Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Chris Lane, Reggae Writer

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Chris Lane, Reggae Writer

Interview: Chris Lane, Reggae Writer

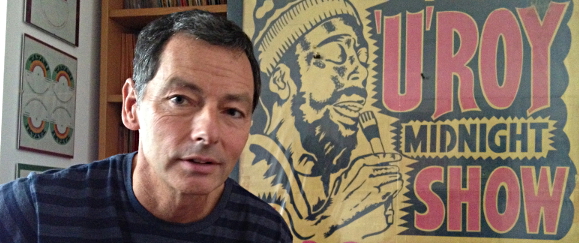

"I went from something that I sort of enjoyed to something I enjoyed a lot more"

Last spring when United Reggae spoke to Chris Lane (along with his Fashion Records and Dub Vendor co-founder John McGillivray) it was in his capacity as a producer, musician and engineer. But as true heads will know Chris was also one of the first people to start writing seriously about Jamaican music in the 1970s mainstream UK music press. Most specialist reggae writers today will relate to the fact that Chris only ever wrote part time in conjunction with a variety of day jobs. But despite his articles in "Blues & Soul", "Black Music", "Melody Maker", "New Musical Express", "Let It Rock" and "Music Week" being hard to find without a visit to the British Library archives, many of them are still passed around internet forums in a virtual atmosphere of hushed awe. Last summer Angus Taylor visited one of the founding fathers of his profession and spent an enjoyable two hours listening to records and having this rambling open-ended chat. Opinionated yet never arrogant, Chris had plenty to say. Part one is published below…

You're originally from Islington, but you moved around London a bit?

Yeah, I was born in the Angel. My dad was a copper. In those days they used to get free accommodation. So we were living in a house in Barnsbury Street and then we moved to Marylebone, to these flats called Macready House which are now luxury flats, like the place where I was born; the Royal Free Hospital in Liverpool Road which is now luxury flats (laughs). When I was 16 or 17 we went to Belgravia to another block of police flats which has now just been knocked down and luxury flats are going to be built. It's like this recurring theme in my life that everywhere I live, after I've moved out it becomes luxury flats. When I left my mum and dad's house I lived in Battersea for a couple of years, then I lived in Aragon Tower on Pepys Estate, which is now, guess what? Luxury flats!

You had a private school education at Latymer Upper in Hammersmith. What kind of stuff were you good at in school?

Winding up the teachers and annoying people, more than anything! I wasn't particularly academic; in fact I wasn't academic at all. I enjoyed English but I wasn't particularly good at it. I wasn't really very good at maths. I was just probably slightly below average in a lot of things. I wasn't great and I think the other thing was that even then I knew I was going to a good school and was messing up an opportunity, but I was a bit too rebellious. And I only went to Latymer because I got a free place there…. my parents could never have afforded it!

My parents wanted me to have a good middle-class office job and go to university. I really wanted to be a pilot in the RAF

My parents wanted me to have a good middle-class office job and go to university. I really wanted to be a pilot in the RAF

What kind of ambitions did your parents have for you at that time?

(laughs) Well, I think like most parents at that time they wanted me to have a good middle-class office job and go to university. You know, we couldn't afford it in those days and I wasn't anywhere near academic enough. That was one of the problems of that school. The minute they realised that you're not university material, then that's it. It's like you cease to matter to anyone. They'd say "Well, if you're not going to go to university, then go to the careers office". You'd go to the careers office and the bloke would be like "What?... Oh, banking!" and would just give you a form. You'd be like "Aren't you supposed to talk to me?" The funny thing was up until the time I was 14 or 15 I really wanted to be a pilot in the RAF (laughs). It's reading all those comics when I was a kid. I wanted to be Paddy Payne.

You're not the first person I've spoken to in the reggae industry who wanted to be a pilot. Little Roy said he wanted to be a pilot, he never wanted to be a singer.

Really? Well, he got about as far as I did with it, obviously. Yeah, the thing is it dawned on me that I wasn't academic enough and really I wasn't going to fit in as an officer in the RAF. I don't think I would have done very well at Cranwell.

When did you pick up a guitar?

I really wanted a guitar for Christmas when I was ten, I think. I got the guitar for Christmas, and it was quite good of my parents actually because they said "If you're going to have a guitar you'd better learn to play the thing properly" and they sent me to lessons at a music shop in the Angel. All I can remember about the teacher is that he used to chain-smoke, he just smoked incessantly. He taught me the rudiments with the help of the Mel Bay guitar tutor books. So I learned the basics of reading music, which I'm still absolutely dreadful at. I can read it very, very, very slowly but I still get very mixed up with it. I played guitar for a couple of years and then stopped when I went to the secondary school.

I got a guitar for Christmas, and my parents said "If you're going to have a guitar you'd better learn to play the thing properly"

I got a guitar for Christmas, and my parents said "If you're going to have a guitar you'd better learn to play the thing properly"

Why did you stop?

Because reggae started getting popular when I was 13 and my mates and I started liking reggae. The lead guitar in reggae isn't a particularly prominent thing, especially at that time, so I didn't really have any sort of guitar heroes to latch onto in the way that the more middle-class kids at that school were talking about Jimmy Page like "Oh, he was a session musician when he was 14". They could all play these tunes like Angie and Cocaine Blues and Albatross by Fleetwood Mac that didn't really interest me. I didn't have the drive to keep playing guitar and so I just stopped. It's a really odd thing that now I'll listen to some of those records that I loved at the time and think "That's a really nice bit of guitar - I wonder if that's Ranny Bop playing that?" or "That's a really nice Ranglin record from 1970" or "What he's doing there is really nice". But when you're a kid you don't listen like that, you listen to the whole thing; you're not being analytical about it.

What was the first reggae tune you heard?

I always really liked pop. I loved the Monkees, I don't care who knows that. Loved the Beatles, the Kinks, Small Faces, I liked Motown stuff. So I'd obviously heard records like My Boy Lollipop, the Johnny Nash records that were hits, Cupid, You've Got Soul, Hold Me Tight. I really liked Without You by Donny Elbert. I don't think it was a huge hit but I remember it being played. My best mate's older brother was buying records. He had those albums like Coxsone Special and Bluebeat Special and the one on Island, Put It On: It's Rock-Steady. And a little after that he had the first Tighten Up album.

I know I've told this story before, but I was round my mate's house one day and his elder brother came in with a couple of records in a bag. He said “I’ve been in this reggae shop in Kilburn". It was like "Fucking hell!" because in those days for a white kid to go into a black reggae shop, it was a bit of an undertaking. I just remember he played Mama Look Deh and me and my mate were like "What are they on about? Can't understand a word" but there was just something about the record that just really hooked me. Still one line where I've got no idea what they're saying. Funnily enough when I was interviewing Sydney Crooks later for Blues & Soul I said "What are they singing about in Mama Look Deh?" and he took me through the whole song. I don't know whether he skimmed over this line or whether I've forgotten it but there's one line where I've got no idea.

I always really liked pop. I loved the Monkees, I don't care who knows that

I always really liked pop. I loved the Monkees, I don't care who knows that

What was the first piece of writing you did?

Funnily enough I found it a couple of weeks ago but I'd be too embarrassed to show you. In the second year of school for a school essay I did a review of Tighten Up Volume 2. I'd never done any proper writing for anyone else until I did the thing for Blues & Soul. Me and John McGillivray were reading Blues & Soul - we used to look at the other music papers as well like Melody Maker and NME. If the music papers at the time printed anything about reggae at all it was just more or less a verbatim copy of the press release. There was no-one in there to say "Well, this record's really good but what about this record?" or "There's this pre-release come in from Jamaica". Me and John said if anyone was going to do a reggae thing it should be Blues & Soul. So we said "Right, we're both going to write in and see if one of us can get a column in it". Of course, like a mug, I was the one who wrote in and John never bothered. But they wrote back to me and they said "Well, if you want to give it a try. We can't pay you, but if you want to do it, then do it". So that's how I started. After about six months they said "This is all right. We still can't pay you but we'll give you some expenses". So of course I'd nick a few pounds on the expenses and plus I was getting the review records, so it was worthwhile and I really enjoyed doing it. I mean, I'd never claim to be even a good writer. I look back at some of those things and they're not very well written, but I like to think that I was enthusiastic and that gets across, and I used to put in pre-release charts and things like that. I'd review the sort of records that no-one else would ever mention. I do occasionally talk to people who say "Oh, I used to read your things in Blues & Soul. If it wasn't for that I wouldn't have known about this or that", so it fulfilled a purpose, which I'm quite pleased about.

When I spoke to both of you before, John said that there wasn't really anyone writing about reggae at the time. When did people like Carl Gayle and Penny Reel start?

This was long before Penny Reel. I think I started in '73. The first I knew of Penny Reel was when him and Nick Kimberley put that Pressure Drop fanzine together, and then I got roped in for the second one. That was when I met Penny Reel. I think before I started writing there was a bloke called something like Dalrymple Henderson. He’d written a little pamphlet and I think he’d written a couple of things for NME or Melody Maker, and I read that and I thought “I’m sure I could do better”. I don’t think he did it for very long. I never met him, and I never heard of him again. Carl Gayle had written a couple of things. Pressure Drop fanzine found this article written by someone and they reproduced it. It turned out to have been Carl Gayle, but there was nothing on the bit of writing because they found it in an office somewhere. But there wasn’t anyone else at the time doing it, and then Penny Reel came along; I think Nick Kimberley was writing. So while I was writing I did bump into other people who were interested. Plus my first job when I left school was working in Junior’s [Music Spot] in Stroud Green Road, which is where the Bamboo and Banana labels came from. That was where I met Tony Rounce and Dave Hendley, he took over from me when I left Blues & Soul and went to Black Music. I’m trying to think where I met Nick Kimberley; I might have met him there as well. Through Nick Kimberley I met Penny Reel, when they did the magazine.

If the music papers at the time printed anything about reggae at all it was just more or less a verbatim copy of the press release. There was no-one in there to say "Well, this record's really good but what about this record?"

If the music papers at the time printed anything about reggae at all it was just more or less a verbatim copy of the press release. There was no-one in there to say "Well, this record's really good but what about this record?"

Tell me about your first trip to Jamaica in December 1973 aged 17.

(laughs) That came about really because I was interviewing Scratch for Blues & Soul. Obviously you want to go to Jamaica, don’t you? I must have said something like “I must try to get to Jamaica one day” and Scratch, very kindly, very naively said “When you come you can stay with me”. He’d just been telling me about this new studio he was starting to build. I thought “Ah well, great. I’ll take you up on that” and I did. I booked the ticket for a charter flight. I wrote to Scratch and said “Is it all right if I come and stay with you?” and he wrote back and said “Yes, it’s fine”. That was pretty nice. So I went. The flight was delayed by a day or two because there was a big fuel crisis at the time. I landed in Jamaica at two o’clock in the morning and I ended up sharing a cab with about six other people. I was the last one to get dropped off and I thought “Ay-ay, this is it; this is the end of me. I’m just going to disappear now”. But the cab driver was really good and took me round to a couple of hotels that didn’t have room and I ended up staying at the Pegasus. It was a big, posh hotel in the middle of Kingston. I found Scratch at the end of the next day but it was too late to come out of the hotel, so I spent two nights in the Pegasus. I did half of my spending money just on those two nights.

I said "I must try to get to Jamaica one day" and Scratch, very kindly, very naively said "When you come you can stay with me"

I said "I must try to get to Jamaica one day" and Scratch, very kindly, very naively said "When you come you can stay with me"

How easy was it to find him?

Even finding Scratch, that was a flipping military operation. I woke up, left my hotel, walked down Orange Street, saw Bunny Lee’s shop, walked in there, said “Hello, is Bunny Lee here?” “No”. “Any idea when he’ll be back?” “He might be back later”. I had a walk round, came back: “Where’s Bunny Lee?” “He’s upstairs”. I went up the stairs round the back and we had a drink. He said “Where are you staying?” I said “I’m at the Pegasus at the moment but I’m supposed to be staying with Scratch”. He said “I’ll take you round there. I’ve got a couple of things that I need to get back”. I didn’t realise that Bunny Lee and Scratch are having some flipping war! So he’s taking me round Scratch’s with Blackbeard; I’ve gone in to see Scratch, Blackbeard’s come in and retrieved a couple of microphones that Bunny Lee’s lent Scratch or something. Bunny Lee isn’t coming in the house. Scratch’s missus Pauline is going off on one about Bunny Lee. Oh flipping hell, I’m right in the middle of it, you know?

A kid of 17!

Yeah! I had my 18th birthday when I was there, in the January. So the next day I moved round to Scratch’s and stayed there for just under a month. He’d just built the studio, and although it was January and there wasn’t really a lot of recording work going on anywhere, it was still nice to see what was going on. He took me round to see Dynamics and Federal, and Harry J’s. Went round Tubby’s a couple of times; that was really interesting. You know, just to see someone who’s got a studio in his living room. You don’t need a big purpose-built building, you just do it in your house. It was fantastic.

Bunny said "I'll take you round to Scratch. I've got a couple of things that I need to get back". I didn't realise that Bunny Lee and Scratch are having some flipping war!

Bunny said "I'll take you round to Scratch. I've got a couple of things that I need to get back". I didn't realise that Bunny Lee and Scratch are having some flipping war!

Who really made an impression on you out of all the people you met when you were there?

They all did really. A lot of them I’d already met and interviewed in the UK. That was great because everyone was really friendly. I had people like Tommy McCook and Bobby Ellis coming over and saying “Oh yeah, it’s great to see you here” and obviously Bunny Lee was great, Scratch was great, Keith Hudson was great. Keith Hudson said “Come down by my shop” and I said “All right, I’ll do that tomorrow”. He had this little shack down on South Parade, which is this big sort of roundabout thing. North Parade you had Randy’s and Joe Gibbs’ shop. All round the parades you had these little shacks selling all sorts of stuff. I went round there and he said “Let’s go to the beach”. We went down to this beach, just behind Bellevue, sitting in this shack with these dreads and Keith Hudson rolled this huge ice-cream cone sized spliff. I thought “Oh, he’s going to have some fun with that!” and then he’s gone “Here…” and it’s for me. I thought “Hell”. I’d sort of tried it but I don’t really get on with smoking, it doesn’t suit me. Anyway, I got through half of this spliff and I was off my nut, I could hardly stand up. It was time to go and I remember we went back and I’m just thinking “I’ve got to get out of here, I’ve got to get out of here”. I said my goodbyes to Keith, I came out of the shack, turned right, went about ten yards and then I sort of woke up sitting in the gutter at the side of the street. I’d passed out but not fallen over, just sort of sat down.

Just crumpled.

I thought “This really won’t do”. Some sort of skinny white kid in the middle of Kingston, off his nut. I got to my feet, hailed a cab, fell into this cab and went up to this hotel Green Gables, which on subsequent trips we used to stay in. Opposite this was a McDonalds, but not an American McDonalds. Jamaican-style, they’d just nicked the name. Hamburgers were really, really nice; 100 times better than any McDonalds hamburger. Really nice hamburgers, really nice chips. I thought “You know what? I’m hungry. I need some food”. So I was sitting down having hamburger and chips and Niney and Chinna came along. They said “What have you been up to?” and I told them. They said “You shouldn’t smoke that stuff on an empty stomach!” I was like “Yeah, now I know!” (laughs). That was an experience.

I got through half of this spliff said my goodbyes to Keith Hudson, I went about ten yards and then I woke up sitting in the gutter at the side of the street

I got through half of this spliff said my goodbyes to Keith Hudson, I went about ten yards and then I woke up sitting in the gutter at the side of the street

When you came back did you look at or listen to the music differently?

That’s an interesting question. I’ve never really thought about if I looked at it differently. I might have looked at it a bit more analytically because I’d been in a couple of studios so I’d seen how tracks are split up on the tape. I sort of understood how dub records worked anyway but actually seeing someone mix a dub and do stuff with it, you think “Oh right, that’s how they do it”. It probably just strengthened my resolve.

It wasn’t like a Damascus moment.

I didn’t have any sort of epiphanies; I just got more deeply into it. I didn’t even see any sessions where rhythms were laid. I saw Chinna, I saw Winston Wright doing overdubs. I saw Bob Marley sing a couple of tunes. I saw Horsemouth and Ansell Collins do Herb Vendor, and I saw Delroy Butler voice the tune Give Thanks that’s on the other side of that. I saw Earl George, who was later to become George Faith, do his first version of To Be A Lover. I hate that rhythm so much, I heard it for two days straight and nothing else. God Almighty. If I never heard that rhythm again, I’d be happy. It was number one as well, because Have Some Mercy by Delroy Wilson was the number one tune at the time, that and Here I Am Baby by Al Brown. When Bob Marley was in Scratch’s studio, I even contributed a couple of lines to one of the tunes that he did. I put in a line on one of those Leo Graham tunes. I loved that idea of everyone just sort of sitting around and vibing up. The singer’s like “I’ve got an idea for a tune” and singing it and then Scratch would say “Oh you could say this, you could say that”. You get carried away with it and you start putting in rhymes yourself. When one of them gets accepted it’s like “Oh wow! I’ve co-written a song!” Seeing that part of the creative process and Scratch was saying “See how here on these machines I can drop in” and seeing how when the singer makes a mistake you can go back over and correct that mistake without having to do the whole song again. Those little technical things were interesting.

Did that draw you to engineering?

That probably drew me into the technical side without me even really knowing it. I’ve said this before and I know it’s very arrogant but I used to listen to tunes then and think “Oh blimey, I don’t like the way he sings that line there. He could have sung that better” or “Why didn’t they bring the horn section in earlier”. I supposed they’re production points but I just thought “This record could have been better if they’d have done that”. The other thing is I am very critical. There were records that people used to bang on about and I used to think “Well, I don’t think it’s that good”. Especially if it’s like the third deejay piece to a particular rhythm, you know? I’d be going “The Big Youth’s really good and the I-Roy’s really good, but do you need A.N. Other chipping in with his version, when it’s not really saying anything that improves it?”

As time went on, did you get fed up with the writing side of it or were there lots of things going on at the same time?

Yeah, I got fed up because I never used to like the writing. I used to like the interviewing, I used to like hanging around in studios, meeting my heroes, like any sort of young kid does. But actually sitting down and having to crank out a thousand words or something, I found it hard work. I know people are going to say they found it hard work to read them, but believe me I found it very hard work to write it sometimes. Funnily enough I just did some sleeve notes for a Japanese company the other day, and I actually quite enjoyed doing that, possibly because it was the first time for quite a long time. I think it’s a bit like DJ-ing, you know, I like DJ-ing but I couldn’t do it every week. I couldn’t even do it every fortnight; it would drive me round the bend. But it’s nice to go out and do it once every couple of months. The writing’s the same thing; if it’s something I’m interested in and I can think of things to say about it… I don’t know how you find writing. Perhaps for you it just flows out and you find things to say, but quite often I’d just be drumming on the top of the table, thinking “Oh, what can I say about this?”

I never used to like the writing. I used to like the interviewing, I used to like hanging around in studios, meeting my heroes, like any sort of young kid does

I never used to like the writing. I used to like the interviewing, I used to like hanging around in studios, meeting my heroes, like any sort of young kid does

Was there pressure on the financial side of things?

No, I was working. I’ve always had proper jobs. When I was writing for Blues & Soul, Black Music, Melody Maker; that’s always been on top of something else. I’ve had loads and loads and loads of jobs, doing all sorts of stuff. I never, ever looked at the writing as anything near a full-time thing, I just looked at it as a hobby that when I did start to get properly paid for it, get union rate and so on, well that was nice, plus you get all the free records, plus you’re doing something that you really enjoying and you’re meeting people, although some of them are not as nice as you’d hope they would be, but they’re all human beings so you have to take the rough with the smooth.

What was the worst job you ever had?

I was a milkman for six weeks. Really didn’t like it. Because I used to like doing ‘job and finish’ jobs. At one time John and I both worked at Young’s Brewery in Wandsworth, we were draymen.

Didn’t Rodigan work at a brewery as well? He worked at the one in Chiswick, I think.

Oh, at Fuller’s? It’s not very good beer, is it? Not as good as Young’s was! The thing with being a milkman was that if you had an easy round and you could run it, then you’d get it over and done with. But the trouble is, once they saw that you were finishing the round early, they started putting other bits onto you. They’d say to you “But you’ll get a bonus” and you’d think “Hang on! I’m doing another hour’s work here for nothing”. The bloke who used to have the round that I’d got, which I was just starting to get under my belt and get used to the idea of it, he wanted the round back because the round he’d been given was too hard, so they gave me his round and it was fucking murder! I did it for about four days and said "You know what? I can’t do that”. In those days you could walk out of a job and you’d get another job the next week. I did have loads and loads and loads of jobs.

When you were doing Fashion were you still doing some writing from time to time?

I think I was still writing for Black Music then. I can remember I went to Birmingham to interview UB40 in the producer’s house studio where they’d done that first single; he’d got a sort of 8-track studio. They said to me they were going to do an album and they wanted to go to a proper big studio in London. I’d just done the first tunes with the Investigators as The Private Eyes, for Dave Hendley’s label in a studio called TMC, Tooting Music Centre, in Tooting. I said “They do a lot of the lovers rock stuff, the Investigators use them all the time, the engineers are really good” because to get a studio where they actually knew reggae was a big hurdle in those days. I’ve done it, I’ve gone in studios where the engineers, no-one knows anything about reggae and everything just takes too long and you end up with something you don’t want. So I said “Go to TMC” and when they brought out that first album, where did they record it? TMC: The Music Centre, Wembley, which is some huge, huge big pop studio. I thought “Well, you never listened!”

As you got immersed in the engineering and the music side of it, what did that do to your writing, if anything?

I think it just made it harder. I remember getting fed up with the writing and just thinking “Pfff! I just can’t be arsed to do it anymore”. I think the other thing was because I’d always written from a very grass roots level, I wasn’t really that interested in promoting the latest pop reggae tune and I never really did the mainstream reviews, even when I was writing for Melody Maker. I was always doing the reggae page or the reggae column. My memory of that time is that I just found the writing more and more laborious and got fed up with it. The mainstream journalists were getting treated to trips to Jamaica and all this sort of malarkey, and I was a bit “Well, hang on! I was writing about these people years ago and I ain’t getting none of that”. Really I think I was just getting more and more interested in just making music and less and less interested in writing about it, especially as I found it hard work anyway.

The mainstream journalists were getting treated to trips to Jamaica and all this sort of malarkey, and I was a bit "Well, hang on! I was writing about these people years ago

The mainstream journalists were getting treated to trips to Jamaica and all this sort of malarkey, and I was a bit "Well, hang on! I was writing about these people years ago

I think especially if you’re having to do various different jobs then you’ve got to sit down, this is the time you’ve got and you’ve got a deadline. It’s not like you’re someone who’s getting up in the morning, looking out the window and thinking about what you’re going to write.

(laughs) Yeah, I’ve never had that luxury! So I just got more and more into the music. The thing was that when John and I started Fashion, I had done this thing for Dave Hendley and his partner, this Cruise label thing, and they did all right. John said “Me and you should get back together” because I’d left Dub Vendor previously, I thought “Yeah, that’s a good idea”. So when we did Let’s Dub It Up and It’s Too Late and got off to a very good start with Let’s Dub It Up, I realised that this was something I could do, and I enjoyed it. I know it’s the same thing as when you write something and then you actually see it in print in the magazine, and it’s got your name at the bottom and that’s fantastic. But making a record and hearing it played on the radio, going into a club and hearing it, even seeing it on the label and seeing people buying it in a shop, it’s just so satisfying.

I used to live by the river and in those days you would get sound systems come along on boats, and I can remember lying in bed hearing Let’s Dub It Up, Swing and Dine, things like that, pumping out from these boats at 3 o’clock in the morning, thinking “That’s my tune!” It’s a great feeling. Even better if you’re the singer and it’s actually your voice; that must be the greatest thing in the world. So I went from something that I sort of enjoyed to something I enjoyed a lot more.

Read more about this topic

Read comments (4)

| Posted by Guillaume Bougard on 03.25.2013 | |

| FAN-TAS-TIC Chris, we need a book from you |

|

| Posted by Dubba on 03.26.2013 | |

| +1for a book! | |

| Posted by Angus on 03.27.2013 | |

| You'll enjoy the first question of part 2... | |

| Posted by Dubba on 03.28.2013 | |

| Looking forward to it, keep up the good works Angus, always look forward to reading your articles. | |

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z