Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

Interview: Fashion Records

- Home

- Articles

- Interviews

- Interview: Fashion Records

Interview: Fashion Records

"Chris is musical, I know how the business side of it works. We complemented each other in that way"

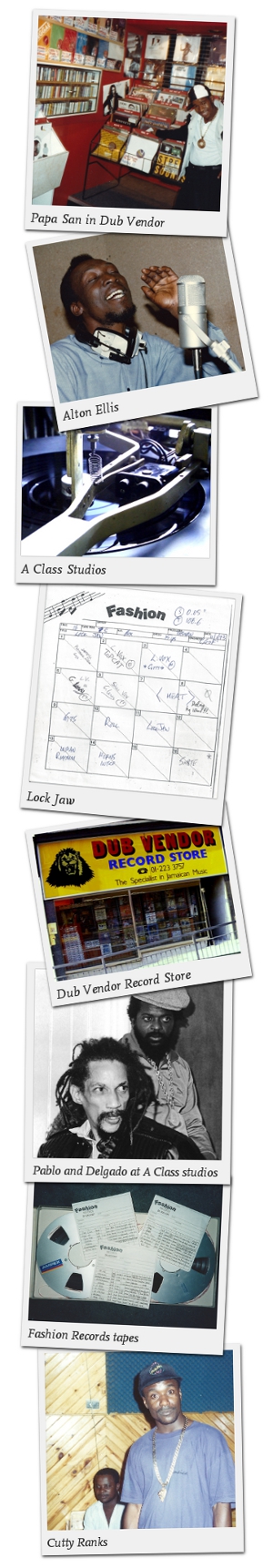

Sampler

On 19th March the seminal UK reggae label Fashion Records began reissuing its back catalogue via online distributor Believe Digital. Founded by two schoolfriends John McGillivray and Chris Lane (who together started the Dub Vendor record retail empire from a Clapham Junction market stall, selling pre release 45s) Fashion's debut single, Dee Sharp's cover of Leo Hall's Let's Dub It Up, took the UK reggae chart's number one spot in the summer of 1980. Two years later John and Chris set up their first of several South London premises titled the A Class studio cranking out superlative contemporary reggae in all forms. From UK deejay classics like the late Smiley Culture's massive 1984 hits Cockney Translation and Police Officer to lovers fare by Nereus Joseph and Maxi Priest, the duo showed an unerring versatility and reactivity to what was happening in dances in the UK and Jamaica, navigating through the digital revolution and even putting out jungle tracks in the 1990s as their own works got sampled and set to 140bpm. By that time Fashion had a strong link with Donovan Germain's Penthouse Records, and had kick-started the careers of apprentice-engineers-turned-producers Gussie P of Sip-A-Cup and Frenchie of Maximum Sound.

In the new century the label wound down, but following the closure of the final Dub Vendor store last year the time seemed apt for Fashion to make a comeback. Angus Taylor spoke to Chris and John at John's offices above the shop about their roles one of UK reggae's historic imprints and the heady times in which they plied their trade...

Chris and John, how did two seventies schoolboys become such big reggae fans?

Chris: At that time everyone was being skinheads. Reggae was the fashionable music at that time, so we just developed a friendship over that. Really we were some of the few kids who didn't give up on reggae when we started wearing flares. Skinhead wasn't really a movement, it was just a fashion. When everyone started growing their hair longer and wearing different clothes 99% of skinheads went off and listened to the Faces and David Bowie but me and John didn't.

By the time Fashion started Dub Vendor had grown from a stall in Clapham Junction via the short-lived shop in Peckham to the two main shops in Ladbroke Grove and then Clapham Junction. Why did you decide to start the label?

John: I put out a couple of tunes from Jamaica for Gussie Clarke on the Dub Vendor label. Dub Vendor needed more of a presence in the marketplace because even when we were a stall we were kind of batting above our weight, advertising in Echoes as if we were a big thing when we were a one-day-a-week market stall (laughs). Chris by that time had a dub-cutting machine and he'd produced a couple of tunes for a friend of ours, Dave Henley with the group the Investigators, under a different name, The Private Eyes. Having heard what he did on his own I thought "You know what? We could do something together".

Both me and Chris knew that Let's Dub It Up was ripe for doing over

Both me and Chris knew that Let's Dub It Up was ripe for doing over

Your first tune hit big - luck or skill?

John: I found Dee Sharp through my girlfriend at the time, now my wife. A friend of hers at work was going out with him and said that he could sing. Both me and Chris knew that that Let's Dub It Up was ripe for doing over. The great thing about the reggae market then was that it was a definite market, so it wasn't like you were making things and experimenting, there was an audience there and they were hungry for stuff to be supplied to them. If you hit it right you weren't going to sell millions, but you knew you could sell thousands if you got it on point. So the easy way at the start was doing over songs that you felt were in demand. You'd be in the shop and people would ask for those things or you'd hear them still playing in the dance or whatever. That was really where it started from. There wasn't any great plan.

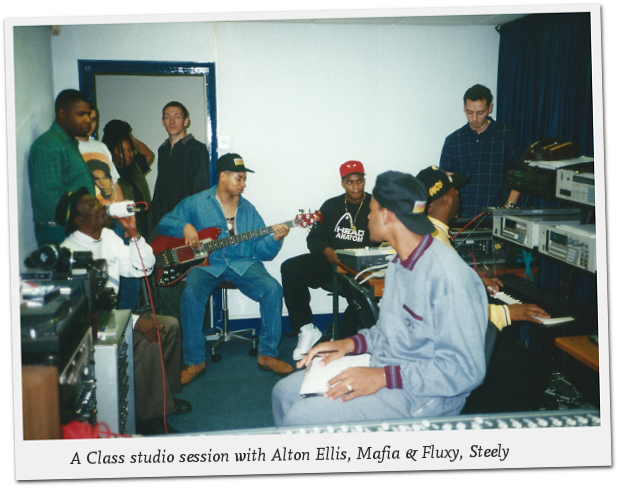

You started your first A Class Studio in the basement of the Junction Shop just as the UK sound systems were starting to make waves.

John: When Chris moved his dub-cutter into the basement here we thought "Well, let's get a little studio thing going" and it all keyed in really nicely with the explosion of the British deejays.

John: When Chris moved his dub-cutter into the basement here we thought "Well, let's get a little studio thing going" and it all keyed in really nicely with the explosion of the British deejays.

Chris: It was just really good timing. As we got the four-track studio, the dub-cutting and everything running downstairs, suddenly there was all this talk of UK, London and Birmingham-based deejays that were really ripping it up on sound systems. The big moment for us was when we recorded Johnny Ringo on a few tracks, cut a couple of dubs for him of the rhythms, and then went to hear Ringo and Welton Irie when Gemini played Saxon down at the People's Club. That's when we heard all these deejays that we'd been hearing about: Smiley, Asher and all the rest of them. I used to play guitar with Maxi Priest and Paul Robinson's band Caution and Maxi said to me at a rehearsal "Everyone talks about Philip Levi" because Paul had just produced Mi God, Mi King, "You should check out Smiley and Asher, they're very good as well".

John: The Jamaican deejays were listening to English cassettes. People like Papa San and Lieutenant Stitchie, that's where they were taking their influence from. The deejay thing was great because it suited the limited production abilities we had with a four-track studio. Most deejay music is not about loads of drop ins. A good deejay tune is a performance, so you're trying to encourage that performance from an artist and then maybe patch in a few things, which is kind of instant and it works well. We were in the right place at the right time, more by luck than design. It's how these things work.

John, you've told me before that Fashion's success as a team was based on you bringing your commercial sense from running the shop to temper Chris' skills as a guitarist and studio engineer.

Chris: It was a very important part of it because as John was selling tunes over the counter at a time when I might be working on the studio or cutting dubs or other things, so John had a much clearer view of what's actually selling, or people would be asking for a certain sort of thing. He could spot a trend and say to me "We should make a rhythm like this" or "That rhythm you've got there is good, but we could do this with it" or "There's a certain type of artist that we could put on that rhythm". Whereas because I'm in the thick of it I haven't quite got that overview.

John: I had more of an idea of how the thing should sound so that it would sell. Chris is musical, I know how the business side of it works. The studio time, especially in those days because it was long doing stuff in the studio, I always found a bit boring to be really honest. Taking the vocals and doing the mixes and stuff like that is not so bad because you get a performance, but the going over the harmonies, Chris is more prepared to get that, he's a perfectionist. We complemented each other in that way.

Chris, as well as an engineer you were also a respected reggae journalist. You have a reputation as one of the few reggae writers who actually understands studio craft rather than just as being collectors of records, talking about catalogue numbers and so on.

Chris: I never talk about catalogue numbers. I never see myself as a record collector. I've got records and I like records, but to me a record collector is someone who collects everything by a certain artist or every issue on a label. I don't. I've got records that I like and that's it. But the writing thing came from just liking the music.

John: When we were at school we'd be going out in our lunch hour buying pre-releases and they'd be two or three times the price of a normal release record with a big hole in the middle. You'd go back to school with it and you'd get "You paid a pound for that? You must be a fucking idiot!"

Suddenly there was all this talk of UK, London and Birmingham-based deejays that were really ripping it up on sound systems

Suddenly there was all this talk of UK, London and Birmingham-based deejays that were really ripping it up on sound systems

Chris: Or they'd look at it and go "You paid that amount for a record and they can't even be bothered to put a label on it?"

John: Out of that you kind of feel it needs to be communicated to them just how good it really is. I think it's where Chris' desire to sort of spread it came from. There was no serious writing about reggae at that time. A little bit after Chris Carl Gayle came and Black Music came out and it sort of exploded from there but Chris was doing it from way before. It was good that he spread that word, he found out that there are these other nutters out there that are into this as well.

What was your favourite release on Fashion?

John: That's a good question (laughs). I think my personal favourite is Shan A Shan, Smiley Culture.

Chris: It's difficult for me. Whatever I say to you, two seconds later I'm going to think of something different! I'd say Mood For Love, Carlton and His Shoes; Cool Down Amina, Keith Douglas... Young Rebel, Johnny Clarke. That's not to say that all the records from Fashion are my favourites! (laughs).

John: Some of the Cutty Ranks stuff as well, because it was very immediate with Cutty. When you're talking about getting a performance from someone in the studio, that is the archetype sort of person.

Chris: When he's just demoing a lyric for you, that's frightening enough. When's he's actually giving it 100% behind the mic, that's the full force of the bloke.

John: We had a good rapport with Cutty. And I think out of all the artists that we worked with I personally think that the most impressive in the studio was Frankie Paul. It was just unbelievable that someone was capable of doing that vocally, and as he finished... "Give me another track. Give me another track ". He just put everything down and it was essentially one take.

Chris: You didn't have to give him a lot of direction, might be a couple of little things that you might pick him up on, but he really is very, very good in the studio. He was one of those people who really did seem to have it all in his head.

John: To be really fair, most of the Jamaican artists are pretty easy to work with. The English artists tend to be a bit more precious about what they do and want to go over and over the thing, where a Jamaican artist would be more like "That's it, done". To be fair both me and Chris after a while realised that it was pointless trying to tweak something up because you end up taking all the vibes out of the performance. As they say in Jamaica "Every spoil is a style". Sometimes you take it warts and all and if you listen to a lot of the really best reggae there are, technically, numerous mistakes in it, but it's the overall feel.

When Cutty Ranks is just demoing a lyric for you, that's frightening enough. When's he's actually giving it 100% behind the mic, that's the full force of the bloke

When Cutty Ranks is just demoing a lyric for you, that's frightening enough. When's he's actually giving it 100% behind the mic, that's the full force of the bloke

Chris, as someone who's written about the music, what did you think about the various trends that Fashion catered for? There was roots, lovers, digital ragga, even jungle - on your subsidiary Jungle Fashion.

Chris: Well, we never set out to make any particular part of reggae. We never set out just to make lovers or just to make deejay tunes or just to make roots tunes. So when things come up, like the UK emcee thing came along and we were in the right place at the right time and we liked it, so we made it, you know? Carlton and His Shoes drops into town, certainly he's a big hero to me and I know John likes him as well, we wanted to make a couple of tunes with him. Johnny Clarke's about, let's do a couple of tunes with him. Alton Ellis, my favourite singer of all time, if I've got the opportunity to make tunes with him, I'm going to make tunes with him! So we never had any policy of "We're not going to make this sort of tune or we're not going to make that sort of tune". We're a reggae label, we make reggae tunes, whatever sort of reggae that is. Going back to buying records or whatever, we've always bought deejay tunes, instrumental tunes, singing tunes, dub tunes, roots tunes, whatever.

John: Well, I think really that reggae itself was one thing, it's only later on that it kind of divided into all these sub-genres and people were like "I only listen to roots" or whatever.

If Fashion had continued in the 2000s, do you think you'd have put out newer reggae and dancehall related genres like dubstep or afrobeats?

Chris: I don't particularly like afrobeats. Dubstep to me, what I've heard of it, doesn't particularly touch me. Some of it sounds like jungle, some of it sounds like slowed down dub music. I've said to people "Play me a dubstep tune" and I think "Well, I was doing stuff like that 20 years ago, it's not really that much different". Then they'll play me something else and I'll think "Well, that's something completely different to me, and it's not really me". I mean, when the jungle thing came along that took a little bit of getting used to but I sort of got into it because it could be very musical, very interesting. I ended up quite liking it, and obviously we ended up getting some good jungle deejays to do some remixes and so on and so forth. The reason why I came out of Fashion was because I got to the stage where I was starting to make tunes I didn't like. Once you recognize that in yourself it's time to do something else.

John, has the taking of the Dub Vendor business online given you the chance to do projects like the digital relaunch of Fashion?

John: Personally I don't like to rake over the past too much. I like to go forward. At the moment I'm in a kind of interlude between wherever I go to next. There've been opportunities to reissue the Fashion stuff before but I've never been that motivated even thought we got some big orders for it because I was busy doing other stuff. Don't get me wrong I'm proud of it but I was always felt maybe someone else would come along and do it so I could get on with something else!

Chris: I came out of the studio thing about 12 years ago and I never even played the guitar for about ten years. But then I started doing a couple of sessions for a mate and that started coinciding with starting to get the Fashion stuff together again and because I had such a long break it's been quite refreshing to look at it again.

Will Fashion ever return to new releases?

John: Never say never but me and Chris agree we'd have to find artists that gave us the enthusiasm to produce them. Other people remixing stuff - we're up for that because that interests me because people come to it from a different perspective and different angle. I've got people like Russ from the Disciples who've expressed an interest in working with some of the acapellas. Curtis Lynch and Peckings want to use a couple of rhythms. But we'd like to find new artists. I go to Jamaica quite a lot and when you're there the new music sounds great but when you leave it doesn't seem so relevant. Back in the day the music exported whereas now it's instant music for the people of Jamaica. You hear it in the right environment and it's right but me and Chris wouldn't want to make that.

Smiley was totally credible from the street. He wasn't pretending to be anything or anyone else

Smiley was totally credible from the street. He wasn't pretending to be anything or anyone else

It's one year on since the death of Smiley. What are your memories of working with him?

Chris: I'd say that Cockney Translation was one of my favourite tunes now that's been mentioned as well!

John: Cockney Translation was something that Chris worked on quite a bit with Smiley. The concept of it was Smiley's...

Chris: We worked a lot on the lyrics of that and the performance of it and structure. We heard that when we went to the People's Club that night after voicing Ringo; not only did we hear all those Saxon emcees performing but Smiley did Cockney Translation that night. Me and John went "This is a tune!"

John: Because prior to that we were working on these guys called Laurel & Hardy. To my knowledge they were the first people to come with that uniquely British... not like Judge Dread who's a white bloke who's into reggae, but two young, British-raised, black kids who had the kind of Cockney thing going. But they didn't have the performance levels and the charisma that Smiley had. The difference was that Smiley was totally credible from the street, just the same as Philip Levi, Asher, they were of the street and that was what they did.

Chris: He wasn't pretending to be anything or anyone else.

Read more about this topic

Read comments (1)

| Posted by Guillaume Bougard on 04.08.2012 | |

| Great interview of two absolutely essential players in the history of Reggae, not only in the UK scene but overall. | |

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z