Articles about reggae music, reviews, interviews, reports and more...

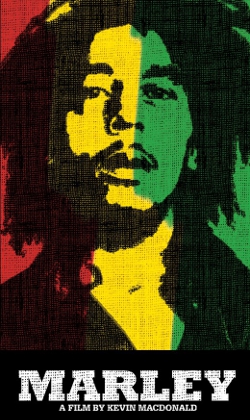

Marley Movie

Marley Movie

Kevin McDonald has done a fine job of celebrating Marley's legacy on the big screen.

Kevin McDonald’s feature-length Bob Marley bio-pic has a lot going for it. A sensitively rendered exploration of the life and work of Jamaica’s most famous son, it presents the public with a lot of different viewpoints of the man, mostly rendered through first-hand interviews conducted with those that knew him best. There is some appealing archive footage as well (though some ancient material suffers from poor visual and audio quality, having degraded over time), and there are excellently executed visuals, some shot from above, which remind just how beautiful—and dangerous—much of Jamaica actually is. Though a few errors and questionable assertions form niggling annoyances, it is a fine film overall that is basically required viewing for Marley fans and anyone interested in Jamaican music and culture.

Kevin McDonald’s feature-length Bob Marley bio-pic has a lot going for it. A sensitively rendered exploration of the life and work of Jamaica’s most famous son, it presents the public with a lot of different viewpoints of the man, mostly rendered through first-hand interviews conducted with those that knew him best. There is some appealing archive footage as well (though some ancient material suffers from poor visual and audio quality, having degraded over time), and there are excellently executed visuals, some shot from above, which remind just how beautiful—and dangerous—much of Jamaica actually is. Though a few errors and questionable assertions form niggling annoyances, it is a fine film overall that is basically required viewing for Marley fans and anyone interested in Jamaican music and culture.

The film begins at ‘the door of no return’ in the West African slave fort from which countless souls were shipped across the Atlantic, the ancestors of Marley’s mother’s side of the family among them. Soon we are flying over Jamaica’s incredibly dense tropical wilderness, landing in Nine Miles, St Ann, to check the circumstances of Marley’s birth in 1945; the facts are that his teenaged black mother was made pregnant by a womanising, self-mythologizing white man already in his mid-60s. The film’s first false move comes up here: a supposed cousin of Bob Marley tells us that his father, Norval Marley, was a white man ‘from England’, when he was in fact a mixed-race Jamaican, and surely the on-screen narrative, provided by subtitles, should have corrected this mistake. Next, a nephew of Norval tells us that he fought in some war overseas, but the narration claims there is ‘no evidence to support the assertion’—well, OK, but what else do we actually know about Norval Marley? Not much, apparently, because the film never really tells us anything more about him. We are later introduced to Bob Marley’s half-sister, who met his wife Rita while working at a local dry cleaners; her testimony is fascinating, and says a lot about race and class in Jamaica, but then here comes another clunker: former manager and friend Alan ‘Skill’ Cole suggests that the song ‘Cornerstone’ is about Bob’s rejection by his father’s side of the family, and the song is played to the half-sister, who never heard it before, as a statement of gravity, but anyone familiar with the song will surely know that it is delivered as a boastful ballad to a scorned lover. So some of Marley’s assertions are off the mark, but these are minor quibbles, compared to the many positive aspects.

The meat of the film is served up in fantastic quotes from Bunny Wailer, Rita Marley, and art director Neville Garrick, with other fascinating cameos by producer/manager Danny Sims, bassist Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett, singer Marcia Griffiths, guitarist Junior Marvin, singer Dudley Sibley and Lloyd ‘Bread’ McDonald of the Wailing Souls. The sections of archive interview material with Bob Marley are also well chosen, as is the brief moment when Peter Tosh describes why he left the Wailers. Live footage reminds how brilliant the Wailers always were on stage (and how lacking most contemporary artists are today). The film generally does a good job of showing Marley’s slow rise to fame, and the terrible responsibilities that came with it, such as the attempt on Marley’s life in 1976 that forced him into a long exile, and the chaos of his live appearances before heads of state in Zimbabwe and Gabon. His commitment to Rastafari is touched upon, but not made a central focus.

One of the things I really appreciated about the film were the portions with Marley’s son Ziggy and daughter Cedella, who both mention some aspects of his deficient parenting. Cedella speaks disparagingly of his infidelities, and both say his competitiveness extended even to his relations with his kids. It points to certain failings of this incomparable icon, which help to remind that he was human, after all, despite his extraordinary qualities.

Throughout it all, we get the sense that Marley was always aware of the bigger picture, and saw his music as a vehicle to better mankind, rather than a spaceship for an ego trip. Chris Blackwell comes across as well-meaning and committed to getting Marley and the Wailers to the widest possible audience, though his assertion that Marley would probably still be alive today had he not ‘forgotten’ to insist that Marley obtain regular medical check-ups following the initial surgery to his cancerous toe, seems mightily strange when pondered in retrospect (though I do not doubt the veracity of his statement). The death and funeral of Marley are handled sensitively, and I liked that the film ended with images of children in different parts of the world singing the songs of Marley, as it reminds how his music has struck something of a universal chord.

Considering that the film draws together entities that are not necessarily on speaking terms, and since several high-calibre directors, including Martin Scorcese and Jonathan Demme, bailed out years ago, Kevin McDonald has done a fine job of celebrating Marley’s legacy on the big screen. It may not be perfect, but you are guaranteed to feel good when you are exiting the cinema, and you will certainly learn more about the life and times of Bob Marley during the two and a half hours of the film’s duration.

Read more about this topic

Comments actually desactivated due to too much spams

Browse by categories

Recommended Articles

Latest articles

Recently addedView all

© 2007-2026 United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. Read about copyright

Terms of use | About us | Contact us | Authors | Newsletter | A-Z