Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

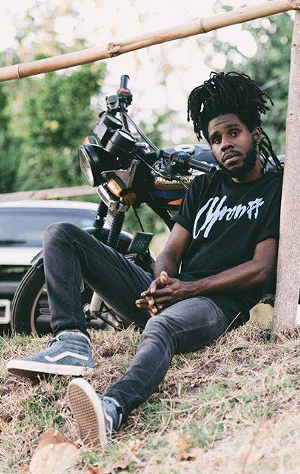

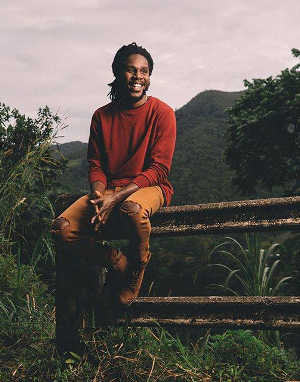

Interview: Chronixx (2017)

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Chronixx (2017)

Interview: Chronixx (2017)

"I don’t go out searching for topics"

Sampler

Interviewing Chronixx is always a very intense experience. Here the enigmatic singer-songwriter shares some thoughts and memories of family life, his early career, his new album Chronology, and a range of other topics, ranging from spiritual matters to social media and back again.

I would like to start back at the beginning and hear a bit about your formative years.

I was born and raised in Spanish Town, Jamaica, and for me, growing up was a very fun experience. As a child, I had less expectations; life was more about learning. Then you was a student in every single way: you had to listen to your parents, your teachers, the older people around you, and even to your other siblings. So it was a great thing, and that’s how my love for music was developed, from me having to learn songs at church, or learn songs at home, and it’s through learning that I discovered things that I liked: at school, we had to do crafts and drawing, and that’s how I discovered that I love art. So it was through being a little child in his innocence, running up and down and knowing that to come over this life experience and to truly get a hang of it, I would have to learn. And I love learning.

Were you raised by your parents in one household?

Yeah, my parents and my grandmother, and I had two sisters, four brothers and one cousin.

Where are you in the hierarchy?

Well, I’m kind of like the middle one. My two sisters are older, two of my brothers are older than me, and then I have two younger brothers.

What kind of work were your parents doing? I know your father was a performing artist, but was he doing other work, and was your mother working too?

Well, my mother now, she is really a tradeswoman, she’s really a creative person who used to do dressmaking at one point, and she used to do hairdressing; she kind of make the most of all of her abilities, but the main thing for her was dressmaking, and she had other little businesses that she took care of, like she would have a shop in the town where they sell clothes and all of these things. She was a very industrious kind of person, she had a lot of natural talents and abilities and she’s a very driven person, so she just did all of those things that she could do, and then my father did only music, and sound system business.

And you’re named after him? You’re Jamar McNaughton Junior, and he’s Jamar McNaughton Senior?

Well, that’s one of the many things that Google have twisted people about, you know?

My father’s name is Selwyn George McNaughton and my name is Jamar McNaughton, so there’s no Junior and no Senior. None of my father’s children were named off him like that; my father’s name is Chronicle, so, you know, people would just call us Chronixx.

What district of Spanish Town were you living in, or did you move around?

I was born in De La Vega City and we lived there for a very short time in my infancy, and then we moved to Ensome City, but a lot of our family still lived in De La Vega City, so it was back and forth; our church that my mother went to is there, and my father’s friends are there, my family are there, so we would go there basically every day, and especially when I started to do music, the studio was there. So I went there basically every day for the studio.

Which church did your mother attend?

She attended the Lighthouse Assembly, in Jamaica them just call it Church of God. It was a Sunday church, and in Jamaica we don’t really care about [denominations], unless you are a Catholic or some form of Methodist or something, but otherwise, it’s just church.

A lot of spiritual people tend to downplay the spiritual importance of music

A lot of spiritual people tend to downplay the spiritual importance of music

But you’re saying that music was an important part of that church experience, and that was your earliest experience of music?

Yeah, I mean, Jamaican church life is 90% music. Apart from everything else, music is the main attraction, always. No matter what you see out there that has music accompany it, you just try for a second to take the music out and see what you are left with: nothing. And a lot of spiritual people tend to downplay the spiritual importance of music. Music is a spiritual thing; a lot people are not conscious of it, but music is the most spiritual thing, because it is the one thing that you can’t see, you can’t touch it, but it can touch you, it can see you and it can feel you, and it can follow you around in your head, but you can’t follow it, you know? Because you can’t see it. So music is the only thing. Like when we produce music, nobody can really see it; like when I sing, nobody can see what I’m singing, they only hear it and feel it. It’s invisible, so it’s spirit. A lot of people take that for granted, that music is spirit, cause remember, humans can manipulate spirit, and that’s why you have people that will just sing any kind of music, because they are just manipulating the spirit, some people for money…even in church, you will find that the music is just a thing to attract people.

Is it true that you wrote your first song when you were five years old?

Yeah, I made my first song when I was five and I made it up in my head. Cause I was five, I couldn’t write; probably I could write my name, but I definitely couldn’t write a song, but I made up a little song, you know? And it’s funny, because a lot of youths in Jamaica have their likkle songs that they make up; by the time you are three you start to make up music.

Yeah, I made my first song when I was five and I made it up in my head. Cause I was five, I couldn’t write; probably I could write my name, but I definitely couldn’t write a song, but I made up a little song, you know? And it’s funny, because a lot of youths in Jamaica have their likkle songs that they make up; by the time you are three you start to make up music.

What was the song? Do you remember it?

Yeah, I remember it, but I don’t sing it a lot. Certain songs I don’t even sing, I only sing them in private. Like when I’m alone, or whatever, I just sing them, because it helps to remind you, it helps you to remember stuff. So there are certain songs that hold a lot of memory with them for me; even if I’m to hear certain recordings, it would bring back a whole chapter of my life. These are songs that I remember and pieces of them, remnants of them, are in the songs that we now know today.

So you remember it from that time, and you work in a line or two now?

Yeah, man. Sometimes not even on purpose, but these are songs that have been a part of my meditation from I was a child, so these are like the seeds were everything grow from. All my song-writing principles, everything that I practice in music comes from these things.

These are songs that have been a part of my meditation from I was a child

These are songs that have been a part of my meditation from I was a child

I read about one called “Rice Grains.”

That’s the one.

What was it about?

It was about life in the ghetto, about curfew and police presence in the community and military presence in the community, and people [who] don’t have much to eat; it was about that kind of life and it’s funny that when I was five years old, that’s something that I should sing about, but the song say, “A soldier want come bust through we gate, but nobody no want fi pick up the rice grains.” So these were the words in my meditation as a little youth.

My limited memory of Spanish Town is that, from the late 1990s going into the early years of the new millennium, it began to be increasingly associated with a particular kind of violence, linked to political affiliation, and other types of violence, and that comes through in the message of that early song of yours. But at the same time, it sounds like you have a lot of positive memories of growing up there, and even the song “Spanish Town Rockin” is a very positive portrayal of Spanish Town.

Yeah, look at it this way: if you is not really a person who is closely linked to certain activities…because we’re attracting things into our lives by associating ourselves with things, in a mental way and in a spiritual way and in a physical way, you know? If you were living in Vietnam during the war, you would have been affected by it. And it’s just your positioning and the people you know, what you choose to associate yourself with. I mean, there’s a lot of positive, outside of people being drawn into certain things, or being affected by it; everything else is just positivity, you know?

My first song, when I was five years old, was about life in the ghetto, about curfew and police presence in the community

My first song, when I was five years old, was about life in the ghetto, about curfew and police presence in the community

Is it true that your father gave you the mic when you were six years old? Were you already on stage shows then?

No, we used to go into the studio, and we used to have our own little talent shows at home, where you would make yourself sing whatever you wanted to sing. And then we now as children, we would always like to make up our own songs, or create our own versions of things, but we would start performing for ourselves and for [our father] and for family, til eventually we started to sing in church, til eventually we started to sing at weddings. So different stages, you know?

When did things become a little more concrete? When did you start to sing more professionally? And what about building your own rhythms and so on?

As soon as I was thirteen, them age there…but I started recording when I was like eleven. The first song I recorded was a tune called “Call On Jesus.” It was a gospel song that I recorded at my friend’s studio; it was me, my brother and my two sisters. We had a group called Hearts of Worship, it was a group that mainly performed at our church and then, together we would do harmonies for various people.

What studio did you go to, to do that song?

It was a studio in a place called…um…I don’t even remember what that place is called. It’s in the Spanish Town area.

Who used to run it?

A brethren named John. And then one of our cousins who was a deejay, his name is Lieutenant Brooksie, he brought us to John’s studio and we recorded, and these times we were recording gospel music on roots rock reggae rhythms, like some old Studio One rhythms, some Sly and Robbie vibes.

Was any of that released?

No. People might even have versions of them on CD and cassette, which would be very precious; I think even I have a few versions of it somewhere. So we went and we started recording music, and that was our first song that we did together, but my first recording was really with Jermaine Edwards at the Lighthouse Chorale; at the church that we used to go to, we was a part of the choir, and then Jermaine Edwards, who was one of the main musicians at the church, and he’s now a very popular Jamaican gospel artist, he started to record music and brought us to the studio with him, and we start to do sessions at Tuff Gong actually, and that’s how I met the engineers at Tuff Gong and I work with them still, up til today.

Did you continue doing gospel music at Tuff Gong?

No, that was the only times I went there, like four or five times, or probably even less; that was the only time that I went there to record gospel music, and I think one more time with Lester Lewis, who is also another popular Jamaican gospel artist. As I said, we used to record harmonies and background music for a lot of these people.

So, some of those were released?

I’m not even sure. I was a child and I just wanted to sing and record music.

Were you paid?

No. I was like, eleven, twelve. I didn’t really care about money that much, and for my parents, it was God that we were doing it for.

You did it after school?

Yeah, definitely, you’d do it after school and on weekends.

The music that I wanted to do was spiritual music and not religious music

The music that I wanted to do was spiritual music and not religious music

What happened from there?

Basically, my brothers and sisters just stopped recording, because they were older than me and as you get older, you can’t just continue singing for free. So when there was not enough paid things to do, people just went on with their lives, and I was still young and in school, so I continued to go to the studio and I wanted to now record on my own, just do music solo, and the music that I wanted to do was spiritual music and not religious music, and people wasn’t really interested in that kind of thing. So I had to learn how to produce and record myself, and that meant more time in the studio.

When you say spiritual music and not religious music, were you gravitating towards a Rastafari consciousness? What do you mean by that, exactly?

You can separate that part from Rastafari; we could record songs without even mentioning the word Rastafari, and still include all the spirituality that it entails. Rastafari for me is a more personal spiritual concept which, what’s personal in terms of Rastafari is how it spirituality manifest itself in my life, and how spirit manifests itself to me, but for other people it might be through the principles of yoga and various Oriental spiritual practices, Indus Valley spiritual practices, you know? For a lot of people, it’s more Southern American, Pacific spirituality. I mean, me’s a more Afrocentric kind of vibes where, that’s how it resonates in me as a youth who is born in Jamaica as an African, born in Jamaica. You know? The spirituality manifests itself to you in the ways that it is…because spirituality is a practical thing, it’s not just something that you read about and whatever. So I wanted to do music that could facilitate my spirituality and introduce more people to what spirit is, and what spirituality is. But people wasn’t really interested in that kind of music, you know? So I had to produce it myself. I had to learn, now, I had to go and learn how to produce and use all the different software and hardware and the basics of production. I did that just about everywhere I could, so I had to go from studio to studio, different studios, and I also spent a lot of time at home, just watching Youtube and watching videos, reading books and practising the different softwares, start developing a work flow for myself, which left me with a very unique work flow, like, the way I how I produce ended up being very unique, because I didn’t really learn in a school or in any formal way.

Rastafari for me is an Afrocentric kind of vibes, as a youth who is born in Jamaica as an African

Rastafari for me is an Afrocentric kind of vibes, as a youth who is born in Jamaica as an African

Before you were making your own music more concertedly and more actively, did you do some recording for Main Street, or you were involved with that studio and Danny Browne in some way?

Well, it’s good that you have done really good research because you’re bringing up some things that I would otherwise leave out of this interview. So basically now, while recording gospel music still, Jermaine Edwards, he started to become more and more popular, he was invited to the studio, and this was a very good thing that Jermaine did at the time, because he didn’t have to do it…basically, Danny Browne had a compilation that he released, I think maybe every year, I don’t remember how often, but he had a compilation Various Artists album that he produced where there was now a thing called dancehall gospel music, so you have a lot of artists like Papa San, Stitchie, Carlene Davis doing more reggae music, and Prodigal Son; Jermaine Edwards was kind of new on that scene, he was doing that cultural Jamaican gospel music, which, his version of it was more of a fusion of American black gospel music and Jamaican music. So he was now invited to be a part of that album and he brought me, cause we had a song that we was making together, when I was like, twelve, you know? And I was excited because this was Danny Browne and I know Danny Browne from my father, who was a person in the dancehall, so from you know Goofy and Red Rat, all of them tune there, General Degree, all of them Main Street music, it was a big deal. And as a youth who spent a lot of time around gospel music, at the time he was one of the biggest producers, so it was a big deal. Anyways, the session went up in total shambles: I went there and he felt like I wasn’t delivering good enough and I trusted him. So when said that the delivery wasn’t good enough, I really hung onto that and went home and worked on my delivery, and I ended up didn’t recording that day, well, I did record but the song wasn’t finished and it wasn’t released. So it wouldn’t work with Danny Browne again until I did “Thanks And Praise,” that was the next time I worked with Danny Browne, that was 2013, 2014.

So, after the gospel phase, you were starting to make your own music. The first thing I became aware of, it’s not until 2011, but presumably you were already doing things from 2-3 years earlier than that on your own?

For me, music is just a endless journey, it’s just where you started to become more recognised for what you was doing, but other than that, I was always doing music, so I was always producing and doing everything. So when I started producing, I was producing with Lutan Fyah, writing with Lutan Fyah, I was producing with other producers. I remember doing a rhythm that they ended up recording with Popcaan and Vybz Kartel on it, the rhythm was called “Freezer Rhythm”; Popcaan’s song was called “Real Bad Man,” and Vybz Kartel’s song was called “Watch Dem.” I also produced a tune that Konshens did, I don’t remember what that song was called, and I also produced a rhythm that Munga Honourable recorded on, that was called “Where We Have.”

For me, music is just a endless journey, it’s just where you started to become more recognised for what you was doing, but other than that, I was always doing music, so I was always producing and doing everything. So when I started producing, I was producing with Lutan Fyah, writing with Lutan Fyah, I was producing with other producers. I remember doing a rhythm that they ended up recording with Popcaan and Vybz Kartel on it, the rhythm was called “Freezer Rhythm”; Popcaan’s song was called “Real Bad Man,” and Vybz Kartel’s song was called “Watch Dem.” I also produced a tune that Konshens did, I don’t remember what that song was called, and I also produced a rhythm that Munga Honourable recorded on, that was called “Where We Have.”

The “Freezer Rhythm,” the songs were released on 45s on the Icebox label?

Yeah, Ice Box Recordings, it was somebody I was working with. He’s from De La Vega City, Freezer.

Is he still making music?

Yeah!

Is Lutan Fyah somebody you knew from Spanish Town, or just somebody you bucked up on in the studio?

I knew him from Spanish Town, he’s my father’s brethren. Because there’s a Rastafari community in Jamaica, and most of the artists in Spanish Town were positive artists, you know? That’s what people don’t realize, that almost every artist I know in Spanish Town is cultural artists, because it’s a deeply cultural place and our connection to music is a cultural thing. We were already surrounded by so much violence; that’s why I sing about it, we were surrounded by so many guns, but even the people who persons would consider a bad man, he only listen to Sizzla. It wasn’t until later down when people started gravitating towards the whole Gaza and Gully, Movado kind of vibes, but conscious music, spiritual music and cultural music was the mainstream thing in Spanish Town, and when the studio was built in De La Vega City, that was the music that was produced there. We had artists like Turbulence recording there, Fantan Mojah, it was that era of musicians that was most influential to us, Lutan Fyah, I-Wayne, Sizzla Kalonji, Jah Cure, it was mainly them kind of artists that was most influential to us as youths, with Lutan Fyah being the main one out of the pack, because he was from there and he was on the rise in Jamaica, and we felt very good about that, that somebody from our community was being recognised for the good music that they was making. Even in the heights of the whole Gaza and Gully whatever, we were still there making positive music, reggae music.

Almost every artist I know in Spanish Town is cultural artists

Almost every artist I know in Spanish Town is cultural artists

There must be some kind of turning point, when you start making your own music and begin to make an impact. And in 2011, we get the first actual mixtape release…

Before you go to 2011, I met Teflon late 2009, 2010, while I was producing at a studio called Kings of Kings; because of certain violence, the studio in De La Vega City basically got closed down, and they relocated to Kings of Kings studio in Half Way Tree.

You mean, with Scatta Burrell and those people?

No, Scatta wasn’t using the studio anymore, Clive Hunt was using the studio. I had been working closely with and alongside, understudied Clive Hunt from in De La Vega City; he used to produce at the studio every Thursday. And then, when the studio moved and they brought all the operations to Kings of Kings studio, that’s where I was, I used to spend all the nights there.

Was Iley Dread still part of that?

No. Basically, Clive Hunt use the studio during the daytime now, and when he left, we just had the studio to do whatever, so in the nights it was me, Goldie, and Clive Hunt’s son, Maurice, it was just us at the studio every night, so we just do whatever we want to do. So that was the first time I really had a studio to experiment in, like a real studio! So anyways I met Teflon there and when I started to produce with Teflon, the producer, Zinc Fence Records; he came to the studio and he was trying to get out there as a producer, so basically we were doing the same thing, trying to get out there as producers, and we say, “Yo, let’s link up and make some music together.” So I started going to his house where he had a likkle set up, and we produce every single day, and at that time he was working at Cable and Wireless, so he would go to work during the days and then in the evenings now, we just produce. So I was just there producing and producing, and writing music until we started to…well, our main thing was to work with other artists, I would write the songs and we would try to get other artists to record the songs, anybody who we thought was talented.

Were any of those things released with other artists?

No, it didn’t work out very well, because a lot of these artists was very unreachable for us, or some of them was unaffordable, so I started singing the songs myself and that’s how it started.

Is this some of the material that ended up on the Hooked On Chronixx release?

Yeah mon, all of them were songs from that time, when me and Teflon was producing.

When I think about that material, if I contrast something like “Start A Fyah” with “Behind A Curtain,” for instance, “Behind A Curtain” is so much more grounded in dancehall; there’s kind of a dancehall undercurrent, but then, you’re much more in a roots reggae mode on some of the other material.

Yeah, because, I remember I started out on roots reggae, that’s the music I really started to practice first; when I started making my own music that I wanted to make, that was the first music that I wrote and performed, cultural music. But then, when I started producing, dancehall was the music that I produced, you know? So as a producer, I would say I am more of an experimental dancehall producer, and as a writer I would write more cultural, you know? So the music that people get from me, even today, is a reflection of that. Like, for instance, one of my most recent songs, “Likes,” is a song that I produced, and its dancehall. Whatever I put my hands on will be very rhythmic, a dancehall kind of vibes, and yeah, I also produce a lot of cultural music, reggae, roots, dub, ska, that kind of vibe. I produce just about everything, but dancehall comes more naturally for me as a producer.

As a producer, I am more of an experimental dancehall producer, and as a writer I would write more cultural

As a producer, I am more of an experimental dancehall producer, and as a writer I would write more cultural

So when you were growing up, is it that you were listening to more dancehall? Why would you say it is that, as a producer, it’s easier for you?

I don’t know. I couldn’t tell you the fine details as to how or why, it’s just, whenever I go to build a rhythm and the drum pattern, it’s dancehall. And from there, no matter what you put over that drum, it’s just dancehall, and actually, when I go into the studio with musicians now, it’s a different story. Like when I go to produce with musicians, you would get more soulful roots reggae, more traditional Jamaican sounds.

But at this point in the tale, there was no Zincfence Redemption Band as yet?

No.

You were just working with musicians and building rhythms on your own?

Yeah, along with Teflon and also the twins from Vineyard Town, Jahnai and Ijah, Jah Ova Evil, that was the main team, the core people who I work with during that time, the whole Start A Fyah time. I would have met Protoje already and Kabaka and all of these people, and actually Kabaka was the one who brought me “Start A Fyah” rhythm to record on.

It came from Jungle Josh Records?

Yeah, a brother called Joshua from California, he produced that rhythm and I recorded it, and actually the version that is out, I actually mixed it as well, and I was very bad at mixing at the time.

Kabaka and the Jah Ova Evil crew, they were just people that you met along the way?

Yeah, because Romaine [Teflon] is originally from Vineyard Town, so that’s how I met the rest of the Vineyard Town people, and then I met Kabaka through Protoje. And I just kind of met up with Protoje because me and him and Romaine wanted to produce a song with him, so we went to his house, this was when he already finished his first album, Seven Year Itch, and I went to his house to play the ideas for the songs, and I ended up playing him some songs that I had written and recorded, but I didn’t really plan to release them or anything, that was just like, the demos, meant for the artists. Anyways, he liked it and from there we started linking up and writing together.

On the Start A Fyah mixtape, you have Infinite on one track too, “Capitalists.”

Yeah, Infinite is another youth from Vineyard Town who I work very close with, and one of the people who brought me closer to playing instruments and being a more versatile artist, not just in an imaginative way, but in a practical way, like encourage me to play different instruments and do different things in music. Infinite, he raps, he plays guitar, he sings, wicked deejay too, and him produce.

This was like your first album, even though it did not come as a physical album, and already, some of the tracks, like with “Warrior” and “Wall Street,” even though the topics are about things that people can relate to wherever they are…

And topics that people weren’t singing about at the time. So as I was saying, I wanted to be a more spiritual artist in terms of, I wanted to do music that come from my spirit, and come from my spirituality, and I wanted to do music that linked directly with the way how I live, and the way I think, the way I feel. So, that’s where, for me, I don’t go out searching for topics. Like, whenever I make music, I just sing about the things that are most immediate in my life, things that I’m inspired by, things that I see and things that I feel around me and in my environment. So that’s where those songs and the inspiration for those songs come from.

For me, there’s continuity in your work in that the songs are deeply personal, and I would say, on the new album Chronology, that’s especially evident. So once you do the Walshy Fire configuration of Start A Fyah, you start to get some serious airplay and the world becomes a bit more aware of you, and then you have some songs come out like “Smile Jamaica,” which made quite an impact, and then “Here Comes Trouble” which made even more of an impact. And going through the “Dread And Terrible” and “Roots And Chalice” phases then brings us up to the new album. What can you tell me about that phase of evolution, and what started to happen then?

Well, a lot of those songs came about when I started working with other producers, you know. I was now given the opportunity to work with more musicians from all over the world. So, it kind of affected the way how I would write and perform, and a lot of these songs weren’t even written, I just went into the studio and said whatever was on my mind on that day, you know? Like “Smile Jamaica” for instance is a total magic, how that song was made, because that song was made before I met the producers or even knew who produced the song.

You already had the lyrics?

I already had the lyrics and already knew the rhythm, because I was at Kings of Kings studio a very long time before I recorded the song, like maybe two years, and found the rhythm on the desktop, and I didn’t realize until later that it was Lutan Fyah who was recorded on the rhythm. And I went home and wrote the song to the rhythm and I couldn’t find who produced it, and nobody at the studio knew who produced it. So, I just kind of forgot about it, and then somebody brought me to Penthouse studio to meet some German producers one night and Marcia Griffiths was working there, and I think Exco Levi. So I saw them, and he has a MP3 player with some rhythms, so he gave me the headphones and say, “Listen and tell me which one you like,” so I was skipping through and when I found the rhythm, I was like, “Yo, shit! I have a song written for this already.” He was, like, “No, that’s not possible,” and I’m like, “Yeah! I have a song written for this already! Been looking for you guys for years.” And that’s how “Smile Jamaica” was recorded. It’s one of those songs that just, from you hear the music, it just came, almost like it was in the music already. And I had it written, not down in words but I recorded a voice note of it on my phone and just had it, and then we went to the studio the day after and recorded two songs, “Play Some Roots” and “Smile Jamaica.”

I already had the lyrics and already knew the rhythm, because I was at Kings of Kings studio a very long time before I recorded the song, like maybe two years, and found the rhythm on the desktop, and I didn’t realize until later that it was Lutan Fyah who was recorded on the rhythm. And I went home and wrote the song to the rhythm and I couldn’t find who produced it, and nobody at the studio knew who produced it. So, I just kind of forgot about it, and then somebody brought me to Penthouse studio to meet some German producers one night and Marcia Griffiths was working there, and I think Exco Levi. So I saw them, and he has a MP3 player with some rhythms, so he gave me the headphones and say, “Listen and tell me which one you like,” so I was skipping through and when I found the rhythm, I was like, “Yo, shit! I have a song written for this already.” He was, like, “No, that’s not possible,” and I’m like, “Yeah! I have a song written for this already! Been looking for you guys for years.” And that’s how “Smile Jamaica” was recorded. It’s one of those songs that just, from you hear the music, it just came, almost like it was in the music already. And I had it written, not down in words but I recorded a voice note of it on my phone and just had it, and then we went to the studio the day after and recorded two songs, “Play Some Roots” and “Smile Jamaica.”

“Here Comes Trouble” made this massive impact, and on “Capture Land” you just crystalize some very important issues in Jamaica that also relates worldwide with colonialism and neo-colonialism, and the displacement of people.

Yeah, it’s spiritual music, you know? It’s music that somehow explains what you are experiencing in life today. I try to explain it to myself, because I, too, like everyone else is trying to understand what’s going on. Like, for instance, I don’t really know what’s going on, so I depend on the music and the songs to kind of explain it to me, you know? And to somehow explain it in a spiritual way that even I have to listen to the songs and try to find the meaning in it. So that song was produced by Winta James.

One of the more talented people producing music right now in Jamaica.

Yeah man, a real talent, and a true musician.

So with the new album, I wanted to ask a bit about your feelings about the album, the motivation behind the album, what you’re really trying to express on the album. And I noticed that, as has been the case with your mixtapes or your previous releases available online and so on, there’s a mix of old and new material, where it’s mostly new, but including some tracks that have been around for quite some time. So I wanted to hear your thoughts about that and the whole process of putting the album together.

Well, you know, our work is a continuous work and that’s why it will always have that kind of continuity in it where the music, it kind of links from that time to now. I’ve been working on this album from I just started, from when I linked up with Teflon first, the first thing, when I started to release music as Chronixx, the first thing we decided to do was to make an album. So it was from that time that I started to write some of these songs, and had an idea of how I wanted it to sounds, and all of that. So now it’s just the opportunity to do it.

I’ve been working on this album from I just started

I’ve been working on this album from I just started

So opening with “Spanish Town Rockin,” it’s a song that a lot of us have loved for quite some time, and as with “Majesty,” one of the compelling things about it is that they’re both referencing the great reggae of the past, but then it’s forward facing, not “retro.”

Yeah, because, I mean, we put weself into it and we are young people, we are the youths of Jamaica, so we are the youths in reggae music. So it reflect that. And for me, my love for music is not really a kind of fanatic kind of love where I do roots reggae music out of fanaticism and out of obsession, I do it because it’s my natural culture, and it’s my natural state of being in music. So, hence, why it happens so naturally is, like, when I hear…as I say, I started my first experience with creating music was with Studio One music, a lot of music from out of all of these legendary studios you’re talking about. My first dancehall rhythm was King Jammy’s dancehall rhythm that I made music on, so me is from that time there.

And as you said, the song “Likes” is a very dancehall-oriented rhythm, and then the subject matter, you’re sort of flipping the whole social media thing and revisiting that through a Rastafari perspective.

Yeah, it’s just through the perspective of us being spiritual people and musicians who, no matter what, we have to practice music in its truth. Like, you can’t pretend to practice music, you know? So you have to do it wholeheartedly and you have do it fully. So that’s where the whole lyrics come from. It’s about us as young musicians, like in 2017, we live in a very confusing time where you can end up feeling very gratified by the amount of traction that you build up from social media, and whatever, but really and truly, if you are not making the best music that you can, then what is people really following? What are they following? Are they just following a sensation, or are they following a sensational musician? It’s two different things. So we just ah outline the difference.

There’s a range of themes and feelings on the album, a range of moods. You’re going from almost a militant message on “Black Is Beautiful” and “Selassie Children” is in a roots anthem mode, hearkening to those classic Rasta tunes of the 70s, and at the same time, “Skanking Sweet” is like a lover’s rock style, and “Christina” has another feeling again. You almost veer into pop territory at one point, and then dancehall on another side. What can you say about that range on the album?

That range, that’s more than a range, man. That is a discovery, or a defender, or one of them things, bigger than range, man. But anyways, I’ve just been doing a lot of different music, and then from touring and all of that, travelling all over the world and making music, you know, I ended up being exposed to many different sounds that really resonates with me. That’s how I end up doing all of this different kind of music. That comes from me sharing stages with various artists around the world and working with people like Joey Badass, Maverick Sabre, and also that variety and that versatility comes from me working with artists such as Sly and Robbie, Inner Circle. So imagine now, you are in the studio with so many different kinds of people, doing shows with reggae artists and musicians from around the world, a lot of blues musicians, a lot of folk musicians. So it’s like, yeah!

So you’re absorbing some influences?

Yeah, definitely. Cause I’m a musician and I have to learn, and if the universe place me in a position to learn, I can’t reject what the universe is trying to make me see. Like I can’t pretend that I didn’t watch James Day perform, can’t pretend I didn’t watch the Roots band play and I didn’t watch Erykah Badu perform live, I can’t pretend as if I didn’t do the Governor’s Ball with Rae Sremmurd and all of them people there, and I can’t pretend that I didn’t work with Diplo and Major Lazer and all of them people. So it’s like it’s the most powerful force in the universe that drives us as humans, and sometimes we reject it. Like, we will be in a place and totally reject what we are there to learn, you know? But I like it. Love it.

What about your promotion with the Addidas Special range?

I don’t really have a lot of comment about it. It’s a very good thing. I’m mainly working with someone who loves our culture and who understands Jamaican music culture and appreciates it, so that’s a good thing.

With the album, it must have been quite a composite process, because you recorded it in so many different places, especially at Circle House with the great Inner Circle, and a place where so much hip-hop has been laid down as well as reggae, and you’ve got Donald Kinsey on a couple of tracks.

Yeah, Donald is such a great musician. That part was like a dream, having him do that album. It was a great process and Donald Kinsey, for instance, played on a lot of reggae music but he’s a blues musician, a blues guitarist by heart, so that’s what he naturally played. It was good working with him and getting a feel of what his music feels like, and how it sounds alongside our music.

I’m going to be producing a lot of music with a lot of different artists

I’m going to be producing a lot of music with a lot of different artists

What are you working on right now, and what can we expect from you in the future?

What I’m working on now is trying to produce more, music that I can hopefully do with other artists. I didn’t do a lot of collaborations on the album, because I think, where I’m going next with music and with production and all of that, I just didn’t feel like I necessarily have to…I just feel like, “Yo, time for some new shit.” You know? So right now, where I’m going next is I’m going to be producing a lot of music with a lot of different artists. I feel that’s the next step for me. So let’s just see how that works.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z