Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

The Maroons, the Desultory Foes

The Maroons, the Desultory Foes

United Reggae offers another excerpt from Thibault Ehrengardt's book The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838.

The Maroons were runaway slaves, who regrouped in the hills to fight for freedom. The phenomenon was not typically Jamaican; Maroons could have been found almost all over the New World. But in Jamaica, they put up incredible resistance against the English for over 50 years. The Assembly passed 44 bills and spent £250,000 to eradicate them—but in vain. The Marrons went barefooted, and fought with derisory means, yet constantly defeated their enemies until the treaty of 1739. Unfortunately, the said treaty cast an everlasting shadow on their achievements. Actually, the descendants of slaves in Jamaica are today equally proud and ashamed of the Maroons.

The wild-Negroes

Before the English captured Jamaica in 1655, there were 1,500 African slaves living in the island. The Spaniards allowed them to live among themselves in remote camps. Masters at hunting wild cows, they provided the Whites with meat and skins—the latter were sold to other colonies—, and enjoyed relative freedom. But when Penn and Venables invaded Jamaica, they became soldiers. The Spanish Governor Ysassi taught them to harass the enemy. In the meantime, they kept on providing the Spaniards with meat. Ysassi did his best to make sure they remained loyal—when they shifted allegiance, the Spaniards definitively lost Jamaica. But some of the Spanish slaves sided the invaders like Juan de bolas. Others took advantage of the chaotic situation to stay on their own; they started to roam the island in small groups, and, knowing no friends, attacked every one. They settled on the foothills of the Blue Moutains and eventually became the Maroons. The name derives from the Spanish word cimarron—which translates to mean untamed. But at first, they were simply called the wild-Negroes. They planted corn and cocoa, and plundered the English settlements to improve their condition. Their camps became a refuge to runaway slaves, and a perpetual threat to the colonists. In the 18th century, the Whites lived in fear of an uprising. Probably because of the impressive amount of slaves on the island, and of the terrible tortures they inflicted on the Whites when they fell in their revengeful hands—also, as Carey Robinson suggests*, is a result of a heavy feeling of guilt.

Before the English captured Jamaica in 1655, there were 1,500 African slaves living in the island. The Spaniards allowed them to live among themselves in remote camps. Masters at hunting wild cows, they provided the Whites with meat and skins—the latter were sold to other colonies—, and enjoyed relative freedom. But when Penn and Venables invaded Jamaica, they became soldiers. The Spanish Governor Ysassi taught them to harass the enemy. In the meantime, they kept on providing the Spaniards with meat. Ysassi did his best to make sure they remained loyal—when they shifted allegiance, the Spaniards definitively lost Jamaica. But some of the Spanish slaves sided the invaders like Juan de bolas. Others took advantage of the chaotic situation to stay on their own; they started to roam the island in small groups, and, knowing no friends, attacked every one. They settled on the foothills of the Blue Moutains and eventually became the Maroons. The name derives from the Spanish word cimarron—which translates to mean untamed. But at first, they were simply called the wild-Negroes. They planted corn and cocoa, and plundered the English settlements to improve their condition. Their camps became a refuge to runaway slaves, and a perpetual threat to the colonists. In the 18th century, the Whites lived in fear of an uprising. Probably because of the impressive amount of slaves on the island, and of the terrible tortures they inflicted on the Whites when they fell in their revengeful hands—also, as Carey Robinson suggests*, is a result of a heavy feeling of guilt.

D’Oyley set up an expedition to eradicate the wild-Negroes, killing most of them. Those who surrendered had to prove their loyalty by tracking down their former friends into their most inaccessible hideouts. They killed many, offering the English a victory beyond their capacities. Leslie confirms: “In such a sultry climate, the fatigue of climbing the precipices, and the very load of their arms was almost intolerable to an European constitution.” D’Oyley was about to exterminate the last groups of them, but he did not. Was it because the project was not that easy? Or because 2 rebellious Colonels in his own army—who were executed shortly afterwards—, defied his authority at the time? The expedition was aborted and a few dozens of wild-Negroes were left alive. Within the next few years, they became deadly predators, shifting from the status of wild-Negroes to the one of Maroons. They became the plague and the nightmare of White Jamaica. Breastworks and forts were built in the plains. The expenditure was colossal, and the danger continuous. Furthermore, runaway slaves joined their ranks daily. “Soon, the Africans left the plantations by the hundreds,” writes Raynal, “after they had slaughtered their masters and plundered their houses that they set afire. In vain were some active partisans used against them, who were promised £900 for each killed—that is for a severed head. This was useless, and the desertion became more general.”

The Coromantyns

Slavery is an ancestral custom, but the triangular trade was exceptional in its proportions. More than 10 million people were deported over 400 years. Though such a figure might suggest a form of docility, the history of the New World is interspersed with slaves’ revolts. History was written by the strong, who have not recorded all the acts of bravery of the weak—first to avoid the setting of bad examples, and then to justify themselves. But the slaves rebelled so many times in Jamaica that it would have been impossible to conceal it. Yet, the colonists had an explanation. Jamaica, they said, was the slave drivers' first stop on their way to the continent, where they got rid of the most turbulent slaves. Among those slaves, bought in Senegal, or at Fort James on the Guinea River, were the Coromantyns. They were admired for their robustness and their determination, but they were also feared. Cudjoe, the historical leader of the Maroons, was a Coromantyn; so was Quao, or Tacky, the emblematic rebel of 1760 (see chapter 10). The historians praise their physical capacities, even those who disliked them like R.C. Dallas† or Bryan Edwards. The first says: “Vigour appeared upon their muscles, and their motions displayed agility. Their eyes were quick, wild, and fiery (...). They possessed most, if not all, of the senses in a superior degree.” The latter goes on: “Their mode of living and daily pursuits undoubtedly strengthened the frame, and served to exalt them to great bodily perfection.(...) The muscles (...) are very prominent, and strongly marked. Their sight withal is wonderfully acute, and their hearing remarkably quick.” They were responsible for most of the spontaneous and disordered revolts in the island. Although quickly suppressed, these uprisings remained scary, since they were unpredictable. Leslie tells about a specific one that took place on the estate of a planter who was famous for his riches and justly valuable for his generous and hospitable disposition. Our "rich and generous" man took in a slave whom he found dying on the roadside. He became his property. But punishing him one day for some fault, he made a deadly foe of him. The ungrateful creature soon assaulted his master’s house with a bloodthirsty party, finding his benefactor lying in bed. The wild-Negroes tortured him to death with the rest of his family. “All the barbarities that could either be invented by cruelty, or committed by rage and fury, were practised upon these unhappy men,” says Leslie. “Some of them were indeed dispatch’d in a minute. This was not owing to the mercy of the Negroes, but to the haste they were in. Others had a harder fate; for this resolute set of murderers took as much pleasure in torturing them, as well-disposed souls takes in acts of kindness and beneficence.” About the same story, Edward Long gives more details, calling the victim Mr B—, and stating: “Being overpowered by numbers, and disabled by wounds, he fell at length a victim to their cruelty; they cut off his head, sawed his skull asunder, and made use of it as a punch-bowl.” The rebels then retreated into the hills of Lecuvard, where more runaway slaves regularly joined them—they became the terror of the North Coast.

The First Maroon War

Following their many victories, the wild-Negroes grew confident and decided to take the island in 1690. This was the first Maroon war. In a concerted movement, several rebellious groups attacked various plantations all through the island. Governor Williams, second Count of Inchiquin, had just arrived in Jamaica. He sent his troops against the Maroons; but the latter refused to fight in the open, and hid in inexpungible caves instead, defeating their enemies in short but repeated skirmishes. The English troops came back, exhausted and disheartened. As a result, the slaves started to get nervous on the plantations. At Suttons Estate, in the parish of Clarendon, 400 of them assaulted their master’s house. According to Leslie, they cut the throat of Mr Sutton and his family, but Long only tells about the murder of a white Overseer. They sacked the artillery, and then headed to the nearest plantation. From the neighbouring parishes, the English sent 50 men, horse and foot. Ill organised, giving way to panic, the rebels went back to Suttons Estate, from which they were dislodged the following day. “The rebels withdrew to the cane pieces,” writes Long, “and set fire to them, in order to cover their retreat; but a detachment of the militia having fetched a little compass, found means to assault them on flank, while the rest advanced upon them in front; unable to withstand this double fire, the rebels immediately fled, but were so briskly pursued, that many were killed, and two hundred of them threw down their arms, and begged for mercy.” The English confessed 16 dead—which is quite unlikely. Once identified, the leaders were hanged, but a handful of rebels got away and vanished in the hills of Clarendon. Among them was a short and stout Coromantyn, who went by the African name of Cudjoe. The English relations as well as the engraving joined to Dallas’ book, represent Cudjoe as a hunchback—but this is doubtful. He might have been stout, but the way in which he led his troops in the steepest relief of the island proved that he suffered from no major physical disability.

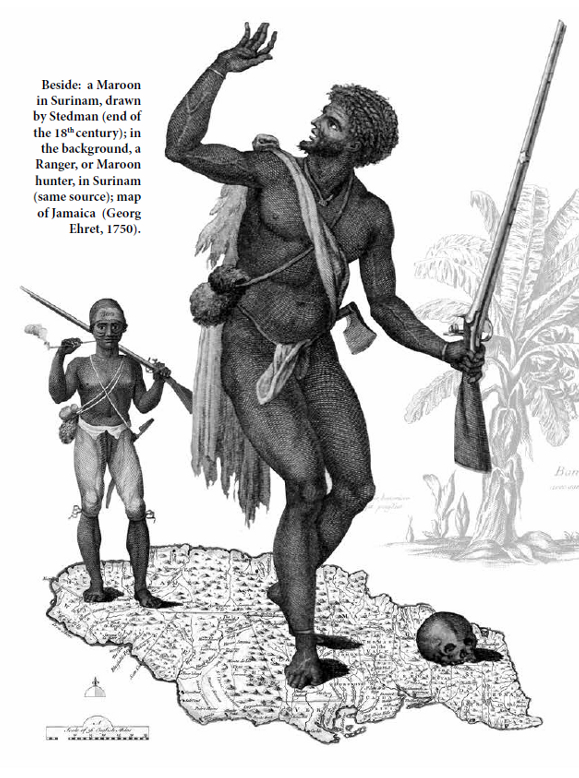

As soon as 1656, Sedgwick was worried over these wandering Negroes, who refused to negotiate. Foretelling that they might become thorns in the side of the colony, he confesses his helplessness in a missive sent to Thurloe in England: “Having no moral sense (...) and not understanding what the laws and customs of civil nations mean, we know not how to capitulate or treat with any of them (...) They must either be destroyed, or brought in upon come terms or other; or else they will prove a great discouragement to the settling of people.” The colonists called upon the Mosquito Indians and their hunting dogs to dislodge them—but in vain. Soon, it was impossible to circulate but on the perimeter of the island. The rest of the colony belonged de facto to these dreaded wild-Negroes, who, by their barbarities and outrage, intimidated the Whites from venturing to any considerable distance from the sea-coast. (Long) In 1660, Captain Ballard disbanded the troop of the Vermaholis Negroes. But this was a small victory. The helpless English promised to pardon every repentant wild-Negro, and to allot him a plot of land. None took the offer. Worse, Juan de Bolas, the former Spanish slave who had joined the English after the invasion of 1655, was ambushed and killed by a group of Maroons. Little has been written about these black troops that fought the Maroons. In Surinam (Dutch Guyana), they were called Rangers. At the end of the 18th century, John Stedman, a young English officer infatuated with the ideas of the Lumières, wonders about their motivations. “What would men not do to be emancipated from so deplorable a state of subjection? (...) Having thus once engaged in this service, it is evident that they must be considered by the other party as apostates and traitors of the blackest dye; they must be convinced that defeat must not only expose them to death, but to the severest tortures; they were therefore fighting for something more than liberty and life: (...) miscarriage was to plunge them in the severest misery.” Stedman reports a discussion he overheard between some Maroons and some Rangers during an expedition: “The former reproaching the rangers as poltroons and traitors to their countrymen, and challenging them next day to single combat (...). The rangers d—n’d the rebels for a parcel of pitiful skulking rascals, whom the would fight one to two in the open field if they dared but shew (sic) their ugly faces; swearing they had only deserted their masters because they were too lazy to work.” Stedman immortalized one of these Rangers with a wonderful drawing; he did the same with a Maroon—it is often used to illustrate the story of the Jamaican Maroons, as contemporary engravings are badly missed.

The English had to give up a vast part of Jamaica, but they never stopped trying to find a solution. Three expeditions were set up in 1730. The first one got lost in the morasses, where many soldiers drowned. The second one, though reinforced by a regiment from Gibraltar, underwent very important losses which forced it to turn back. The soldiers from the last one, after many days of a tedious walk and several inefficient skirmishes, realized that they were going nowhere fast. The Maroons of Winward and those of Clarendon had established a permanent and fleeting front as the threat was perpetual and unpredictable. The way the Maroons lived in their camps proved their determination. Always on the alert, deprived of commodity, and surviving through plundering and murders, they not only feared the English but also the traitors who would sell them out for a handful of pounds. This was a tough life. Their knowledge of the field and their speed of reaction allowed them to resist an ill-equipped and ill-adapted enemy. The abengs, those emptied cow horns used as trumpets by the sentinels, sounded the arrival of the English from hill to hill. They gave a powerful and modulating sound—the Maroons used it to coordinate their attacks or retreats. The only arms they had were taken to the enemies. They only fired when assured to hit their target, and thus became diabolically good shooters. They plundered isolated plantations for gunpowder. At first, the slaves supported them by letting them know of their masters' plans. They also used to give them a portion of their provisions. Some Maroons joined the crowd in Kingston, on market days, to buy a few bullets under the English’s nose. On the battlefield, they proved to have been astonishing warriors. “No sooner is their piece discharged, than they throw themselves into a thousand antic gestures, and tumble over and over, so as to elude the shot, as well as to deceive the aim of the adversaries, which their nimble and almost instantaneous change of position renders extremely uncertain,” says Edward Long. Then he adds with contempt: “In short, throughout their whole manoeuvres, they skip about like so many monkies (sic).”

In 1730, the colony set up a militia dedicated to fight the Maroons exclusively. The Captain received £4 a month, excluding premiums. Indeed, he got £10 for each Maroon captured alive—the prisoners were then transported to another island—, and £40 for each severed head; the last option obviously offering more profits and less complications.

The Destruction of Nanny Town

Though indomitable, the Maroons remained in a precarious situation. Their war effort required many sacrifices. And they experienced a few backlashes, too, including the destruction of Nanny Town, in 1734. The name of this legendary Maroons’ hideout in the Blue Mountains, derived from Nanny, the elusive female warrior—later raised to the rank of National Hero, she appears on the current $500 (...)

This article is excerpt from the book 'The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838' by Thibault Ehrengardt (page 8 to 14).

This article is excerpt from the book 'The History of Jamaica from 1494 to 1838' by Thibault Ehrengardt (page 8 to 14).

Published in 2015 by Dread Editions.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z