Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

"Get Up, Stand Up": The Noble Truth Of Rastafari

"Get Up, Stand Up": The Noble Truth Of Rastafari

“The First Noble Truth of Rastafari, then, was to assert the dignity and individuality of Black people in the Americas.”

“Now this, monks, is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: It is this craving which leads to renewed existence, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence, craving for extermination.” Buddha In many ways, the Rastafari worldview resembles Buddhist teachings that humankind is caught up in samsara—a state of desire and craving for temporary, compounded things, and that the way out of samsara is nirvana—the cessation of desire. To overstand Rastafari, substitute samsara for Babylon; for nirvana, Mount Zion. So where many see order, Rastafari discerns slavedom; where many see power and success, Rastafari perceives vanity and a “chasing after the wind.”

But whereas the Buddhist monk turns his gaze inward to root out the grasping self, Rastafari envisions itself in a battle for the hearts and minds of the “lost Ethiopians” and against the powers and principalities of Babylon the Great. For Rastafari, the way out of Babylon is by waking up to the true self (InI) and the path to redemption begins with the most downpressed of Plantation America—the sons and daughters of former slaves. “The First Noble Truth” of Rastafari, then, was to assert the dignity and individuality of Black people in the Americas. Much of the spreading of this “noble truth” has been done by Bob Marley and the Wailers, and in the song, “Get up, Stand up” co-written with Peter Tosh, the themes of spiritual blindness, the need for personal dignity, and a call to action—to oneness, if you will—emerge from the lyrics.

“Preacherman, don’t tell me,/Heaven is under the earth./I know you don’t knowWhat life is really worth./Its not all that glitters is gold;/half the story has never been told” (“Get up, Stand up”). The Christian church and Roman Catholicism, in particular, have been the favorite targets of Rastafari and Marley. In “Talking Blues” Marley proclaims, “Cause I feel like bombing a church, now that you know that the preacher is lying.” And what are the truths that the Church, the state and the media have been hiding from the people—“the half that’s never been told”? “Almighty God is a living man” (“Get up, Stand up”). This “revelation” of Rastafari is not exclusive to the person of Haile Selassie whom Rastafari during the fifties and sixties regarded as Jesus Christ incarnate, but also the divinity of mankind expressed in the concept of InI. The “half that’s never been told” extends to knowledge about slavery, Maccabean history, and the coronation of Haile Selassie. The lack of knowledge or resultant spiritual blindness, according to Rastafari, is a vast conspiracy of the slave drivers and Babylon because the only way to keep “the children” in virtual slavery is to blind them to the truth: “No chains around my feet, but I’m not free/I know I am bound here in captivity” (“Concrete Jungle”). The way out of Babylon is knowledge—overstanding—because not even in language (a key tool of liberation for Rastafari) is man ever an object (“I” not “me”), not under (“over”-stand” not “under”-stand”) anything. But knowledge is only the first step, “Now you see the light/ Stand up for your rights.” From Rastafari’s first noble truth of the sanctity of the indwelling god, follows Rastafari’s insistence on the inviolability of human rights: “Every man got a right to decide his own destiny/ And in this judgmant there is not partiality” (“Zimbabwe”).

The Rastafari path to freedom is found in action, in the assertion of individuality, and resisting all attempts by Babylon to deny one’s divinity: “Life is your right.” And it will always be a struggle because at every turn Babylon seeks to blind Rastafari or “the son’s of light” by lies and Nixonian politricks, “You can fool some people some time,” or by “bribing with their guns, spare parts and money/ Trying to belittle our integrity” (“Ambush in the Night”). But how far should one go in defending one’s rights? Bob struggled with this question for a long time and in “One Love,” he answers in the language of Rastafari eschatology: “Let's get together to fight this Holy Armageddon.” But when faced with an implacable enemy, he asserts, “And brothers, you're right, you're right, /You're right, you're right, you're so right! /We gon' fight (we gon' fight), we'll have to fight (we gon' fight), /We gonna fight (we gon' fight), fight for our rights!” (“Zimbabwe”). The Rastafari worldview (unlike the Buddhist disdain of outward actions that lead to further karmic entanglement) is not passive because given the experience of Black people in the West individual freedom is never granted, it has to be won. Every day. At the core of this conflict in the Rastafari I-niverse is a struggle for life and death. For whereas the Church and politician teach “heaven is under the earth”—you’ll get your rewards when you go to heaven—and bamboozling with “isms and skisms” of racism, classism, capitalism and socialism: “We’re sick and tired of your ism skism game/ die and go to heaven in Jesus’ name,” Rastafari places its trust in a Mount Zion that is not in some far off time, space and place: “Most people think,/Great God will come from the skies,/Take away everything/And make everybody feel high” (“Get up, Stand up”). Rastafari is a faith of the present tense”: But if you know what life is worth, /you will look for yours on earth:/And now you see the light, /You stand up for your rights. Jah!” (“Get up, Stand up”). Heaven is right here, right now or as The Gospel of Thomas states, “But the kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and men do not see it.” “Get up, Stand up,” which has been used as anthem for the dispossessed by Amnesty International, was one of the signature songs that came of out Bob’s collaboration with Peter Tosh, and their relationship could be compared Lennon and McCartney. Like McCartney, who ostensibly believed in love and revolution, Bob liked to stay away from controversy that would hurt record sales. However, Peter, like John Lennon, was always pushing his friend into areas that we would normally go. I’m almost sure that “die and go to heaven in Jesus’ name,” belongs to Peter because in live concerts, Bob would shy away from the lyric and sing, “We’re sick and tired of your ism, skism, / die and go to heaven in ism, skism.”

It is also interesting to note that Bob was baptized into the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and accepted the name Berhane Selassie, “Light of the Trinity” before he made his transition. Despite the irony that time plays even with great artists like Marley, “Get up, Stand up” remains a remarkable lyric whose greatness lies in the assertion of a truth that goes beyond Rastafari (forgive me idren) and any religion: “Life is your right.”

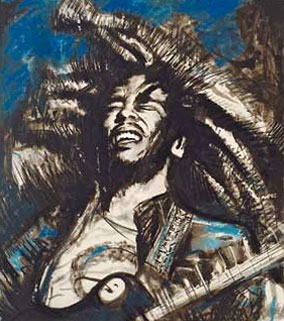

Art: Get Up Stand Up By Ronnie Wood

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z