Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Earl 16 (2014 - Part 2)

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Earl 16 (2014 - Part 2)

Interview: Earl 16 (2014 - Part 2)

"They had all this vibe going on in England. It was like the new Jamaica to me"

Sampler

Read part 1 opf this interview.

In part two of our exclusive interview with Earl 16 we ask him about some of the hitmakers and legends he rubbed shoulders with as the 70s became the 80s, how he settled in England and his views on the state of the music today…

You’ve talked about Hugh Mundell and Addis Pablo. What was Augustus Pablo like?

Pablo was cool. He kind of got a little bit grumpy in the later years; I suppose because he had this bad illness, I think it was cancer. It was really sad. Pablo was so nice, so genuine. All of us used to just go round and hang out with Pablo because just the vibe, the spirit that he generated was awesome. He would just reason about roots, about Rasta; cook, everybody would just eat, have a smoke. He was always a guy who was trying to get away from the city, always close to the river, always living somewhere nice in the countryside. So you need transport to go and see Pablo. I was always around him because there was a guitarist that used to literally live with Pablo at one point called Fazel Prendergast, who used to play for Mutabaruka. I used to go there, spend the night, wake up the next day, go to the studio.

All of us used to hang out with Pablo because just the vibe, the spirit he generated was awesome

All of us used to hang out with Pablo because just the vibe, the spirit he generated was awesome

Pablo for me was very eccentric. He was a guy who rarely slept. He was a guy a bit like Boris Gardener, recording, always practising, always on the keyboard as soon as he’s awake. The thing about Pablo, before he was a melodica player he was one of the best rhythm musicians in Jamaica, he used to be a session musician that played for different producers: Leslie Kong, Dynamics, Federal Records; he could chop the piano so wicked man! He was one of the top musicians that we had. He started his own label and the little sound system and stuff. We were just there to support him. A lot of the guys now, they’re planning to do like a rockers showcase, like Ricky Grant, Norris Reid, Delroy Williams is hopefully coming over this summer to do a tribute to the whole rockers family thing.

Winston and Pablo were friends with Jacob Miller - were you?

Yeah, in a small way, not a big way. We used to hang out at the studio and stuff. But Winston was a big friend and Winston used to go to the house in Beverly Hills and all that. I met Jakes a couple of times in the studios but I’ve never actually seen Jakes perform live, which is one of my regrets. I really wanted to see him because he was such, such great energy. They used to rehearse a lot in New Kingston at a place called Zinc Fence. Third World used to own it. So all the musicians would come there to rehearse when they were going on tour or something. But Jakes was nice, the only problem I had with Jakes was he used to smoke the high-grade a lot and he used to slag me off. He used to say “Sixteen, you must stop smoking cigarettes. You smoke too much cigarettes” because I don’t know how long I’ve been smoking and I’m still doing it, I need to stop actually. Jacob was one of the top guys, man. Such a beautiful guy.

How much contact did you have with Bob Marley?

I met Bob a few times. We used to hang out with a friend of mine, Richard McDonald who used to bring me there. Richard Mac was one of the top singers for Alvin Ranglin, which was GG Records. Bob was a good friend of his so he used to sometimes rehearse if the group wasn’t there, if the I Threes didn’t turn up, I used to go and sit in on the rehearsals. I kind of just knew Bob when he was in Kingston at Harlan House, then we used to follow him to Bull Bay in the mornings to go jog and stuff. He used to go jogging literally every morning, from five o’clock in the morning Bob is down there on the beach, running nine miles – that why it’s called Nine Mile, it’s nine miles of beach (laughs). Bob was cool. He used to swear like a trooper, he could cuss some, that man! Every other word was a bad word. But he was sweet, man, he was sweet. Bob was like Joseph. He was a man who used to give so much. He used to always, when he came back from tour, used to sit under the big mango tree in Tuff Gong, Hope Road and all these people would join the line and Bob would just be giving out $10,000, $20,000: “What’s wrong?”, “Oh my baby need some shoes”, $10,000. He was amazing. Every month he’d do that. I couldn’t believe, I’d never seen something like that. It was like I was back in the days of the Bible, you know? When one of these prophets was giving out corn, giving out some wheat because there’s a big famine or something. It was amazing. Bob was cool.

Bob was cool. He used to swear like a trooper! Every other word was a bad word

Bob was cool. He used to swear like a trooper! Every other word was a bad word

You were also very close to Junjo Lawes but you never recorded with him.

Junjo Lawes used to live on almost the same avenue, we used to live close on parallel streets, I used to go round there and hang out with him while they were building the sound. He was always asking us to “Go and book some studio time for me, go and play with some guys for me, blah-blah-blah” so I wasn’t really doing music with him, just helping out the production because he was doing everything on his own. This was late 70s. Just when Barrington Levy was there. I was one of the kids who went and got Cocoa Tea for him because he heard Cocoa Tea was doing really good and he wanted to get Cocoa Tea from the country and I had a motorbike, so I used to ride and go and pick up Cocoa Tea in the mornings, bring him to Channel One, that kind of thing. So I used to be just like an errand guy for Junjo because he was such a good friend of mine.

How come you didn’t sing for Junjo when you were that close to him?

That’s a very interesting question. I thought we were so close mate, you know? I was with his mum, I was with his wife, every day I was looking after Chris Cracknell from Greensleeves, he came down a few times. I don’t know. Because I was just one of the guys who used to help Junjo with the studio. He used to give us the money to pay the musicians, he used to give me a car trunk full of money and say “Earl, go and pay them”. At the time the pace was too hot, man. You had people like Yellowman, I think Yellowman at one point voiced ten albums straight for Junjo, for a car. Then you had Eek-A-Mouse… it was just so exciting for me, you know? I forgot that I was singing, man! (laughs) I wanted to be able to be in the studio with these guys. In the meantime I was still involved with working with Studio One, I was working with Linval, I was kind of working doing my own little thing. With Junjo it was a different experience because he was like a big brother to me, so I was just helping him out because he had so much iron in the fires. He had so much things doing – there was building the sound, there was working for one of the MPs or councillors in the area as well, so he didn’t have much time in the studios.

For a lot of the veteran artists I interview Studio One figures at the beginning of their careers. Whereas when you had a couple of big tunes at Studio One – Love Is A Feeling and No Mash Up The Dance - you had voiced for many other producers and Studio One wasn’t quite the dominant force that it was.

I used to have a little motorbike, and I used to go from studio to studio and what I noticed was when you’d got to Channel One I was licking some great rhythms and Sly was fantastic, but most of the tracks were Studio One’s do-overs. Joe Gibbs was the same. I thought “You know what? I’d like to sing on the original”. Because then, when you’d go to Studio One there was no-one there, just Coxsone on his own, having some rum, getting some tapes out, doing some repress and stuff, so it was cool! I could go in there and I’ve done more than two albums at Studio One. I don’t know what’s happening. I must ask his daughter if she can find the tapes. Barry Brown as well did a few big songs at Studio One but people had kind of moved on from Studio One in the early 80s, coming into the mid-80s, the era changed and it was more dancehall style. The whole music genre had kind of moved off from rocksteady and ska and stuff. So Coxsone started to get all his kids to come and overdub on some of his old Studio One rhythms. That’s where Steely and Clevie came in.

You didn’t actually start putting out albums until the 80s. You recorded two albums with Roy Cousins.

The Cousins things were literally straight after the Coxsone, around ’80 or ’81. I was there at Coxsone doing some work when Roy came, because he did some tunes with Coxsone, and he heard my stuff and he was buying records to take to England, bringing vinyl back and forth. That tune Love is a Feeling we were selling and he called me to one side and he said “Sixteen, bwoy, I could get you some money if you do an album because your tune is doing good in England”. So I went and did a little album called Julia or something like that. I used to hear though, because now and again we used to get a thing called the Black Echo magazine and you’d see the charts and artists and interviews. They had a nice big front page with maybe the top guy at the moment or something. I was like “Yeah man, I want to go to England and start up!” But to be honest in Jamaica a lot of us wasn’t really interested in England because we heard “England cold, it’s wet, it’s foggy” so we all wanted to go to America or we wanted to go to Canada. Canada was big for reggae during the 80s. They had a big reggae scene over there. I’ve been to Canada a few times as well.

Then you recorded Shining Star which was produced by Earl Morgan from Heptones.

Yes, Earl Morgan, Earl Heptone. Which was released by a guy called Victor Records, one of the top record labels in England. At the time Roy was kind of lacking, he was coming and hiding out, we didn’t see him when he came to hang out with Jack Ruby. It was cool working with the Heptones because those guys were huge at the time. Some of the rhythm tracks that these guys had, they used to get them from Tubbys, they used to buy them from different producers around the place. At the time I had a few tunes that were playing a lot in England, so everybody wanted me to voice a tune. There was me, there was Barry Brown, there were a few artists, young upcoming kind of people, Anthony Johnson as well, he had that little Gun Shot tune going, Michael Prophet and that. So yeah, it was kind of busy voicing so I can’t remember the exact time, but I think Roy Cousins was before and then the Heptones thing. And then the Mikey Dread album.

So where does Linval Thompson and Channel One fit into all of this?

The Linval Thompson project came in around the same time when I was doing the Earl Heptones thing. Linval himself had just put out an album called Look How Me Sexy or something like that, smashing up the place and getting lots of money. Because I was always at Channel One, always with Junjo Lawes, he said to me “Look, I’ve got some rhythms, I’d like you to do something”. He gave me the tape, gave me some money, and asked me to go to Tubbys and voice them. So I went and voiced them and then he just came up to England and Trial & Crosses, Blackman Time, about three or four songs I did for Linval.

So what happened with the Mikey Dread album – Reggae Sound? It didn’t do well.

The Mikey Dread album, I think it was released over here but Mikey was in the middle of launching his career as well. He came over here and he got kind of stuck, people wanted to do some different things with him, so he put the own label thing on hold for a bit because he’s a radio personality first and foremost. He was producing myself, Edi Fitzroy, a kid called Sunshine, Rod Taylor, he had a lot of good stuff in his catalogue but he also had a career. Also, he wanted to bring me to England but I think I wasn’t ready to come to England, I wanted to go to America. So I think he brought Edi Fitzroy instead. So the Mikey Dread album, I didn’t think it generated that kind of vibe because he was busy doing other things. He’d started hooking up with the Clash and those people, and I wasn’t really here to help promote it. But during the 80s Mikey brought me to California and we were doing some serious university shows and stuff, so eventually I came to England with him, did a few shows in Europe, in France. Winston McAnuff was one of the first guys that brought us to France because he had his little band called the Black Kush band with his brother Tony McAnuff, some brilliant musicians he had with him as well. We did a tour – three months we spent in France. That was really strange. I think 1985, ’86.

Let’s talk about you going to England in 1988. Why did you make the move?

I was in America doing a tour with a guy called Stafford Douglas, a promoter from Birmingham who had a label called Mafia Tone. I used to work with Mafia Tone a lot. He went to do a tour with Tenor Saw because Tenor Saw had just done a big hit album Ring The Alarm. I was in America touring with Cocoa Tea, Bammy Man, a few of us. The guy called us up and said “I’d like you to come and help me out with this show” because Tenor Saw wanted so much money that he couldn’t really afford to bring a next “big act” like a Dennis Brown or anything, so I said “Yeah man, I’ll do it”. Oh man, the tour was awesome! Not a big tour, we did three shows – one in Birmingham, one in Acton Town Hall, and I think we did one in Wolverhampton or somewhere like that. I had been over before in ’87 with a woman who was doing a show at the Albert Hall – Ken Livingstone had a show called Great London Council, the GLC. The GLC had sponsored about fifty artists who came from Jamaica. There was Leroy Smart, there was me, Anthony Johnson, Sassafras, oh man, about twenty of us were on the plane to do a show for GLC. I got two weeks stamp in my passport, I ended up staying for about six months and they said “Right, that’s it. You’re never coming back to this country!”

Unbelievable! So Margaret Thatcher got rid of the GLC because they were doing things like this!

Yeah! Big reggae show in Queen Elizabeth Hall it was, the first time I came to England. That was the first show I did and I was like “Wow!” Couldn’t believe it!

No wonder she tried to get rid of them.

Telling you! GLC was keeping some serious dancehall shows, man. Believe me, really supporting some dances, man! That package was crazy. A lot of us were staying, hanging around. Anyway, I had a really good time with those guys from Birmingham. The guy had a big sound system and he brought me back up and I started doing a lot of shows. I met [Lloyd] Coxsone, I met Mad Professor, started doing some recording. But the main reason that I came was to do that tour with Tenor Saw, with Mafia & Fluxy – the band was called Instigators. It was a wicked band. I was so impressed because around that time the bands in Jamaica, the whole live music scene was kind of going down because the sound systems were so strong, you know? There were all these big sound systems like Gemini, Metro Love, it was getting so live music wasn’t so much. But when I came to England during the 80s, wow man! There was an abundance of bands. There was Aswad, Steel Pulse, all these bands, you know? I really liked it and I was hearing music that I wouldn’t be hearing in Jamaica anymore because they had loads of pirate stations – you had Tony Williams, you had all these guys, you had Ranking Miss P, it was crazy! I was hearing tunes that “Wow! I didn’t hear it in Jamaica for donkeys years” so I kind of fell in love with England after a while.

Ken Livingstone and the GLC was keeping some serious dancehall shows

Ken Livingstone and the GLC was keeping some serious dancehall shows

I settled down, settled in for a little while and once I started working with Mad Professor and all these guys I started going out into Europe. In ’92, ’93 we started venturing out to Europe with Macka B and all these guys to small little festivals like Loreley festival with 3,000 people, which is now Summerjam. Mad Professor used to go to these strange places and I’d be like “Prof, we’re the only black people in the whole of East Germany. What are we doing in fucking East Berlin, blood?” Before the wall came down we went there with Yabby You and these guys are singling some hardcore reggae music and I’m thinking “Oh man, if I don’t go back home tomorrow I’m going to get…” because you know, it’s really dangerous! UK was like the power-point of reggae music in the early 80s, late 80s, for the whole of Europe. There wasn’t even that much sound systems in Europe and England had Coxsone, they had Saxon, they had Fatman, you know what I mean? They had all this vibe going on in England. It was like the new Jamaica to me, man. I was happy!

What do you think happened to the UK scene? It fell down just as the Europe thing started to get really big.

I think that the people in the business, here in the UK, started to lag a bit. They were like “I’m the king, I’m the king of Europe so I can relax for a bit” and then you had some young little kids in Germany, in France playing just like Ruff Cut. So you found that a lot of the musicians weren’t getting so much work anymore because the kids in Europe would be able to back for Culture if Culture couldn’t bring all of his guys from Jamaica, he could get two guys from Germany and they would be just as good.

Also I think that when I first came to England there was so much reggae magazines, you had the reggae chart, reggae had a home, a place in the whole media thing; then the magazines started disappearing, there was no more reggae chart in ’95, ’96, JetStar was falling down a little bit as well and wasn’t doing so much. There wasn’t as much support for the up and coming British artists as well. I’m a Jamaican artist but I loved the British artists. I love people like Maxi Priest, Barry Boom, Trevor Walters, all these guys that were coming up. There wasn’t a lot of support. If they weren’t with Island Records or Virgin the support wasn’t there, and once a major label took up an artist they became really too commercialised. It’s kind of like the whole thing got too commercialised, so it was only the sound system that was left here in England that was really holding the vibe.

Because even now I’m doing a show this weekend with Mad Professor and Addis Pablo and it’s in a pub! I mean you go to Europe and you’re doing a show and it’s in a big old venue or a proper club. In England there were so much clubs back in the 80s, in Bristol, in Birmingham, you’d go to all these nice little places. All of that has disappeared because I suppose with all the drugs, the gang thing, you know in the late 80s this Yardies and all this gun kind of thing came into the UK, which is not something that they’re used to. All these gunmen started hanging around reggae musicians and artists and also made it bad, shooting up the dances, so we started to lose venues because the promoters were scared that if they bring an Elephant Man or a Beenie Man to the dance it’s going to go mad, it’s going to go crazy! (laughs) I think also the music content that was coming after Bob Marley passed away, after Luciano came through, Beres Hammond and all that, then you had this kind of bashment business and I think that just put the nail in the coffin for the UK.

You worked for a lot of different production houses and sound systems. You’re happy to be on some big, heavy steppers thing, then you can be on some more light soulful rhythms. So long as it gives you a chance to have your messages on top, you don’t seem too partial about that.

In ’92, ’93 when I first started working with Mad Professor, Mad Professor introduced me to some guys, Paul Daley and Neil Barnes who had a little label called Leftfield and they wanted me to cover one of my songs Trial and Crosses. I went a voiced it with them and the rhythm track that they’d made it with was something called jungle, drum and bass. During that time, early 90s, there were these guys like Rebel MC and Double Trouble, they were doing all these tracks with like Barrington Levy, Supercat, just voicing, using samples of the voices, using some old bass and jungle was fast and furious! It was really popular, it was taking over – people going to raves and just listening to this jungle music all night. To me it was kind of like reggae but for a more modern era, a more futuristic kind of vibe. Then also the message was still in there. The BPMs were not too far, it was just the jumps that were more speeded up. It was really interesting. The Leftfield guys that I did that track with, from there you had Massive Attack come along and took it to another level, they did a track with Horace Andy, it just kind of went in a spiral. You had people like Prodigy who sampled Max Romeo. It was crazy! It was kind of cool. It was like an upliftment on the whole reggae scene. Then you had people like Lee Perry who came in and started working with Adrian Sherwood…

Jungle was kind of like reggae but for a more modern era, a more futuristic kind of vibe

Jungle was kind of like reggae but for a more modern era, a more futuristic kind of vibe

And Mad Professor as well.

Yeah man. To me it was like I was home now, because Mr Perry’s in town. I’ve kind of realised that because coming from a background as mine I used to sing with a band that used to play in the hotels, I listened to all various kinds of music, so to me it was all right.

You’d never been someone to say “No, this is the limit. This is reggae and this is not”.

Nah man, of course not. So I was cool to do it. I mean I wouldn’t want to do a rock tune, I wouldn’t be too happy to go and jump and do something with Ozzy Osbourne or something like that (laughs).

Recently reggae has been played on the radio in Jamaica a bit more than it used to be but also at the same time, in the last few years there’s been a lot of complaining from Jamaica that “brand Jamaica” being copied by other people from foreign places.

As far as the radio thing is concerned, the thing about Jamaica and the whole Caribbean and South American area, if you want stuff played on the radio, you pay money, man. You go and you pay the radio DJ and if it’s a good song he’ll play it because it’s just a money thing. If you got the more money you can get this thing going. I remember Bob and people like Leroy Smart and all that, they used to have to go and beat up the guys at the radio to play the tunes. Bob used to have to literally threaten “Look man, if you don’t play my tune, because my tune is good. I’m giving you a tune like Cold Ground Was My Bed Last Night or No Woman No Cry, and you don’t want to play it. You prefer play some deejay tune and some ting” but you know, it was like that.

So now I think a lot of the DJs are starting to get more encouragement from the producers. Most of them in Jamaica now just come back from America with a lot of money, or most of them still live in America but they support the thing a lot. They want to get certain artists, they want to get the Mavados, they want to get all the hype artists. There’s a lot of money flowing through the business now in Jamaica because a lot of the deejays, the young rappers like Popcaan or these young guys coming up, they’ve got a lot of influence on the American scene.

If you notice, Jamaica’s like a state of America. It’s becoming like a literal… it’s almost like you’re in America, I mean you can spend US dollars in any shop, you might have to go and change your pounds and your euros but they’ll take US dollars. Jamaica is cool but we’ve kind of lost the whole kind of analogue feel that we used to have in the productions and the recordings, and I think that’s where a lot of the Europeans have been cashing in. A lot of the guys now in England, all these guys like Steel Pulse, a lot of the bands they’re still doing the analogue. Mad Professor, Prince Fatty and Hollie Cook, all analogue. They maintained that analogue thing and it’s working for them. I don’t see the reason why it can’t work in Jamaica but Jamaica likes the higher up, like the rap thing, the fast lane kind of thing.

Jamaica is cool but we’ve kind of lost the whole kind of analogue feel

Jamaica is cool but we’ve kind of lost the whole kind of analogue feel

Final question, you’ve been quite vocal in criticising people pressing up and selling your music at dances recently. It used to be that no-one really minded if someone was selling some tapes at a show back in the day because that couldn’t be duplicated to the level it can be now…

Oh man, that to me is one of the downfalls of technology as far as reggae music is concerned. Reggae was a very authentic kind of thing. We used to have really great sleeves, artwork, designs were so fantastic, That was one of the things that made reggae so exceptional like Bob Marley’s album with the lighter, what do you call it?

Yes, Catch A Fire with the gatefold sleeve.

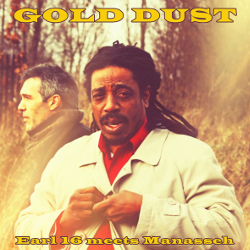

That was phenomenal, everybody spoke about that. Some of the sleeves that Coxsone used to come out with, with two guns and all them guys, I think Jimmy Cliff used to come out with a cowboy hat. The artwork and the design and stuff and also the dub and the music itself was very organic and original. Now you can release an album without even putting a vinyl, you don’t have to make a sleeve. I’m now putting out an album that I did with Nick Manasseh called Gold Dust, with Roots Garden and a label called Kudos which is like a downloading site. I was saying “So John, I’ve got to make a stamper, I’ve got to make up a sleeve” and he goes “No, no, no. You don’t need none of that anymore. We’re just going to put the album out, you just have to give me a small little sleeve, give me a nice picture with you and Nick” and that’s it. You don’t have to put a picture on the back or a bio or a barcode, so I’m really kind of reluctant about doing that kind of stuff.

That was phenomenal, everybody spoke about that. Some of the sleeves that Coxsone used to come out with, with two guns and all them guys, I think Jimmy Cliff used to come out with a cowboy hat. The artwork and the design and stuff and also the dub and the music itself was very organic and original. Now you can release an album without even putting a vinyl, you don’t have to make a sleeve. I’m now putting out an album that I did with Nick Manasseh called Gold Dust, with Roots Garden and a label called Kudos which is like a downloading site. I was saying “So John, I’ve got to make a stamper, I’ve got to make up a sleeve” and he goes “No, no, no. You don’t need none of that anymore. We’re just going to put the album out, you just have to give me a small little sleeve, give me a nice picture with you and Nick” and that’s it. You don’t have to put a picture on the back or a bio or a barcode, so I’m really kind of reluctant about doing that kind of stuff.

I’m from the old school. I’ve got my own little label Merge Productions, I keep pressing up my own little songs. My last album I pressed which was from Nick as well, Walls of the City. I did a nice sleeve, nice covers. It costs you a few grand. So when you have that and a guy comes along and he buys a copy of the record, first thing they do is put it on YouTube. I mean I’ve got a YouTube account but I wasn’t really interested in putting my stuff on YouTube unless it’s a proper video. That’s why I distinctly wanted to do just vinyl because I think that the vinyl takes a little bit longer for them to rip. If you put out a CD, certain shops now have stopped buying CDs because they’re saying it doesn’t sell.

All the rare vinyl tunes that have gone up on YouTube have kind of killed the excitement of vinyl too.

Killed it, because all that all that nostalgia has gone out of it. It’s not nostalgic anymore. You can find it on YouTube, you can download it, you can make your own copy. People will collect music, they don’t want to know about YouTube, they don’t want to know about CDs or who’s copying that. It’s personal, you come in and you have some time off at home and you want to play your records, you go to Jamaica and you pick up something, you don’t want to have everybody playing them, you know what I mean? It’s personal, it’s your favourite. It’s good to promote people who are just coming into the business, artists that’s just up and coming.

Doing a free mixtape that everyone can share.

Yeah, you do your mixtape, you give it away for free because you’re trying to get promoted. But artists like Dub Judah, artists like Twinkle Brothers, they don’t need those things, they work hard. Twinkle Brothers work hard, every year they put out two or three albums, I don’t know how he does it. Then you have some little guy coming to a dance with some CDs and flogging them for £5 and then he packs up and goes up. And it’s embarrassing, sometimes the production is so rubbish as well. It makes you look bad, people thinking “Bloody hell, that artist’s going to the dogs” because of how they copy it.

The quality of the files is often low so the production values are all lost.

They just don’t care. It’s sad, it’s sad at the moment. Now I’m really, really worried, but the good thing is for some of the artists coming from the era that I’m coming from, the late 70s, 80s and that, now is a time I’m doing all these shows. The sound systems, live shows, everybody’s calling up.

Because your voice is good.

My voice is still there. It’s fantastic, it’s amazing. I mean I’m going to places… in a few months I’m going to Chile; I’m supposed to be going to Thailand with Mad Professor and Prince Fatty. It’s mad. Some places that I thought I would never even dream of going but because the music is still there, is still going, people still recognise the old Studio One. I mean Johnny Osbourne, Johnny Osbourne’s taking the scene by storm. Nobody used to be really interested in Johnny Osbourne back in the 90s, they used to like his songs, but shows…

He can travel now, he only recently got the chance to travel.

Yeah, he got stuck with that visa thing. He was stuck in America for years.

People still want the vinyl. It’s hard to access it

People still want the vinyl. It’s hard to access it

Now the floodgates have opened for him (laughs).

Oh my days! I’ve seen him in Brazil, I’ve seen him in Japan. I can’t keep up with Johnny anymore! (laughs) Cornel Campbell, all those artists from that era. It’s amazing. I think I saw you at the Cornel Campbell show. I was so amazed… the songs, the band. I mean the band is a European band. It was wicked!

Soothsayers.

To me the show was like being in Jamaica in one of those old dancehalls watching a live show. It was brilliant and I think that’s one of the things that’s kind of keeping the business going. The live shows, Morgan Heritage and all these guys, Alborosie, that’s the only thing that’s keeping them going. Even if you run a studio. Record shops, you can’t find a record shop anywhere. I’ve just come back from Italy, I did two shows in Sicily and Napoli, and I was asking everybody “So how do you guys know the reggae artists? Know the tunes? Do you have a record shop?”, “No, we haven’t had a record shop for years”. I’m like “So how do you get the music?”

I brought some vinyls and people bought them like “Oh yeah man! Give me some of this, two of that”. They need it. People still want the vinyl. It’s hard to access it. A lot of people refuse to take the chance, you have to open a shop, pay the rent, and you don’t know how it’s going to go. Dangerous! It’s dangerous at the moment. It’s so bad. And people like Mad Professor who’s always putting out tunes, Gussie P and all those guys, they’re thinking… I mean Prof is smart because Prof has his own downloading thing going because that’s the only way you can control it, you can counteract people who just upload stuff. People just upload the tunes on their site! They can just get up and make a website and just sell people’s stuff on it. It’s disgusting. But now hopefully because I’ve got Jack Russell music, it’s a kind of a publishing company that kind of retains and tries to sort out things for us. They have realised that people at PRS have tried to put a hold on the whole downloading thing so that artists can get something out of it, if you’re a composer or a writer, and the whole streaming thing.

And just be glad that people want you to do shows. Imagine if you were one of these artists whose voice was not working anymore. Who had the big tunes back in the day but today they can’t sing them anymore. They’re the people who I really feel for.

The good thing is, once artists like ourselves are still around to represent an era of the music when the music was analogue, it was proper. Because when I go into a dance I’m not just singing my tunes, I’m singing Promised Land, I’m singing Dennis Brown, I’m singing some Jacob Miller to bring that vibe, you know? And I’m telling you, every weekend for the last two years I have a show. Whether it’s a sound system or a live band, for me that’s the only way that I can be able to still survive doing music. I was lucky enough to have the tune, the tune that I did with these guys Leftfield, it’s a tune that every six months I get a little money from the publishing. Because it was one of those songs that went global. But it’s not nice what’s happening out there. It’s rough, man. The amount of bootlegging thing that’s happening. So now I think Gussie and me are planning to put out some serious 7”s about the bootleg thing.

I did a track recently called Reggae Technology which was on the Reggae Ambassador album talking about the whole thing: the record shops are moving slow, the internet is taking over. It’s unbelievable how easy it is to gain access to the whole thing now. My kids showed me how to take a tune from YouTube, transfer it to MP3 and just have it playing. He said to me “Dad, it’s easy” and I said “It’s easy for you, but I find it hard to do something like that”. The amount of CDs… when I go to a record shop, like I go to France to my friends at Patate Records, I’m coming back with at least ten or fifteen CDs. I always find something, like an old Studio One and that’s the only way I can get it. That’s the way I want it, so I can play the whole CD, look at the sleeve, read the writing and things. Or the album, the vinyl – that’s how you enjoy music. I don’t know how some guys can go to a dance with a laptop and then he’s playing for two hours from a laptop. To me, I’m not sure man. I mean, whatever suits them, but it’s not the same as having a good sound system, watching a selector dropping the needle.

Some guys can go to a dance with a laptop but it’s not the same as having a good sound system, watching a selector dropping the needle

Some guys can go to a dance with a laptop but it’s not the same as having a good sound system, watching a selector dropping the needle

You can hear the difference. If you’re at a dance and someone turns it over to a laptop halfway through the sound changes.

Vinyl’s warmer. You literally hear on the laptop it’s much lighter, it’s kind of more pan-ish, the vibe and the feeling’s not there anymore.

I guess that’s why people have vinyl only nights. I don’t mind listening to digital tunes all night but it’s not nice when they change over from vinyl.

It’s mad, it’s mad, it’s crazy. My friends were saying that towards the end of the United weekend it was like a techno dance when everybody was playing from laptops because most of the sounds were packing up and stuff. So it was all just thin after you’d had Jah Shaka, Iration and all these mad sounds, then a guy comes in with his laptop it’s like “Wow, man. Time for me to head home” (laughs).

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z