Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Tiken Jah Fakoly Part 2

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Tiken Jah Fakoly Part 2

Interview: Tiken Jah Fakoly Part 2

"When I went to Jamaica the first time and left the airport, it was just like in Abidjan or Bamako"

Sampler

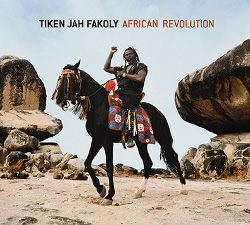

In part two of our interview with the Ivorian Prince of Reggae, we talk about musical influences of Tiken, his new Album 'African Revolution' and his experiences in working with Sly & Robbie. We touch the delicate question of repatriation, where Tiken Jah gives a surprisingly different answer. And we talk about threats against him.

Alpha Blondy used to be the superstar of the youths of West Africa. You have replaced him pretty much, being the spokesperson of the African youths now.

That’s a big responsibility for me. The youths respect me because I never changed, I didn’t go with the politicians, I didn’t ask for money in the president’s office. I didn’t change my message. I hope I’ll have the energy to always continue my fight. For me, that’s the real Reggae music, the people’s voice. It’s important for me to follow Bob Marley’s road, being with the sufferers. That is the mission of Reggae.

When relaxing at home, what music are you listening to?

Jamaican Reggae. Bob Marley every time, you know. He’s our prophet. I listen to Peter Tosh. And I listen to a lot of Mande music, traditional African music, because I always want to create original Reggae music. Reggae music is African music, because it has been created by African people in Jamaica. But we in the Motherland are obliged to do something different, so I add traditional instruments.

The youths respect me because I never changed, I didn’t go with the politicians, I didn’t ask for money in the president’s office

The youths respect me because I never changed, I didn’t go with the politicians, I didn’t ask for money in the president’s office

Which African artists do you prefer?

Salif Keita, Mory Kante, Amy Koita, Oumu Sangare. But I also listen to young artists, like Sizzla and Capleton from Jamaica. Actually I listen to a lot of different music. Indian music [laughs]. I want to have inspiration, you know.

With which artist would you like to record a combination?

With Damian Marley, for example. I invited him to record a tune with me for African Revolution, but it didn’t work out as he was busy touring. I really respect his works. But I could do combinations with everybody. A combination tune is exchange between two artists. Take Damian Marley. He’s not well known here, people know he’s the son of Bob Marley, that’s all. So he could profit from my popularity here, as people would say “you know, he did a tune with Tiken Jah”. But in America or Jamaica, people would say “that’s the guy who sang that tune with Damian Marley”.

Tell us about your upcoming album African Revolution.

This album is talking about African intelligent revolution. We need to build up, not to break down. Too many young Africans have been killed, we don’t want to kill anybody. No bloodshed. But we can do our revolution going to school.  Our children have to study to understand the way the Babylon system works. We need to know the system. The intelligent revolution is about unity, too. We need to speak with one voice. One economical power, one political power. So this album is talking to Africa’s youth. In the last album, I talked about being proud of being African. Now I say yes, we are proud to be Africans, but that is not enough. We are proud to be Africans but we have to fight to get all the things we want. All the young people here want to go to Europe, to America. I tell them that nothing people have there is coming from the sky. People fought there to get what they have today. God gives us the sunshine and the rain. It is never really cold in Africa. We can fight to get it all, too. Nobody will change Africa for the Africans. If we want to change Africa, we have to fight for it. If we want to change this continent, there’s a price to pay for that. This price is the revolution.

Our children have to study to understand the way the Babylon system works. We need to know the system. The intelligent revolution is about unity, too. We need to speak with one voice. One economical power, one political power. So this album is talking to Africa’s youth. In the last album, I talked about being proud of being African. Now I say yes, we are proud to be Africans, but that is not enough. We are proud to be Africans but we have to fight to get all the things we want. All the young people here want to go to Europe, to America. I tell them that nothing people have there is coming from the sky. People fought there to get what they have today. God gives us the sunshine and the rain. It is never really cold in Africa. We can fight to get it all, too. Nobody will change Africa for the Africans. If we want to change Africa, we have to fight for it. If we want to change this continent, there’s a price to pay for that. This price is the revolution.

How can this change, this revolution actually be done by the people?

The first thing we have to know is that we are all brothers. We are all victims of the politicians, so we have to unite to fight against the politicians. For me it’s very, very important to begin the fight. The new generation will continue it. African unity is impossible today. Young people, little boys are asking me on the street to give them money. I tell them, work for me and I’ll give you money. I ask the boss later if they worked, and if they did I pay them. If they didn’t I tell them to go home. We have to wake up. Nobody will give us our rights. We have to fight for them. That is my message in the African Revolution album.

With who did you worked on this album?

I wrote some lyrics with some artists in France, like Féfé. I can write and compose myself, but I’m very popular today in France, some people in Germany know me. So it’s important to write lyrics in a way that people there can listen to them. We worked with some Jamaican musicians. The drummer tours with Shaggy. Glen played the bass, he’s big there in Jamaica. Sticky, Bob Marley’s percussionist, did the percussions. We went to Bamako to record traditional instruments like the kora. Petit Conde from Guinea played the Mande guitar. We didn’t work with Sly & Robbie this time because we did the last two albums with them and wanted some variation. Maybe we’ll work again with them one day. Jonathan Quarmby and Kevin Bacon from England arranged the album. They worked with Ziggy Marley on his album that won the Grammy. We had a good team for this album, I’m very happy.

What was working with Sly & Robbie like?

It was very relaxed for the second album, Coup d’Gueule. But it was hard for the first album we did together, Françafrique, because Sly didn’t arrive in time. We met at ten a.m. on the first recording day in studio in Kingston. Sly said he would be there in 30 minutes. He was in Miami and arrived three days later. But when he arrived and started to play, I forgot everything. They are great musicians, it’s everybody’s dream to work with them. It was my dream and I did it! And I’d like to work with Tyrone Downie again. I did two albums with him, too.

Sly said he would be there in 30 minutes. He was in Miami and arrived three days later

Sly said he would be there in 30 minutes. He was in Miami and arrived three days later

Where was African Revolution recorded?

We began working in Paris, in the studios De La Seine. We did the programming there. We continued in London, working in the Rock studio. After that we went to Tuff Gong Studio in Jamaica, then to H. Camara, my studio in Bamako. Then we went back to London for a month of mixing! The mastering was done in the US, but I don’t know where exactly. My artist director went there.

What are your impressions when comparing life in Jamaica to life in West Africa?

The way of life is the same, I’d say. When I went to Jamaica the first time and left the airport, it was just like in Abidjan or Bamako.  People where coming, asking “do you want a taxi?”, “do you want some Ganja?” or “do you want some whatever?” I respect this song from Alpha Blondy called Afriki. [He sings] Jamaica ye ah, Afriki le ye. It’s really like that. Last time I was in Jamaica, in February, we bought some fish in the streets and ate it on the road like in Bamako, you know. Nobody knows me as an artist in Jamaica, so I was free. Jamaica is Africa, because people there live like in Africa.

People where coming, asking “do you want a taxi?”, “do you want some Ganja?” or “do you want some whatever?” I respect this song from Alpha Blondy called Afriki. [He sings] Jamaica ye ah, Afriki le ye. It’s really like that. Last time I was in Jamaica, in February, we bought some fish in the streets and ate it on the road like in Bamako, you know. Nobody knows me as an artist in Jamaica, so I was free. Jamaica is Africa, because people there live like in Africa.

What do you say to Jamaican Rastas who want to repatriate to the Motherland?

It’s a nice idea, but I don’t think it’s possible. Repatriation should be spiritual, not physical. We are very proud to have black people everywhere in the world. I’d never say that slavery was a good thing. But I say, look at Barack Obama being the president of the USA, nobody would have thought that was possible just five years ago. This is something positive. When I go to Jamaica, to Martinique, to Guadeloupe, to St. Lucia, all over the world you have islands with black people. Today, nobody could bring them to Africa. And Jamaican artists shouldn’t just talk about Africa all the time. I hope they will come to Africa to learn to know it and to play there. They can encourage Africans to love their continent.

Repatriation should be spiritual, not physical

Repatriation should be spiritual, not physical

Have you performed live in Jamaica?

No, never. I should have done that once five years ago but it was cancelled. I would have performed in Haiti first, then proceed to Kingston, but there was a revolution going on in Haiti so we couldn’t go. But I’d really like to play in Jamaica and build a school in Trenchtown because I know they need that.

Right, your campaign “Un concert, une école”.

I started this campaign in France, where I did two shows to build two schools in Africa. And I wanted to play concerts in Africa to build schools in Africa to show that we can help ourselves. The West isn’t going to help us. It’s part of the African revolution, you know. We did it, but didn’t get any money to build the schools. I will continue. I just need sponsors. My dream is building one school in every African country before I die. I hope I’ll have the energy to get there.

Do you prefer working in the studio or performing live on stage?

Performing live, definitely. Performing live is like a political rally for me. I meet the people and tell them what I want to tell them. Live and direct.

Would you say that Côte d’Ivoire’s thriving Reggae scene is more creative than today’s Jamaican one?

No, not really. Nobody can play Reggae music better than Jamaican people. Bob Marley once said in an interview that Reggae music would return to Africa one day. And today, you can find the real message in African Reggae. You know, the Jamaican artists are fighting for Grammy awards now. They want to be famous in America and try to please the American audience. The real fight is led by African Reggae. We have a mission, talking about the majority of the population that is suffering.

You will soon open a Reggae club here in Bamako?

We need a Reggae club here. I am living here for eight years now and wanted to put Bamako on the Reggae map. If you go to Bamako and want to listen to Reggae at two o’clock in the morning you’ll come here, to Radio Libre. I’ll perform here and many others, too. The particularity of this club is that you can easily record all live music here as the studio H. Camara is just downstairs. There is a connection between the studio and the club.

You’re living here in Bamako for eight years now. A couple of weeks ago, somebody intentionally burned down two of your cars and tried to set your home on fire. Are you still feeling safe here?

Yeah, I’m safe in Bamako. I like to live here with the people. I don’t want to be protected like a president. I have more security guards now, but I don’t want to live with bodyguards everywhere. But I’m not afraid. I have an enemy somewhere who can’t talk to me because I’m a lion, so he comes at night and sets fire to my house. He should come to me and talk or fight with me.

Why would somebody hate you that much?

I don’t know, I really don’t know. But I know it’s nothing political, I don’t have any problems with the government of Mali. If he reads your magazine, he shall come and face me personally!

Thank you very much for the interview, Tiken Jah!

Thank you very much! Big up United Reggae.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z