there was no script, and it's pretty evident in a lot of those scenes that Jimmy is basically playing himself. That's why he's so believable. It's not to say obviously that everything that Ivan does in the film Jimmy did, but he obviously knows what he's portraying. That's why those scenes like when he's in the market and he goes to try to steal the mango and nearly gets his hand chopped off, that's why they're so believable. There was an edition of The Harder They Come that was released as part of the Criterion Collection and it has this spoken talk-over with Perry Henzell and Jimmy talking about aspects of the film and that validates that view-point.

Jimmy is basically playing himself [in The Harder They Come]. That's why he's so believable

Jimmy is basically playing himself [in The Harder They Come]. That's why he's so believable

Other that things come out of the book are his ingenuity, but also his quite complex relationship with spirituality and with major religions.

He's an intensely creative person and I think he was clear early on that he did not want to be pigeon-holed and constrained by form - particularly once he started to travel. He travelled early, he went to the World's Fair in 1964, so he was barely out of his teens. I think he's one of those people where there's always going to be something good coming out of the pen in his hand and when he opens his mouth you're not going to get something ordinary. I think Jimmy has described himself, and one gets the sense when you consider his evolution and you meet him as a person, he's obviously a deeply spiritual person but he's also someone who's deeply questioning. He's not the kind of person who would suffer fools gladly. In the film Moving On, he talks of himself as a young man in the church community listening to what the preacher's saying and there's some truth in there but there's a lot of things that don't make sense. He's not the kind of person who's going to sit there and think "Well, this doesn't sound right to me but the preacher's saying it so it must be true" or "My teacher's saying it" or "My parent" or whoever it may be. I think he's always been that way and as time's gone on even more questioning and not less.

Jimmy wasn't as public with his involvement in Islam as say Prince Buster or Muhammad Ali were. In the book you suggest his Pentecostal upbringing expresses itself through his music.

As you say, he had this Pentecostal upbringing but he'd already partially rejected it, but with Jimmy Cliff he doesn't throw away the baby with the bathwater, he says "Ok, there are things in this teaching and interpretation of Christianity that I know aren't right" but that doesn't mean that he's going to outright reject Christianity. So he finds his way to Islam first through the Nation of Islam and then later he gets more into traditional Islam and then eventually African Islam as practised by the Baye Fall Mourides in Senegal. Even in that time when he was Nation of Islam or between Nation of Islam and traditional Islam he's still travelling with the Bible, he's still travelling with the New Testament as well as the Koran. So he's never rejected one or the other.

He also went through a phase of getting very close to Rasta. What was his relationship with Rastafarianism?

There's an interview with Jimmy where he does say that he feels entitled to claim Rasta as his own and to describe himself as part of Rasta. When he was a young man there was a Rastaman in his community that everybody shunned except his father would talk to him, and this man fascinated him. Then when Jimmy first comes to Kingston he's heavily inspired by the Rasta camp that Prince Emmanuel Edwards had [the Bobo Shanti order]. So even though he himself was not Rasta at that time and did not identify himself as Rasta, he was already drawing from the Rastafarian influence. He was very close to Mortimer Planno, the Rasta elder and leader. Planno becomes a kind of advisor, they have a series of reasonings. This is at that time where the Oneness band was led by Earl Chinna Smith. Mutabaruka is involved and Jimmy helps to launch Muta's career and then later people like Ini Kamoze and so on. I think there is that sense that Jimmy is very much a Rasta in his own way, in the same way that in a certain sense you could say if you look at Lee Scratch Perry and his version of Rastafari is very, very different from any other being on the planet's idea of what Rastafari is supposed to be. So maybe with Jimmy it's a little bit similar.

He's one of those people... when he opens his mouth you're not going to get something ordinary

He's one of those people... when he opens his mouth you're not going to get something ordinary

The way the mainstream paints Jimmy Cliff is that he wasn't a roots reggae artist. But the book mentions two of my favourite of his roots singles - Let's Turn The Table, on his own Sun Power imprint and Under Pressure.

I'm so glad you said that because that for me was very important to bring out in this book, to highlight that because he's done, as you say, he's done a number of these very incredible, very, very deep roots tunes that are up there with the best and lot of people don't know them or if they ever heard them they forgot it or maybe they didn't even know if was Jimmy Cliff. It's like you say, there's kind of a reggae snobbery about Jimmy Cliff, that he isn't really one of the greats because his music's too diluted, it's too focussed on pop but it's really a totally unfair and incorrect assertion. He is one of the heavyweights of roots music even though he has also done records that were pop. The two are not mutually exclusive. Last time I was in Jamaica I went to this place called Little Ochie in a little town called Alligator Pond, the sound system was playing foundation dancehall, you know early 80s Junjo Lawes type of stuff, then they were bringing them a little more up to date, then for about an hour they played Madonna, early 1980s Madonna. Jamaicans love pop music, and this idea as well that Jimmy's pop records were never popular in Jamaica is also a total myth. Reggae Night topped the charts in Jamaica for months.

The way Jimmy is received in Africa and in Brazil is one of the most compelling parts of the book and, for all those purists, shines a light on what it is about him that was so special.

João Jorge, the leader of Olodum, talks about how significant it was for the people in Salvador up in Bahia in northern Brazil, the more African part, the black part of Brazil. For Jimmy to come, for them it was like this huge inspiration that they really drew from. Olodum created a kind of revolution in music and also in terms of their own local society, and Jimmy Cliff was part of the inspiration they drew from. Peter Tosh was as well, but Jimmy went there and ended up living amongst them and that for them was another heavily important catalyst. Béco Dranoff, this Brazilian music producer and promoter talks about when Jimmy had returned to Brazil for the first time to go to São Luis do Maranhão, this state Maranhão in the north-east, close to the Amazon basin, which is where reggae first had a foothold. He said there were so many people at the airport that Jimmy and his band had to be taken out of the place through the pilot's door and put through a side exit to get them out of the airport without the public knowing! And then this just incredible outpouring and the entire community turning out en masse for this free public performance that when a light tower starts to collapse somehow the crowd manage to make it stand back up again because there's so many people there.

Jimmy Cliff has made many trips to Africa including South Africa in 1980.

Aura Lewis talks specifically about when he was in Africa, she's from Johannesburg, how in Senegal everywhere they went entire villages would be lining the roadsides to cheer for Jimmy. Also the guitarist, Trevor Star talks about when they first went to Nigeria that Jimmy was just treated like a god. So you get this sense of how significant he was to those people there. I've had South Africans, both black and white, they have said to me that everyone remembers when he performed at that stadium in Soweto. He faced a lot of flak for that decision. For years after that event he was still facing sanctions and all kinds of repercussions from it, but he said to me that he knows what he did was right and he knows that the very people who were protesting about him going there, he's on the same side as them. As he says it in the book, they did it their way and he's doing it his way.

In Senegal... entire villages would be lining the roadsides to cheer for Jimmy

In Senegal... entire villages would be lining the roadsides to cheer for Jimmy

Finally there are some very evocative but negative descriptions of Jimmy of arriving in London to work with Chris Blackwell. Would you say any of your own experiences in London have fed into that? Greasy overcooked food and miserable grey days?

(laughs) Yeah. You know in the introduction to my book People Funny Boy I talk about trading my life in northern California for "the grey chaos" of London. And anyone who's ever been an immigrant here, particularly from a very different culture and somewhere where the temperature, the environment and the lifestyle is very different, can probably relate to what Jimmy went through at that time. Yeah, my own experiences weren't quite like Jimmy's and I came decades later. I'm sure it was much harder for Jimmy. But I can relate to what he must have felt at that time from the way I felt when I came!

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2025 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z