Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Al Fingers on Clarks in Jamaica

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Al Fingers on Clarks in Jamaica

Interview: Al Fingers on Clarks in Jamaica

"In Jamaica Clarks are worn by gangsters... but people in England perceive them as a sensible shoe for kids and grannies"

Al Newman AKA Al Fingers has turned his deft digits to a variety of musical and multimedia projects over the years.

In his time he has been – and still is - an author, a designer, a dj, remixer, album sleeve designer and co-curator of the globetrotting Art in the Dancehall exhibition – which came to Los Angeles this month.

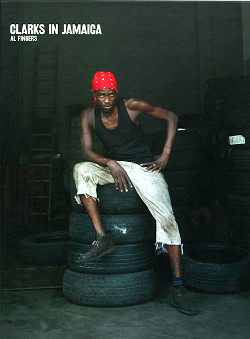

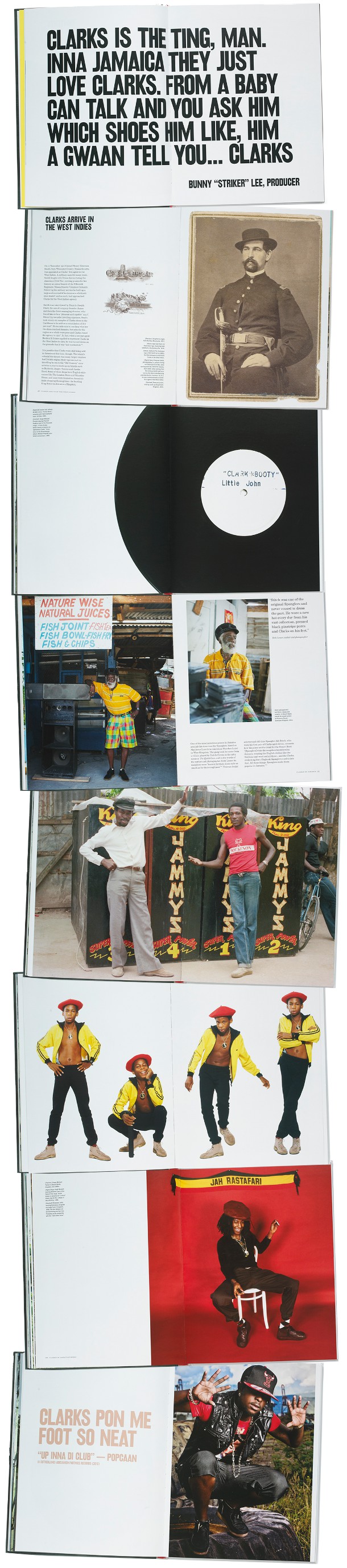

His latest self-published book, Clarks In Jamaica, tells the curiously fascinating tale of how a stuffy and safe English shoe company became the hottest brand on the island and intrinsically aligned with the development of reggae and dancehall music.

Angus Taylor caught up with Al to hear a tale where the only thing that was predictable was how the least expected outcome inevitably came to pass.

How come you’re called Al Fingers?

The actual reason is embarrassing. Nothing cool about it. I used to work part time in the office of Blues and Soul magazine where I used to produce this hip hop magazine called FatBoss with some friends. I was typing up interviews and I can type really fast so Roy the publisher of Blues and Soul saw how fast I was typing and came up with the name. He started calling me Al Fingers. Then because of djing and playing guitar it kind of stuck.

I think pirate radio in England is some of the best radio in the world

I think pirate radio in England is some of the best radio in the world

What got you into reggae and dancehall?

I guess growing up in London it’s very much part of British culture. It’s a lot more integrated than it is in somewhere like America where there are obviously a lot of Caribbean people but the culture is not so integrated into mainstream everyday life. I think pirate radio in England – Vibes, Roots, Unique, Beat, Station FM, etc - is some of the best radio in the world in terms of selection. I’ve always loved music and although I wouldn’t say reggae was my earliest music I got into but it’s so readily available here that if you love music you’re going to get into reggae at some stage.

How did you decide to write a book about Clarks in Jamaica?

I’d just finished a book about the album cover art of Greensleeves records. I was talking to a good friend of mine, Pierre [Bost] who runs the Special Delivery label, about ideas for new projects I could work on. Vybz Kartel had just released Clarks and the two followup tunes so having been to the Caribbean and seen the love of Clarks firsthand where I was being asked “I beg you to send me some Clarks” while knowing how Clarks were perceived in England I thought “this is something that has never been documented”. It’s kind of niche and off the wall but there was a story there.

Why did you decide to put this one out yourself?

Books are never easy but having produced books in the past I kind of knew what I was doing up to a level of submitting a book to a printer. I’ve never really made anything out of books once they’ve come out because the publisher takes such a big percentage of the price and I’ve never really been impressed with how publishers push a book – it’s always had to come from the creator of the book to promote it - so I thought I would try to publish this one myself. So it wasn’t a case of pitching it to a publisher but I did need to get the funds to do it – which is basically what a publisher does. The workload was pretty high because I was doing everything from the research to the writing to the retouching to dealing with photographers and artists.

Books are never easy but having produced books in the past I kind of knew what I was doing up to a level of submitting a book to a printer. I’ve never really made anything out of books once they’ve come out because the publisher takes such a big percentage of the price and I’ve never really been impressed with how publishers push a book – it’s always had to come from the creator of the book to promote it - so I thought I would try to publish this one myself. So it wasn’t a case of pitching it to a publisher but I did need to get the funds to do it – which is basically what a publisher does. The workload was pretty high because I was doing everything from the research to the writing to the retouching to dealing with photographers and artists.

In the book it’s clear that the Clarks Desert Boot took off in Jamaica post-independence – was there any desire to bring it out in 2012 for Jamaica 50? Did Jamaica’s desire to look back on itself help?

That was a coincidence. I’d started it a couple of years before. I knew it was coming up and thought it would be great if I could get it out then. Coincidentally it was also 100 years after Clarks first came to the Caribbean. I guess it helped – especially with the Jamaican success in the Olympics – but I think the main interest outside of people who are into books centred on reggae was that in Jamaica Clarks are worn by gangsters whereas here it’s the complete opposite. I think that is what has really grabbed people’s attention. I would never have expected it to be on BBC Newsnight but people in England perceive Clarks as a sensible shoe for kids and grannies.

How supportive were Clarks themselves?

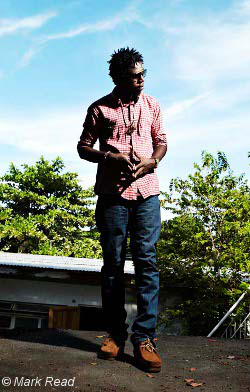

They’ve been pretty supportive. I approached them in the first place with the idea for the book because I wanted to go to Jamaica. So they helped a bit and gave me a quantity of shoes I could take with me to give out to people who were involved in the book and their press agency have helped me in certain ways. When I came back from Jamaica with the material we did – I had a photographer with me who took some amazing photos – it was always my hope that Clarks would think this was great stuff and want to do a campaign around it. Unfortunately they didn’t but then I can’t complain because I suggested they do something with Vybz Kartel and then he went to prison which would have been an absolute disaster for Clarks! But there are artists like Little John for example who could be the centre of a great Clarks campaign.

What was the most enjoyable part of researching the book?

Going to Jamaica and meeting my heroes. I was hoping to meet Vybz Kartel and Popcaan. They’re my favourite modern Jamaican artists apart from Sizzla and Beres Hammond but unfortunately I didn’t get to meet them. I went with a long list of people who I listen to and respect. I had to see Little John. Characters that really made an impact in terms of what they had to say were people like Jah Thomas and Trinity – and people I never expected to meet like Ansell Collins. Jah Thomas was one of the main people who went to England in the 80s and sourced and brought cheap Clarks back to Jamaica – along with Junjo (who was actually shot dead here in Willesden). But also going to Clarks in Somerset and looking through their archives at stuff that hadn’t seen the light of day for years. That’s what I love about doing a book: seeing what I can find and then bringing it together into what I hope will be a coherent story.

You went over there with Special Delivery and that was when they met Chronixx who is now the hottest young artist in Jamaica.

You went over there with Special Delivery and that was when they met Chronixx who is now the hottest young artist in Jamaica.

Yeah. We were in the studio when Chronixx was voicing Beat and a Mic – he’s a Clarks man himself so he’s in the book as well as some of his crew! What happened there was Chris Hurst from Acoustic Vibes label who we went round Jamaica with said to Pierre that there was this new artist we should really meet and that’s how the whole link happened.

As reggae turned into what became known as dancehall artists began to sing about more everyday matters – did this help the rise of Clarks?

Dancehall artists do have a habit of going into the studio and singing about what happened ten minutes ago. There was a tune by Trinity (kind of before dancehall but anyway) called Clarks Shoe Skank about how he went into a shoe shop in Kingston to buy some Clarks but they didn’t have any and sold him some pointed shoe alternatives. He was pissed off about it and went to the studio and sang a song. I met Trinity out there and I don’t think he remembered the tune. It’s amazing what dancehall artists sing about but that’s part of the appeal.

Dancehall artists have a habit of going into the studio and singing about what happened ten minutes ago

Dancehall artists have a habit of going into the studio and singing about what happened ten minutes ago

It’s interesting how Jah Thomas says that rude boys liked Clarks because they were quiet and you could sneak up on people but Rasta people liked them because they were natural and durable. Why do you think Clarks have made such an imprint on Jamaican culture?

(laughs) There are various reasons why I think they are so popular in Jamaica. Jah Thomas’ one only he told me but makes sense if you were trying to rob someone! The Rasta thing was the whole ital thing. Clarks are all natural materials – the uppers and the soles – and the fact that they lasted for years and years was definitely a big reason why they were so popular as well as the comfort because a lot of people walk quite a distance in Jamaica. Then there’s the English link because of people coming from Jamaica to live in the UK and travelling back and forward. And the look of the Desert Boot is a good looking shoe that can be worn with various types of outfit – smart or casual. One of the things I didn’t put in the book was said by Patrick Cann of the Arawak label who used to be a big importer of Clarks in Jamaica and used to sell thousands. He said that in Jamaica there is a funeral every week and you can’t be seen wearing the same shoes as at the last funeral – so you have to go out and buy some new Clarks booties.

What really comes across in the book is how little of this story unfolded by design.

Yes. Clarks never really pushed their shoes on Jamaica. Clarks marketed them in the 40s and 50s but when the political situation changed and Manley came in Clarks found it very difficult to import into Jamaica. They were interested in the Caribbean but the Desert Boot actually became big in Trinidad before Jamaica. When Manley put import quotas to support Jamaican industry and then banned the import of footwear altogether Clarks lost interest. Tony Thorner who was in charge of Clarks exports and who used newspaper advertising to create this image of Clarks as a well-made English shoe, a luxury item lost interest and turned his attention to the far East. At that point Jamaicans took it on themselves to bring them in. There’s never been a Clarks shop in Jamaica. There hasn’t been advertising there since the 60s. Even now there are only three official stockists in Jamaica. Before Vybz Kartel’s tune there might have been one.

Clarks never really pushed their shoes on Jamaica

Clarks never really pushed their shoes on Jamaica

The biggest numbers of Clarks tunes come during the Seaga years. Was the story of Clarks the story of a colonial product and the triumph of consumer capitalism in Jamaica? Or was the story too grassroots and organic for that?

When Seaga came into power capitalism blossomed. Seaga lifted all the quotas and things Jamaicans previously had a lot of problems getting hold of in terms of clothes and electronics could suddenly enter the country much more easily. But it still wasn’t Clarks doing that – it was Jamaicans bringing them from England and America – so I would say it wasn’t Clarks exploiting this new Jamaica. But as you say the 80s was the peak time for Clarks in Jamaica. Various artists told me if you didn’t have Clarks on in the dancehall back then – you weren’t anything. If a girl saw you didn’t have Clarks – forget about it!

Finally, it says in the book that Nathan Clark based his initial design of the Desert Boot on a shoe he saw in British soldiers buying in Cairo – so could you say that the Clarks Desert Boot came from Africa?

Yeah. I suppose you could. (laughs)

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z