Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

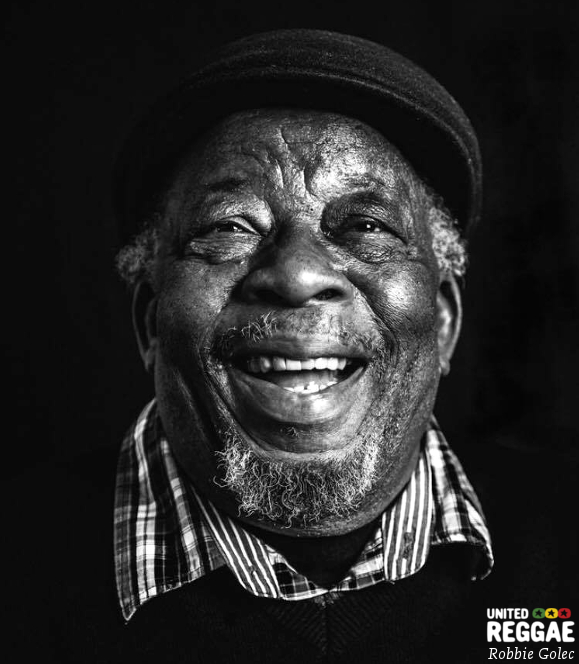

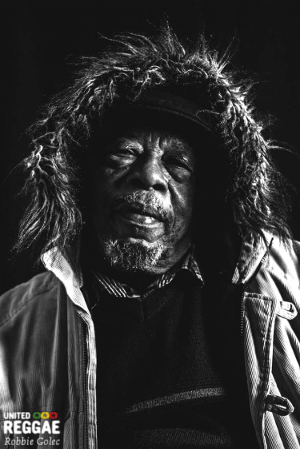

Interview: Enos McLeod (Part 1)

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Enos McLeod (Part 1)

Interview: Enos McLeod (Part 1)

"The more fights you win, the harder it becomes"

Sampler

Deeply ingrained in the culture of seventies Jamaican roots reggae is the idea of the sufferer. For numerous singers and chanters from the era, poverty was not a pose but a painful reality and their music an unashamedly rough-edged expression of that existence. When the decade ended, the American soul that was reggae's conversation partner, shifted away to an increasingly sophisticated sound, as poor man’s pride became passé. Today rappers and dancehall deejays celebrate their riches - whereas many current Jamaican roots reggae artists are educated graduates drawn to its message by choice.

Even by the standards of the 1970s, singer and producer Enos McLeod suffered more than most. He was orphaned at a young age, taking up boxing and door-work to survive while carrying on a bittersweet love affair with music. In the lawless atmosphere of the Kingston and London recording industry, Enos experienced repeated knocks and indignities that were as hard to take as the punches he faced in the ring.

This interview took place at Enos’ home in Catford, South London, in 2012. Due to a series of unfortunate and unforeseen circumstances it has only now been published. Yet what still comes across throughout the discussion is that Enos has not let the struggles he endured keep him down. He is proud of all the great songs he created over the decades. When he plays his last album Reggae Bingy, you can feel his delight in what he has made. Like a fighter after 15 tough rounds, Enos is still smiling and on his feet.

Is it true that you were a boxer before you entered the music business?

I wouldn’t say it like that. I would put it more decent. I would say I was a pugilist (laughs). I didn’t reach a professional stage because of growing up the ghetto without a mother or a father or any proper care, no auntie, no uncle, no brother, no sister - it was just me and Jah himself. It’s tough. To be a pugilist you have to be feeding properly, you have to be sleeping properly. Life was a bit rough. Life wasn’t really easy for a ghetto kid without no-one, so the food intake wasn’t great enough to be a boxer. I started out going on well because I had proper tutoring, I had Archie Moore.

Light heavyweight champion “Ageless” Archie Moore?

The great Archie Moore. He was the one in Jamaica. A place called Tinson Pen, that’s where we used to train. He was my tutor.

What was your weight class?

I was about 135, something round there.

Lightweight?

Yeah, that kind of weight. It was rough work because in the ring you have no help and you have no stone to run and pick up, you can’t run and get a bottle to throw, you have to depend on the gloves. So that was it. The more fights you win, the harder it becomes, then you realise that no, the body needs more than that. So that’s when I said “No. Stick with the music”.

Were the two things happening at the same time for you, in terms of your interest?

No, the music was first. The boxing came because in Trench Town we’d have a guy named Kid Ralph, which was a very good boxer, Bunny Grant, we had a next one named Percy Hayles. Those are good boxers for Jamaica at the time, so they inspired us as kids. But Kid Ralph, he used to live beside my house. I was right there and he was just over there, so that inspired us, the great Kid Ralph. He was a heavyweight. He became famous for bad things, not for boxing, you know what I’m saying?

Right (laughs).

But yes, we started as kids round and round. I mean the Heptones were just over there, Rick Towers up the top, Theophilus Beckford was over the other side, Norma Fraser was there, Toots and the Maytals were round the corner. A lot of singers, you know? Cynthia Schloss was just up the top on West Road, you know, that’s how it goes. And Kingston Senior School, a lot of singers coming out of there again.

My mum died when I was really young

My mum died when I was really young

Where did you go to school?

I started out school but my mum died when I was really young. I don’t even know her. She died when I was like four, something like that. The old man, growed me up, he loved me and he would leave me with no-one; that was my dad. He’d have me in with him everywhere he goes, so I’m not even going to school. He’d have me with him up and down in the sun, oh my God! But I think it was love. He loved his boy and he’d have him there with him.

Then I started going to a man named Teacher Crushlytail. That’s down in Boys Town, next to Boys Town School. You ever heard of Boys Town School? That’s a famous school. That’s where you had Collie Smith, Delroy Wilson used to live in front of it almost, down that side, they call it Rema. Down there, that’s where I started going to this little school with this man. But I could read before I’d go to school because my dad was teaching me, really like home teaching and my little friends. A girl called Beverley, I call her my sister, they’d teach me, so when I started going to school I could read and do what they were doing, better than them.

The first time I went to church there was a crowd, excitement, you know the whole church stopped. Sunday School we used to call it, because they gave me the Bible to read and I was just reciting this thing. I was so fluent there was a crowd around me round me “Oh my God! He can read like that?” So yeah, that’s how it goes.

So was there the option to be a preacher then?

A preacher? (laughs) I used to use that name, you know?

I’m going to ask you about that later (laughs).

(laughs)

My dad was an original Rastaman

My dad was an original Rastaman

I just wondered whether that came from having the real experience.

Well, all these things came from my dad because my dad is original Rastaman. Original Rastaman. I mean he didn’t have the locks because of survival, and in those days if you carried the locks police beat you bad, you know? In those days they used to beat Rastaman, bust up them head and things like that. So my dad, he’d teach me to read the Bible, that’s what I first learnt to read – the Bible. He’d teach me to pray, he’d teach me “You have to learn the Bible” and telling me about Marcus Garvey and telling me about culture. My dad was a great singer. My mum as well.

So it was inborn in you then?

Of course! I think before they started having sex they were singing (laughs). I have the brain… I have the memory of an elephant and I can remember being that baby boy, three year old, four year old, I still vaguely can remember my mum and my dad singing. I can remember that. Oh God, the sound is coming from their mouths but I can’t see the sound and I want to see it, but I didn’t realise that sound was invisible at the time. Then after she died, me and my dad were together and he’s always singing. He said he’s better than Bing Crosby, he said he’s better than Billy Eckstine, if you know these singers? Roy Hamilton. You know, I’m coming from way back.

How did you enter the music business?

First, at the age of about 10, 11, I would save up a penny, a ha’penny – you know what a ha’penny is? A halfpenny. I would save up that until I had a quatty, which is penny, ha’penny, and I would buy the newspaper because I would be listening to a thing called Radio Fusion. We didn’t have radio like radio – we had this little box that you hire from RJR, maybe just the one channel and you have to listen to that.

So because I used to listen to my mum and my dad singing I loved to hear it coming out of the box, and the newspaper called The Star used to put songs in it from those singers played on the radio. So I’d make sure I’d buy a Star, I’d save up my halfpenny to reach a quatty and buy a Star and cut the songs out and paste them into a book, so I can have them to read them and learn them and sing them. That’s how I started.

And then what was your first break into recording?

Sad. My first break into recording. I used to go down Love Lane where Sir Coxsone used to be, you used to have a man named King Edwards, and a man called Vere Johns. Vere Johns used to have stage shows all over the island. I used to follow round the sound systems, so I could hear what was going on. It was just this inside thing from them. You listen to them and you want to be as good as that singer. You want to be like Johnny Ace because Johnny Ace is so great.

I would hitch around between Bells “The President”, King Edwards “The Giant”, Sir Coxsone, Duke Reid, and that’s where it started. So I first went to King Edwards because my friend called Tunnyman, may God rest him in peace, he used to sing for them. But these songs wasn’t like songs to release, you know? These songs were songs to play on the sound system, like this sound system is going to play against that sound system so he puts on this record that that one don’t have, and that one would do the same thing. That’s how most of Coxsone’s songs came as well.

I would hitch around between Bells “The President”, King Edwards “The Giant”, Sir Coxsone, Duke Reid, and that’s where it started. So I first went to King Edwards because my friend called Tunnyman, may God rest him in peace, he used to sing for them. But these songs wasn’t like songs to release, you know? These songs were songs to play on the sound system, like this sound system is going to play against that sound system so he puts on this record that that one don’t have, and that one would do the same thing. That’s how most of Coxsone’s songs came as well.

It wasn’t really like sales of records either but I had people like Theophilus Beckford topside me, living up there. This is before even Heptones started recording. You had like Lloyd Clarke, who I came and produced big hits with at that time. You have this Norma Fraser, who did First Cut Is The Deepest, then Toots and the Maytals. When I saw Toots come into Trench Town as like a country youth, because as a town guy you’d look at a country guy like “Oh likkle country guy” you know what I’m saying? You look down on them as a country guy. He’d be playing his guitar like hell… and I’d say “What’s wrong with that jonkanoo guy? Jonkanoo business”. You know what a Jonkanoo is? At a festival dressed and he’s playing [energetically] and what the hell is that man? I didn’t rate that.

But then he went on to Coxsone and he started doing well and my friend started doing well and he started singing some tune like Sligoville Town. He took me down to King Edwards and I did a song for him and the song is (sings) “See the moon come stealing, in the heaven above, sweetheart it’s appealing, to the one I love”, that was the song… but I didn’t like it. No, because you have to go there, you have to stand up, you have to wait, you have to come again and you have to go again. I couldn’t take that, with none of them I couldn’t take it.

When I saw Toots come into Trench Town... I’d say “What’s wrong with that jonkanoo guy?"

When I saw Toots come into Trench Town... I’d say “What’s wrong with that jonkanoo guy?"

What, like audition or…?

Not even the audition, because if you get through to the audition then that’s fine, you’re reaching there, but you’re there for days, going there for days. Sometimes you’d have to leave school, you’d bunk, you get me? And then… and that’s how it goes.

What was the title of that song?

The Moon Come Stealing. That wasn’t even ska or nothing like that, that was a sort of rhythm and blues style, because this was even before the ska thing came in. This was before rocksteady comes. This is when they used to play that (sings) “badoom-boom” - the big standing bass, some boogie some kind of thing and some American style. That’s the type of pattern the music thing was like.

So what year was that then?

I would say ’59, ’60, something around that because my dad died in ’62 when I was 16.

So what happened? They just played those tunes on the sounds and that was that?

Yep. Yep.

And what did you do after that? Did you leave music for a while or did you carry on?

When my dad died things got rougher because no dad, no-one at all - no mum, no dad, no auntie, no uncle, no brother, no sister. There was no-one, just me alone and Jah now. This is Trench Town, you know? In Trench Town you have to be tough, you know what I’m saying? At the same time the boxing started kicking in as well, so it started to get rough. When you’re by yourself you start realising “Father really dead now, Papa really dead”. Because you’re hungry now, you have to start look your food in desolate places now, start to become a man now (laughs).

In Trench Town you have to be tough

In Trench Town you have to be tough

So you turned to boxing then?

You know, we not even reached there yet because I used to be– you’re the first one that’s going to get this – an apprentice jockey.

Yeah?

You’re the first one going to ever hear this. But my stepmother, she for some reason was like the dirty stepmother, she don’t like me because my father loved me. She was having children from my father and my father maybe loved me more than those children, so she don’t like this one, so me Cinderella in this story, yeah? You understand what I’m saying? So me being a jockey made me a bit too successful or something like that. My friend’s a jockey called Frankie Frazer, he died - fell off a horse and it stepped on him and killed him at Knutsford Park. I used to be around the stables of Sergeant Bucknor. One of my friends called Piper Roy Sanders was the top jockey for his stable, he’s blind now for whatever reason.

And how did that go?

Faded out because “You’re getting too big!” to be a jockey (laughs). So it still comes back to music. But when my dad died now, badness and badness. I was like in jail, three of us.

How come?

Badness and badness (laughs).

(laughs)

One man got bail, they shipped him out to England because they didn’t want him to go to prison, the next man got out, bailed out, leaving jail like this. Admiral Town station. I didn’t have no-one but I had the Almighty. For some reason they opened the door and said “Well you getting your bail” So I had to run, come to Two Mile to my mum’s brother, which is my uncle. He’s a big politician. I ran out there to him and ran round there with him, he had the work, he treat me no good same way. That’s when the boxing come, that’s when I went to Tinson Pen and the music put on hold like.

What year was this now?

This was ’62, ’63, ’64, around then. Out at Two Mile the next big sound was named King Prof, my uncle’s sound named Sir Bobs The Young Giant, then we had Dennis Alcapone with a sound called El Paso up by Brotherton Avenue, just beside me there at Two Mile, you know what I mean? Owen Gray used to come from the next lane. There was a circle of music people that still I found myself around. John Holt lived up the top of the Waltham, up Delamere Avenue on the side there. It was just the music still faced me everywhere about, same way. But boxing come now and that’s how it started. You get bigger and you realise you’re not fed enough to do the boxing because you can’t work out, so that put a halt and it’s music again.

I was in the first Itals

I was in the first Itals

Who did you go to then?

Sir Coxsone formed a group the Itals, this is before ’67 though. I was the first Itals even before plenty of these guys came from country to Kingston and started saying they are the Itals. I was the first Itals. The Untouchables, I was the first Untouchables. To prove these things, you go back to 1967 and ask these guys who said they're Itals and say they’re Untouchables, ask them if they were around 1965, ’66, ’67, then you will know who is the true and original Itals and Untouchables. Universal have some song out for me now on the album called Socking Good Time. That’s my album. A load of those tracks are mine.

Who was in that Itals group?

Me, a man called Raggu, and a next brother called Pardie. Three of us. Raggu was one of the first men who started to make festival, fried festival, fried dumpling – we call it festival, with salt fish. He was one of the first men who started that, in a lane called Well Side Lane. That’s when the Itals started. We were called the Itals because of the Maytals and because used to smoke Ital weed. We never touched cigarettes.

But remember, I used to go all around with the festival thing. In the festival time I used to write my song and send in my song and things like that. That woman, Miss Pottinger, she’s a bad woman to me because she was one of the judges, you know what I mean? For some reason she never liked me. Very rude – “You come from the ghetto” and things like that, to put you down. That’s how it goes, and the Itals never reached anywhere.

We came back and started the Untouchables – that’s me and a guy named Denzel, and a next guy from downtown from Tivoli Gardens, he used to do cabinetwork, and a next one called Blinks, he had kind of a cast eye, like. So it was me, Denzel, Blinks, and the next one, Untouchables. We did a lot of songs, we sang on that album Socking Good Time. But then it’s history again. But I did songs before that, recorded songs before that, you know? Because I was with Sid Bucknor, Sid Bucknor was my teacher before I reached that stage.

I was going to ask you about that. How did you meet Sid Bucknor?

Studio One, the time Coxsone came up Brentford now on the Brentford Road and Sid Bucknor was there amongst them. Sid Bucknor would check for me as a little youth and send me go buy this, send me go buy that. Me willing, and enough of the man there amongst them were not willing and stuff like that. So that’s how it goes.

I did a song called Too Late Shall Be Your Cry and I did a song called Mackie Mackie, those songs I did. But those songs were my songs, you know? I spent my money on producing those songs. I didn’t sing them for no-one. I did this song called Soul And Inspiration with the Hamlins, you know that group? (Sings) “Oh please, don’t you say goodbye, cos you know that I’d cry, oh please, you are my soul and my inspiration”.

Studio One put that out but it was my rhythm, I did that rhythm for Studio One for Sir Dodd. I was going to sing that song for Sir Dodd but then I left and I went away so Dodd said the Heptones should do the harmony with me, because we come from the same place but every time I got to Heptones they’re not paying me no mind, they’re not rehearsing with me, they don’t even want me beside them. That’s the whole truth, you know what I mean? I didn’t get to it so these guys come and Sir Dodd put Hamlins on the rhythm. That’s how those guys got that rhythm, but that was my rhythm. But by then I did Mackie Mackie and did Too Late Shall Be Your Cry. One called La Bamba…

Miss Pottinger... For some reason she never liked me

Miss Pottinger... For some reason she never liked me

Yes, a duet by Enos and Sheila.

With me and Sheila, that was a festival song. That song made it in a theatre called State Theatre who until this day never worked with me again as a theatre. Because you had the Heptones on that show, you had everybody! Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, you had Desmond Dekker. It was Desmond Dekker they gave that festival show to - and me and Sheila came up on that.

She was the Melodians’ girl, Brent Dowe’s girlfriend, Sheila. Me and Sheila came on but I cut my hair in a mohican, shined the two sides of the hair in the middle, Vaseline this side and Vaseline this side, so when the floodlight come on and me and Sheila and the place goes wild! And the rhythm you know, is a very good rhythm, a Studio One rhythm, a class one rhythm.

So the place got wicked and the people who were outside wanted to know what’s happening inside of the theatre. They got crazy outside because the crowd was bigging us up, a massive show that was, it had on a lot of artists. They started breaking down the door to come inside. Now the people inside, when they saw the doors start breaking down and people coming inside and excitement, they started to stampede outside, so some coming in and some going out and the whole place mashed down. And that was the end of that.

Was it Sid Bucknor who taught you your way around a studio, engineering, production, things like that?

I’m not an engineer but I have ideas and know the sound and know what I want. I can tell you what to do, I can tell you when you’re wrong. Give that to Sid Bucknor. But to sit down round the board and use the keys and this and that, I’m not good at that. That’s not me. That’s a bit too much for me. But yes, it was Sid Bucknor.

So what kind of things did he show you?

He taught me to identify sounds. Like I could be listening to the whole rhythm playing and he would say “Mackie!” – he called me Mackie, he would say “Mackie, what is the rhythm guitar playing? Tell me the sound” and I’d say “Chuc-uk-chuc-uk” and he’d say “Yes, you will learn” and he’d say “And the percussion? What about the percussion?” and I’d tell him. He’d get my ears… inside. I can hear 17 or 20 different things on a tape and I can identify every one of them, until this day. And that’s a great thing in producing.

I was one of the first to mix country and western with Jamaican music

I was one of the first to mix country and western with Jamaican music

How did you start producing?

A big thing happened. Melodians used to rehearse in Well Side Lane with me. I was one of the first persons who started to mix country and western with Jamaican music. I have a friend named Val, he’s rich – rich, rich, rich, and he lives in California now, done with Jamaica. He used to have me beside him and he used to go to Derrick Morgan in Greenwich Farm and we’d go to Gunboat Beach. He’d drive a big truck and he’d come and pick up me and he’d pick up Derrick Morgan and we’d sing and sing at the beach. But he liked the country and western thing that I was doing, so he would say “Sing, sing” and he’d give me money as a youth, keep me going, you know what I’m saying? He left and the thing washed up like that.

So what really happened is now, there was a place called Paper Factory, it was burnt down, and I’m not doing anything. So I asked the foreman for some work and he said “Yeah, come in Friday evening and you get some”. I didn’t see him the Friday, so when I see him the Monday I said “You tell me to come Friday and when I come I don’t see you”. I just beat him up. Because I was like that you know? Beat him up bad and he run and he go over there and tell the boss “some guy out there named Musso” beat him up.

The boss came because he had a lot of police and they just come and kill you, you know? I go to the boss and the boss said “Why you beat up my foreman?” I said “Well, the foreman said he would give me some work and I can’t thieve, I’m not a thief, I’m glad for the work, for the opportunity and I had a place I could go”. This was just an excuse, you know? I couldn’t get to go because he make I was there waiting, and he said “You really want some work?” I said “Yes, boss”. So the boss said “Alright then. Start work tomorrow”. I said “Nice”.

The boss had this big, deep pit. You walk on a wooden ladder and it's going like that when you walk on it makes shaking noise it shaking. I thought "I am not used to these things". But the first time I get my lunch break and build a spliff and eat the food I just start singing. And they go and tell the boss "He's not working. He's just singing". So the boss called me and said "How you say you want to work?" I said "Boss, let me tell you. This is not my type of work really". He said "But you want work? You eat up the food and say you want work and I personally gave you some work so why are you not working?" I said "Boss, I am a singer. Not this kind of work. I am a singer." And the people said "Yeah man, he is a good singer. He’s done some recording". The boss said "You say you are a singer for true?" I said "Yes sure". "Where your mother?" "She dead". "Where your father?" "Him dead." He said "Okay, listen, stay with me, don't bother to go back into the hole. Sit down".

So I sat down beside the bus for the whole week as he drove up and down and the boss gave me a fat envelope stuffed. I thought "Sweet". The Boss said "I am going to let you go to the studio and get your musicians and I am going to pay for all of this and you're going to do your music". I said "Thank you, boss". And the boss gave me an envelope every week. So I went to Lloyd Clarke because I knew him for a long time and I said "Listen because you're a good singer I want you to come and sing a song for me or two songs".

So I got Lynn Tate and the jets and we went to Dynamic Sounds. It was West Indies Records – WIRL - before it changed to Dynamic. I did Young Love, You Can Never Get Away, Prisoner In Love, Wallflower, and all those songs. La Bamba we didn't make there. That was Sir Coxsone and those are different songs. All those Untouchables songs that are on Socking Good Time that is me. They don't even know it's me. But if you listen to the songs then you can hear the same musicians.

So I got Lynn Tate and the jets and we went to Dynamic Sounds. It was West Indies Records – WIRL - before it changed to Dynamic. I did Young Love, You Can Never Get Away, Prisoner In Love, Wallflower, and all those songs. La Bamba we didn't make there. That was Sir Coxsone and those are different songs. All those Untouchables songs that are on Socking Good Time that is me. They don't even know it's me. But if you listen to the songs then you can hear the same musicians.

And Young Love was a hit wasn't it?

1967 that was. Big hit. Miss Benson, she used to work for Federal which was the Khouris. They branched off and opened a company called Record Specialist up by Racecourse, by Torrington Bridge. But she loved me you know. That lady loved me. Everybody loves me dead. She said "Enos, you stay with me, I am gonna see you all right". I said "Alright Miss Benson". She got in touch with somebody in England and they said they wanted Young Love to release. This was Lee Gopthal. She says to me "Enos, they have to deal with you good because they are coming through me. They're not coming through and dealing with you and I don't want your money". So she got the deal for me and it was the first time I had so much money in my life. And that was big money. In those times. Young Love was my first hit. That was in 1967.

Young Love was my first hit. That was in 1967

Young Love was my first hit. That was in 1967

So how did other songs from that time come out in Britain like You'll Never Get Away with La Bamba on the other side?

What happened was this guy Clancy Collins got himself in trouble I think in England so he had to run away and come to Jamaica. They thought he was running from the police or something - that's what I gathered at the time. Now when he came to Jamaica he was trying to put up a studio and he couldn't make it in Jamaica. He hadn't got a clue. He didn't know what he's doing. Trying to come into the music business in Jamaica. So what really happened was he got himself in trouble with a gun. And he conned the policeman and told the policeman how he was from England and he was going to get some money coming down from England and give the policeman some money. But he did not have any money to give the police - he was only feeding on bun and cheese and soda. He was broke.

Merlene Webber that singer, me and her were friends. Bunny Lee used to say "She your girl" but it was nothing like that. We were good, good friends. So I said to Collins “Me and Merlene we're gonna help you. I am going to give you some music so you can go and look for some money from me. So mean you will have some money”. So I gave him some tracks. He is the one who I think brought these things to England and gave them to these people. I gave him the tracks and said "Take these tracks so that I can get some money and you can get yourself out of this mess". And that man is a wicked man. Clancy Collins is one of the wickedest man upon the face of this earth.

Is this Sir Collins? Sir Collins Wheel?

Yeah man! He is a wicked man. Because I helped him so that he could run away from prison in Jamaica. They were going to send into prison with that gun charge and he didn't have the money to give them. He ran back and came to England with the music and he got money from Trojan. He didn't even send a penny and give me anything to help me with my kids that I had started getting as well.

I can't leave music!

I can't leave music!

So what did you do then? Where you finished with music for a bit?

I can't leave music! Ansell Collins and all those boys there, they organised and did me some instrumentals like Hot Coffee and some more music. I produced more music. I couldn't stop. I didn't have anything to go to. At one time the thing got slow and I had to open a restaurant on Bell Road. On the bottom side of Dynamic company. This is like 1970 or 71.

Why did you take the name Preacher for some of your recordings?

I finished with the Untouchables. I finished with the Itals because when I wanted to sing, this man didn't come to rehearse and then that man didn't come to rehearse. And when we needed to go somewhere this man can't come or that man can't come. So I said "You know what? I am going to do this thing on my own".

I did this thing called Moon River. I think the Police heard it and they got big from that song. So I just left everybody and started singing on my own. Enos McLeod wasn't doing the thing and things were getting hard. It was just Johnny Clarke and Al Green. Those were the only people selling at that time. Everything got slow. Even Bob Marley wasn't selling. So I just held the Bible. That's how fluent I was. And started reading from the Bible behind the mic at Tubbys studio. And it was pure psalms I would chant. So I called myself the Preacher.

Did you do a cover of the theme to shaft for Derrick Harriot. Black Moses?

No.

That was credited to the Preacher as well.

I don't know. I would have to hear it. They are criminals. They do things like that. I did a song called I Have Made Up My Mind and Joe Gibbs didn't put my name on it. He put Michael Rose. These people are criminals. They do things like that.

I am always unlucky

I am always unlucky

So what happened next?

Then I did No Jestering with Shorty the President. I was the one who put the Micron Company on the map. Pete Weston, Ronnie Burke, Michael Johnson. Rupie Edwards had a young Johnny Clarke at the time. Johnny Clarke had a song called Julie Don't You Know for Rupie Edwards and it started selling in England. Bunny Lee was up and down frequently between England and Jamaica so Bunny Lee realised that Johnny Clarke was going to be big because they liked Julie. So Bunny Lee run up and did an album with Johnny Clarke and took over Johnny Clarke from Rupie Edwards.

But he had an artist called Shorty the President with [Yamaha Skank]. The (makes high pitched backing vocal from the tune) “screw screw screw” that's Flabba Holt doing those things there. So I looked and I said "Rupie is going to get a double beating now because I take away Shorty the President now". Carl Malcolm at the time had No Jestering so I said "Shorty, I have a tune. This is a hit. It can't miss.” This was late 1974 coming into 1975. He said "How you know that a’go hit?" I said "Me know the music a’go hit". He said "Every day a youth man says he has a hit". I said "Just cool man, this is a hit."

I got Shorty the President, and me and Soul Syndicate went to Channel One and played and recorded the song. The first week it went straight into the charts. Jestering was a hit. They brought Big Youth to try to catch it with “Mr Fester from Manchester”. But I had the wrong people again. I am always unlucky. I came upon a guy called Pepe Judah and his brother named Hubert Campbell. Ital Records. Pure criminals them. Wicked thieves and criminals those people them. Pepe Judah and his brother. I tell you man. If I told you what those people did to me you’d cry.

PLEASE NOTE: THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THIS INTERVIEW ARE THE VIEWS OF ENOS MCLEOD AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF ANGUS TAYLOR OR UNITED REGGAE.

Read part 2 of this exclusive interview with Enos Mcleod here.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2025 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z