Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Christopher Columbus in Jamaica

Christopher Columbus in Jamaica

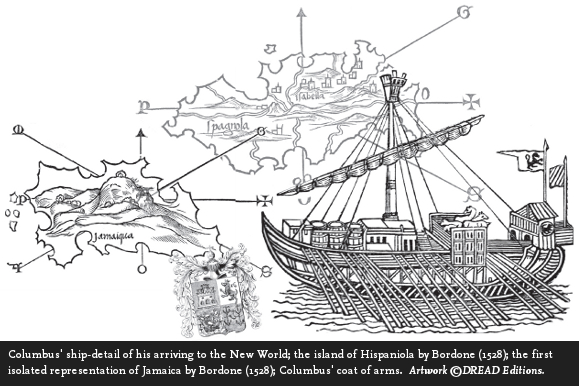

United Reggae offers an excerpt from Thibault Ehrengardt's book The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838.

Columbus discovered Jamaica in 1494, during his second voyage, as related by his biography, written by his second son, Ferdinand. The latter, aged 13, was from the 3rd voyage:

![]() On Saturday the 3rd of May, The Admiral resolved to sail over from Cuba to Jamaica, that he might not leave it behind, without knowing whether the report of such plenty of gold they had there, was in it, proved true, and the wind being fair, (...) he discovered it on Sunday. Upon Monday, he came to an anchor [St Ann’s Bay-editor's note] and found it the beautifullest (sic) of any he had yet seen in the Indies, and such multitudes of people in great and small canoes came aboard, that is was astonishing.

On Saturday the 3rd of May, The Admiral resolved to sail over from Cuba to Jamaica, that he might not leave it behind, without knowing whether the report of such plenty of gold they had there, was in it, proved true, and the wind being fair, (...) he discovered it on Sunday. Upon Monday, he came to an anchor [St Ann’s Bay-editor's note] and found it the beautifullest (sic) of any he had yet seen in the Indies, and such multitudes of people in great and small canoes came aboard, that is was astonishing.

The next day he ran along the coast to find out harbours, and the boats going to found the mouths of them, there came out so many canoes and armed men, to defend the country, that they were forced to return to the ship, not so much for fear, as to avoid falling to enmity with those people. But afterwards considering that if they showed signs of fear the Indians would go proud upon it, they returned together to the port, which the Admiral called Puerto Bueno, that is, Good Harbour [Discovery Bay-editor's note]. And because the Indians came to drive them off, those in boats gave them such a flight of arrows from their crossbows, that six or seven of them being wounded, they retired. The fight ending in this manner; there came an abundance of canoes from the neighbouring places in peaceable manner, to see and barter provisions, and several things they brought, and gave for the least trifle that was offered them. In this port, which is like a horseshoe, the Admiral’s ship was repaired, it being leaky, and that done, they set sail on Friday the 9th of May, keeping so close along the coast westward, that the Indians followed in their canoes to trade, and get something of ours. The wind being somewhat contrary, the Admiral could not make so much way as he wished, till on Tuesday the 14th of May, he resolved to stand over again for Cuba, to keep along its coast, designing not to return till he had sailed 5 or 600 leagues and were satisfied whether it was an island or a continent. That same day, as he was going off from Jamaica, a very young Indian came aboard, saying, he could come unto Spain, and after him came several of his kindred and other people in their canoes, earnestly entreating him to go back, but they could never alter his resolution; and therefore to avoid seeing his sisters cry and sob, he went where they could not come at him. The Admiral admiring his resolution gave order that he should be used with all civility.![]()

From May till July, the Admiral explored the Cuban coast, and then came back to Jamaica. Sailing along the coast from today's Montego Bay, he found a pleasant and fruitful country, with many harbours and villages. The Indians brought some provisions much better liked by the Christians, than what they found in the other islands. (Columbus) Every night, contrary winds forced the Admiral to cast his anchor into welcoming harbours, described as abounding in provisions, and so populous that he thought none excelled it, especially near a bay he called de las vacas [Cow Bay—editor's note]. There he came in touch with a Cacique, who had come to him halfnaked and wearing a head-lace with precious stones artfully put together, and locked on his forehead with a golden badge. The Indian asked Columbus to take him to Spain, but was denied. Eventually, after a full day spent at Portland Bight, Columbus resumed his tour of the island; upon reaching the eastern point, he headed to Hispaniola.

Columbus did not see Jamaica again until 1502, during his terrible 4th voyage. By then, he had been somewhat cast aside of the discoveries of the New World. When he asked Governor Ovando for permission to refit his damaged vessel, he was refused. He sailed away, desperately cruising the Caribbean islands. Suffering from the gout—a form of arthritis—, exhausted by all these years of adversity and sickness, he fought against the contrary winds of the region just like he had fought against those of fortune all his life. He describes his state of mind in a letter: “Hitherto, I have wept for others; but now, have pity upon me, heaven, and weep for me, O earth!” [Irving††† The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (New York, 1851)]. Things got from bad to worse. Because of their decayed hulls, the boats were falling apart; they banged into each other during a tempest—the first one lost her bow, the next one her stern and cables. When the Admiral miraculously reached Puerto Bueno in Jamaica, he had no choice: “The boats being unable to stand the sea any more,” says Herrera, “(the Spaniards) drew near the shore, within crossbow shot, fastened them, side by side, supporting them with scaffoldings (...). Finally, they were filled with water up to the deck; upon which, as well as at the sterns and bows, they built some apartments to accommodate the men.” Columbus was first and foremost concerned about providing his men with provisions. Diego Mendez de Segura, a prudent man of honour (Herrera), volunteered to walk from village to village in order to enter into arrangements with the Caciques. At the eastern point of the island, he made friends with the powerful Cacique Ameyro, bought a canoe from him, and then sailed back to the Admiral. “He returned in triumph to the harbor, where he was received with acclamations by his comrades, and with open arms by the admiral,” says Irving. This was yet a temporarily victory. Columbus was aware of it. He took Mendez aside, and told him: “Mendez my son (...) none of those whom I have here understand the great peril in which we are placed, except you and me (...). In this canoe which you have purchased, some one may pass over to Hispaniola, and procure a ship.” (Irving) Hispaniola was not that far from Jamaica, but the sea was rough, the currents unfriendly and the Spaniard's crafts derisory. It was a perilous expedition, not to say desperate. Columbus appointed a Genoa named Bartholomew Fiesco to go with Mendez—his orders were to come back to Jamaica upon reaching Hispaniola to keep the Admiral informed as soon as possible. Mendez, for his part, had to jump on the first caravel to Spain to carry letters to the Catholic Monarchs. The Castilians went to the eastern point of the island, and there waited for the best departure conditions with 6 other Castilians and 60 Indians. On July 7, 1503, Mendez and Fiesco embarked with their small provisions and all the water calabashes their frail skiffs could contain. “The Indians rowed restlessly, explains Herrera, and when tired, because of the heat or else, they jumped into the sea to refresh themselves, and then they returned inside their canoe.”

They lost sight of Jamaica the first evening, finding themselves between the sea and the sky the next day, already short of water and exhausted by their efforts under the boiling sun. Two days and one night later, the islet of Navasa, located on their way to Hispaniola, was not in sight yet. “They had already thrown an Indian into the sea, who had died out of thirst; others were lying unconscious at the bottom of the canoes, and those who remained, the more resistant, were quite melancholic, and waited for nothing but their time to come,” goes on Herrera. Having no strength left, they eventually reached Navasa the 4th day, where they recovered their strength before setting off again for Hispaniola. Notwithstanding Columbus' orders, Fiesco followed Mendez to Santo Domingo. Governor Ovando, upon learning about the misfortune of Columbus, did not rush to rescue him—he feared the reaction of the Admiral's many enemies, who lived in the colony. He reassured Mendez and Fiesco, and then sent one of Columbus’ enemies to make sure of the latter’s situation, forbidding him to rescue him.

Meanwhile in Jamaica, provisions grew few, and everybody wondered about Mendez and Fiesco, reckoning they had perished at sea. The Admiral's troops were restless, and he forbade them to leave the wrecked ships to trade with the Indians. His men were afraid never to leave this place; they were also angry at the Admiral, his brother Bartholomew and his son Fernand, and they expressed resentment more and more openly. One thing led to another and, on January 2, 1504, the dissidents led by 2 brothers, the Porras, came to the Admiral, weapon in hand. Columbus, then lying in his bed after a terrible attack of the gout, allowed them to leave the ships to avoid a blood bath. The Porras then took possession of the canoes bought from the Indians, and headed toward the eastern point of the islands with a majority of the crew. They intended to follow the footsteps of Mendez and Fiesco. But they refused to leave their belongings behind, and took them on board; as a result, the overloaded canoes let water in. The Indians were very good swimmers, and they knew how to make the best use of their canoes; they jumped into the sea when the water started to fill them, reversed them to empty them, and then jumped back into them. But the Castilians could not do the same—because of their belongings, first; and then, because they could not swim. As the water rose, they got scared, and threw away everything they could, including the Indians. The unfortunate were too far from the shore to swim back, so they swam besides the canoes until their forces gave up on them. Ten they asked for the permission to grab the canoes for a while, in order to rest. “But far from being that charitable,” relates Herrera, “(the Castilians) cut their hands off with their swords.” Eventually forced to turn back, convinced that Fiesco and Mendez coud not have succeeded where they twice failed, the Porras brothers and their men started to roam Jamaica, harassing the Arawak Indians.

Near Puerto Bueno, Columbus and his remaining men were worried, as the visits of the Indians—upon whom they depended for food—grew less frequent. Without them, they would not survive. According to the various historians, the Admiral always behaved correctly with the Natives—unlike his companions and successors. But the situation was critical. He then had quite a novelistic idea. He summoned all the Caciques to inform them that his powerful God, upset by their behaviour, had decided to darken the moon at night to cast them into everlasting darkness. His scientific knowledge had enabled him to foretell an eclipse—when it took place, the Indians threw themselves at the Admiral’s feet, begging for mercy. Columbus promised to do his best. The moon reappeared, and he never went short of provisions again.

The ship sent by Ovando appeared at last. Diego de Escobar, one of Columbus’ enemies, had a quick talk with the Admiral, and left him a small barrel of food before heading back to Hispaniola to report to Ovando. Columbus offered a portion of the barrel to the conjurers, but the Porras had made up their mind to bring it to a fight. The Admiral could not get up, so his brother took the lead of their small troop. The 2 parties met near Mayma, where the Spaniards later established their first settlement. The fight turned in favour of Columbus' troops. The Porras were taken prisoners, and all their men surrendered. The Admiral granted them his pardon to maintain peace until help arrived. At last rescued from the shore of Jamaica, Columbus reached Hispaniola where the conjurers were treated with a complacent indulgence. But he was too exhausted to take umbrage—he left the Americas on June 18, 1504, never to come back. Upon his arrival, he learnt about the death of his protector Isabella— the end of an era. Columbus died in Valladolid, Spain, on May 20, 1506, without fulfilling his divine mission, which, he believed, consisted in raising an army with the gold of the New World to liberate the Holy Sepulchre. Indeed, Columbus was a mystic man, tormented with visions and furies. (...)

This article is excerpt from the book 'The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838' by Thibault Ehrengardt (page 8 to 14).

This article is excerpt from the book 'The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838' by Thibault Ehrengardt (page 8 to 14).

Published in 2015 by Dread Editions.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z