Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Eric Monty Morris

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Eric Monty Morris

Interview: Eric Monty Morris

"I think the world still wants ska"

Sampler

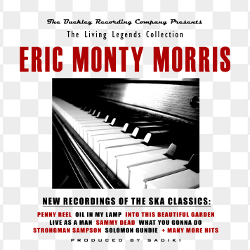

Elder statesman of ska, Eric “Monty” Morris, was born in St Andrew Jamaica on July 20th 1944. The young Monty loved music and could often be found at the sound system dances of the 1950s when US style R&B was the order of the day. Like many fellow legends of the period, such as Alton Ellis and Eric’s friend and neighbour Derrick Morgan, he was a contestant on Vere Johns’ Opportunity Hour talent show, and began a recording career in 1959. He voiced for Duke Reid, Prince Buster, Byron Lee and Clancy Eccles, repeatedly topping the Jamaican charts. In 1964, riding on the success of singles Sammy Dead Oh and Oil In My Lamp, he joined an excursion to the New York World’s Fair, organized by Edward Seaga, to sing with Byron Lee and the Dragonaires. Sadly, ska failed to capture the imagination of the American public until after the movement had ended, while the “Wild West” mentality of the Jamaican music business, coupled with the singer’s soft temperament, left him short of the financial rewards gained by some of his peers, so in 1970 he retired to the United States. Yet his memory burned strong the minds of the US Caribbean community and he was eventually tempted back to record for the Washington DC Kibwe label in 1988. 1999 even saw a triumphant return to Jamaica after 3 decades for the concert series Heineken Star Time. Ten years later Morris’ son Reuben introduced Monty to the singer/producer Sadiki who became his manager. Together they have created The Living Legends Collection – Morris’ first ever full length album, bearing recuts of his hits - and just a few days before its release Angus Taylor got the chance to speak with the great man himself…

How did you get the name Monty?

That name was originally given to me by my mother. She just decided to call me Monty. It was just a little nickname, a blessing name that I grew up with.

You were friends with Derrick Morgan and lived near each other on Orange Lane, Kingston.

Derrick and I really moved good as individual artists from Jamaica. In the early times before Derrick even came into the music business I called his attention to music. Derrick wasn't really a direct singer but through our being friends from in the lane, I called his attention to it and showed him to auditions. So we move good still, but in terms of recognition for the works that you do, they hardly even mention me. I have to really put myself out there so a man will recognise me for my work.

Tell about how you started on Vere Johns opportunity hour with Derrick.

I saw the Vere Johns Opportunity Hour by looking in the Star newspaper clippings. I was doing a little job at a window sill when I saw this clipping for Vere Johns Opportunity Hour at the Palace Theatre advertising for dancers and singers. So I called Derrick’s attention to it – because both of us were practising - and said, “Derrick, let’s go to the Palace Theatre and take a look at the show”. So from there I tried travelling on to see how far I could go in the music business and eventually I ended up being a recording artist.

I saw this clipping for Vere Johns Opportunity Hour at the Palace Theatre advertising for dancers and singers. So I said, "Derrick, let's take a look at the show"

I saw this clipping for Vere Johns Opportunity Hour at the Palace Theatre advertising for dancers and singers. So I said, "Derrick, let's take a look at the show"

Derrick had already recorded for Duke Reid but you voiced your first recordings - Now We Know and Nights Are Lonely - for Simeon Smith's Hi Light label?

Yes Hi Light! Mr Smith! He used to have a little record store at Spanish Town Road and that was where I did my first recording with Derrick – We Want To Know Who Rule This Great Generation [Now We Know].  The entertainment business on the stage wasn’t too prosperous for me so I started to do recording. I think it’s only because of my versatility within the music business why I got some support from these promoters. I had to make it on my own. I had to go out and show my talent to these promoters instead of them coming looking for me. Those other guys, they would come and look for them.

The entertainment business on the stage wasn’t too prosperous for me so I started to do recording. I think it’s only because of my versatility within the music business why I got some support from these promoters. I had to make it on my own. I had to go out and show my talent to these promoters instead of them coming looking for me. Those other guys, they would come and look for them.

You started recording when the pre ska R&B was very popular.

Yes, the boogie woogie music was around before the ska developed. I kind of slightly changed the trend of the dancing that was going on in Jamaica. I feel we, more or less, tried to create something of our own instead of keep dancing off those boogie woogie tunes we would get some kind of identity about our own music. That's why Jamaican music is kind of different from all other music.

I had to make it on my own. I had to go out and show my talent to these promoters instead of them coming looking for me

I had to make it on my own. I had to go out and show my talent to these promoters instead of them coming looking for me

Tell me how you came to record for Prince Buster? You cut Humpty Dumpty in 1961 which was a big hit. It was kind of half-way between the boogie and ska?

That was quite a historical event now because, as you say, the boogie beat changed over. You used to have a whole heap of boogie tunes when I was a young boy going to sound system dances. I'd been going down to Orange Street where they had all the record shops and sound systems going on and they started to recognize me as an artist. It happened through Derrick Morgan. Derrick was on the Lane where I lived so Prince Buster would come down there and said, "Monty, that guy is a good singer. I'm going to give him a trial". So I eventually found myself ending up at the studio with a couple of songs, Money Can't Buy Life and Humpty Dumpty and a few more tunes didn't make it onto 45. So they found out I had a good voice and could sing. It turned out that that tune kind of changed the trend of music in Jamaica because eventually - apart from one or two tunes - the boogie woogie things cut out and it was just ska.

As well as R&B and Nursery Rhymes, the other music from the 50s that gave you inspiration was mento and gospel. Some of your full ska recordings from the 60s like Penny Reel (for Duke Reid) and Sammy Dead (with Byron Lee) are old folk songs, while Oil In My Lamp is an old Christian hymn.

As a ska artist I tried to be an individual versatile artist so I'd record a little soft tune, or a mento or calypso style. So I did those kinds of songs there in a mento style of singing like Penny Reel, Oil In My Lamp - in a Jamaica style. And I've still got a couple of those tunes inside of my brain that I haven't recorded yet!

Oil In My Lamp and Sammy Dead Oh were also big hits. Tell me about your subsequent appearance at the World's Fair in New York in 1964 with Byron Lee and the Dragonaires.

That was a great high-lighted time in New York. But every man did their own thing. I went there with Byron Lee, thinking they would look out for my rights as a singer coming up. But every man there looked out for their own thing in those times for the recognition of the ska. At that time I did the tune Sammy Plant The Corn [Sammy Dead Oh] and it was getting a lot of interest. They couldn't stop the tune Sammy from being a hit song but they never really put the interest inside my thing to make me known so that I was in the spotlight. But everything is good because the Father bless and I am still going on keeping these things alive.

During the rocksteady era you recorded tunes like Put On our Best Dress for Mrs Pottinger and then, in 1967, another cutting edge tune Say What You're Saying for Clancy Eccles. How did that come about?

Duke Reid had just built his studio at Bond Street so Clancy came straight up to my yard to look for me and told me to come to the studio because he had a session going on. Because in those times we were all still trying to create and trying to change the mood. They had the rocksteady band going on with Tommy McCook and all those guys so I went down to the studio and fortunately Clancy got a very good tune out of me (because I always try to have something reserved in the bank!) so I put that tune down as well as Tears In My Eyes. Tommy McCook and the band was kicking too in Duke Reid's new studio upstairs.

I feel Say What You're Saying is the first reggae tune to ever come out

I feel Say What You're Saying is the first reggae tune to ever come out

Some people have said Say What You're Saying was the first reggae tune.

Oh yes! I feel Say What You're Saying is the first reggae tune to ever come out. People say Larry Marshall sang Nanny Goat and Larry Marshall told everybody, "I made the first reggae tune". But Larry Marshall was in that session with me and out of the tunes that were sung that day, Say What You're Saying was the best tune of the session, which turned out to be the first reggae tune. It had a different flavour from rocksteady. You had ska, rocksteady, and then reggae - each had a different little taste in terms of the timing of the rhythm and the things the musicians would play. But as an artist I just let other people look at the music and say what they feel.

Why did you move to the United States in 1970?

It was a hard time in Jamaica for a man of my talents. It was through my mother. She saw the hard time I was getting and said, "Monty, we go try it. It will be a trip. It will be a visit". She found a better life. But I never really came over to the United States with a singing intention. I worked a few jobs over here but eventually in a man at Lion and Fox Studios in Washington DC said, "Monty, I remember you were one of the legendary singers from Jamaica" and things like that so I found myself doing one or two shows and cut some dubplates. I went back into the studio and tried to do back a couple of my longtime songs and they put them on a big disc and released them so I started off again. [The album In Cry Freedom was a collaboration between Monty and Ras Michael’s son Michael Enkrumah released on the Kibwe label in 1988]

How is it that in 50 years, with all these big singles you never recorded a full album?

That is a very important question, sir. This is just the reason why I made this little move with Sadiki because I think it is a very important thing to have him looking over everything. It was a family member that said, "Well, Monty, give him a try and see what you can get out of it. Because all these people you do music for for all these years and none of them even think of saying what happened to all them tunes you sing on when they sell and this and that. Give him a try and see if things come together. It might start anew and change for the better". I don’t want to keep doing these things over and over, put the talent out and don’t get any redress for doing it. Because a lot of those guys I did recording for, when I take stock, after the music would start to sell they wouldn't confront me with what was going on. So now is the time that I should really be putting everything in one place and keep doing the things for one label and one person for all of the things I was doing before.

A lot of those guys I did recording for, after the music would start to sell they wouldn't confront me with what was going on

A lot of those guys I did recording for, after the music would start to sell they wouldn't confront me with what was going on

Why did you decide to record your old hits again instead of new material?

I feel good about it because Sadiki put a different change on it and made it sound more original. It was a good move we made to do back my old tunes in a different new kind of beat and add something to it. I love the way how he does his things.  I have some new songs and we will do another album soon, but I’m going do it in the style like we used to do it with some live musicians, some rhythm men - a rhythm section.

I have some new songs and we will do another album soon, but I’m going do it in the style like we used to do it with some live musicians, some rhythm men - a rhythm section.

Which musicians and singers do you rate today?

The musicians that really have the sound of today are men like Dean Fraser, Ernest Ranglin and Gladstone Anderson. They still have that touch and feel for the music that comes from Jamaica. They haven't lost that feeling. Beres has still kept that feeling as an icon and Marcia Griffiths, and I can't throw out my brethren Derrick because Derrick is always a round and about man. A man who can sing any kind of music. I've talked to Derrick a few times when he has been to Miami because he is a man who is moving from one place to the other.

What do you think of how popular ska music has been outside Jamaica over the years? Are there any new ska bands you like?

I feel like ska music doesn't really reach the people in the right way but I feel there is something still there in the ska music. I see them dancing in the real way towards the music when they hear it now but it's like they don't really understand it the way the musicians and the singers really know. But I think the ska is still here and still has something to deal with within the music. So in parts of the world where they hear the real ska and hear me or other artists that have the legend, they are going to realize that the people who were individually responsible for the music - the creators, the people who really started this thing - still have it going on. Half of the world still wants to feel the reggae and ska and the other half of the world doesn't know about it so I think the world still wants ska.

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z